© USGS

San Andreas, CA - Hundreds of basins carved into a football field-sized granite ledge in a remote Sierra Nevada wilderness are the remains of what may be the oldest manufacturing operation in North America, according to a U.S. Geological Survey study whose results were released in December.

The researchers concluded that the more than 350 basins three to four feet in diameter were used to evaporate salt from the briny flow of a nearby spring.

"The water was carried to the individual basins, probably in water-tight baskets, where it dried in the summer heat, leaving a salt residue on the basin floor," said Jim Moore, USGS geologist and co-author of the report.

"Such a large enterprise produced far more salt than was needed by the local tribe for cooking, preserving food, and attracting animals for hunting, and they had a large surplus of the valuable item left over for trade with other tribes."

Moore and other researchers estimate the site could have produced about 2.5 tons of salt per year.

At least some scholars are skeptical that the site could be the oldest or largest salt production operation on the continent.

"There certainly were areas in North America where people were producing salt on a larger scale than that," said Michael Delacourte, an associate professor of anthropology at California State University, Sacramento.

A cave in Kentucky, for example, was worked by prehistoric miners.

"Sometimes miles into the passages. And that's been going on for thousands of years," Delacourte said. Remains of ancient torches and human remains made it possible to date that mining, he said.

At other sites on the continent, ancient people sometimes used earthenware evaporating pots to produce salt from springs, Delacourte said.

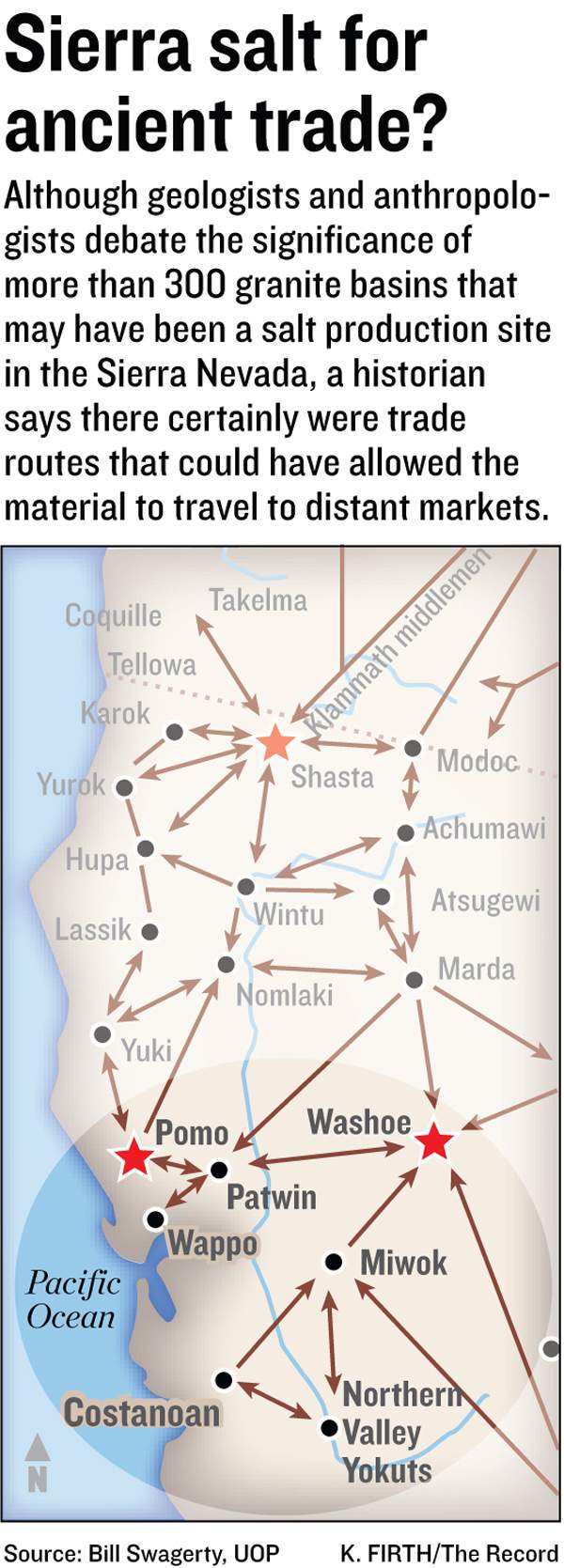

Experts on ancient trade routes say it is possible salt from the Sierra site was traded to people hundreds of miles away.

"Salt is an old trade item in aboriginal North America, so it doesn't surprise me at all," said Bill Swagerty, a professor of history and director of the John Muir Center for Environmental Studies at University of the Pacific.

According to the USGS report, "This site is the most impressive prehistoric saltworks yet discovered in North America."

Delacourte disputes that and also says he's skeptical that it could be the oldest. As with other rock artifacts, it will be difficult or impossible to date the stone basins.

At the same time, Delacourte said that salt would have been a valuable commodity at the Sierra location.

"All people everywhere want salt," Delacourte said. "The High Sierra and much of the western slope of the Sierra are salt deficient."

The geologists say it wasn't easy to convert the local granite bedrock into a salt-production factory.

"Fire was probably used to heat the rock, reducing its strength and making it easier to grind," said Mike Diggles, a USGS geologist and co-author of the report. "To deepen the basins just one centimeter, they had to build and maintain a hot fire on the rock, let it burn out, and then pound the bedrock with stone tools."

The creators of the salt works had to repeat this process about 100 times to carve a basin three feet deep into the stone. It would have taken several workers nearly a year to make just one basin, the report said.

The rows of evaporation basins and their consistent size are striking. And there's well-known history of salt production and trade among American Indians.

Yet there's been controversy over whether the stone basins are natural since European-descended scientists first saw the evaporation ponds in the late 1800s.

Henry W. Turner, who studied the area in the 1890s while working on a U.S. Geological Survey geological atlas, concluded it was "most likely" that the natural flow of water or the grinding force of a glacier created the basins. He came to that conclusion despite that fact that a man who had lived with American Indians in the area told him that they had been made for the purpose of creating salt.

The controversy is far from resolved. The basins' overhanging lips lead Delacourte to question whether they are human-made at all. "It is almost impossible to produce those by hand," Delacourte said. The water or glacial forces cited by Turner seem more likely to Delacourte, who also said he has not visited the site himself.

Moore stands by his science. He said he even did experiments, heating similar rock with fire and pounding it to determine it was possible to carve the basins six times more quickly than would be possible without heat. And he said the location of the overhanging lips on many basins makes sense given how the basins' creators would have had to work on the sloping ledge.

"I think we have pretty compelling data," Moore said. "We recorded those overhanging lips very carefully."

The Geological Survey report does not reveal the exact location of the saltworks. Federal law requires that as a measure intended to avoid attracting visitors who might damage archeological sites. The site's remote location and steep topography make getting there difficult, and as such visitors are relatively few.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter