More than 700 genetic syndromes affect facial traits, but some are difficult to spot because few cases exist.

|

| The visuals derived from his software show that affected children have narrower temples; and a more upturned nose and fuller lips. |

Now new software that compares an individual's face with a bank of 3D images of people with known conditions is aiding diagnosis.

The technology, presented at the BA Festival of Science in York, had a 90% success rate, the scientists said.

Peter Hammond, a computer scientist at the UCL Institute for Child Health in London who carried out the research, explained: "There are many conditions where the face can have unusual features arising from alterations in the genes."

'Average face'

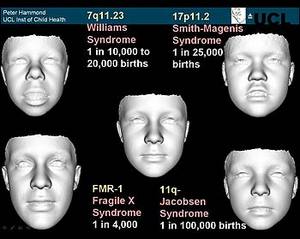

While individuals with Down's syndrome can be easily recognised, there are more than 700 known genetic conditions that can alter how a person looks.

For example, people who have Williams syndrome, which occurs in between one in 10,000-20,000 births, have a short, upturned nose, a full mouth and a small jaw.

Individuals with Smith-Magenis syndrome, which occurs in one in 25,000 births, have a nose with a very flat bridge and a lifted lip. While those with Fragile X syndrome, which has an incidence of about one in 4,000, have long, narrow faces and large or protruding ears.

For some genetic conditions, facial differences can be very subtle and cases can be rare, making initial diagnosis extremely difficult.

To help, Professor Hammond has collected 3D images of children with known problem and has created software that combines the images to create an "average face" of a child with different genetic conditions.

In the same way, he has also built up the average face of a child with no known genetic disorder for comparison.

Each composite image is made up of between 30 to 150 images.

Faster diagnosis

Professor Hammond said: "When we have a child with an unknown condition, we take a 3D picture of their face and we have developed techniques that allow us to compare their face with these averages.

"And the one that is the most similar is the prime target as the condition that might explain their unusual facial features.

"Then the geneticists can do the more appropriate genetic testing, if such a test exists, to further confirm this."

So far, the technique is currently being applied to more than 30 conditions with an average success rate of 90% and Professor Hammond is collecting more images to encompass even more genetic conditions.

Using the software would speed up diagnosis and reduce the number of genetic tests a child might need, he said.

Professor Hammond is currently using the technology at his hospital in London, but would like it to be rolled out across the UK.

This would involve more 3D cameras in hospitals or technology that could convert 2D images to 3D.

In the future, Professor Hammond is looking to compile enough data to build average images of genetic diseases for different sexes and ethnicities.

In work soon to be published, Professor Hammond has also used the software to examine the facial characteristics of people with autism spectrum disorder and has identified unusual facial asymmetry in children with the condition.

These children are more likely to have a slight protrusion of the right temple, possibly reflecting a larger area of the brain known as the right frontal pole.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter