The flighty creature was first spotted a couple weeks earlier just outside of Harrisonburg foraging in some thick nestle. Scaggs, 57, quietly scoured these secluded areas in hopes of catching a glimpse of a yellow wing, finally tracking it on a honeysuckle bush. The silky gray hood and striking white arcs around its eye identified the winged animal as the one he had been hunting. He slowly lifted the scope to his eyes for a clear, swift shot.

Click.

A perfect picture of MacGillivray's warbler, a bird thousands of miles away from the warm climate it flees to this time of year.

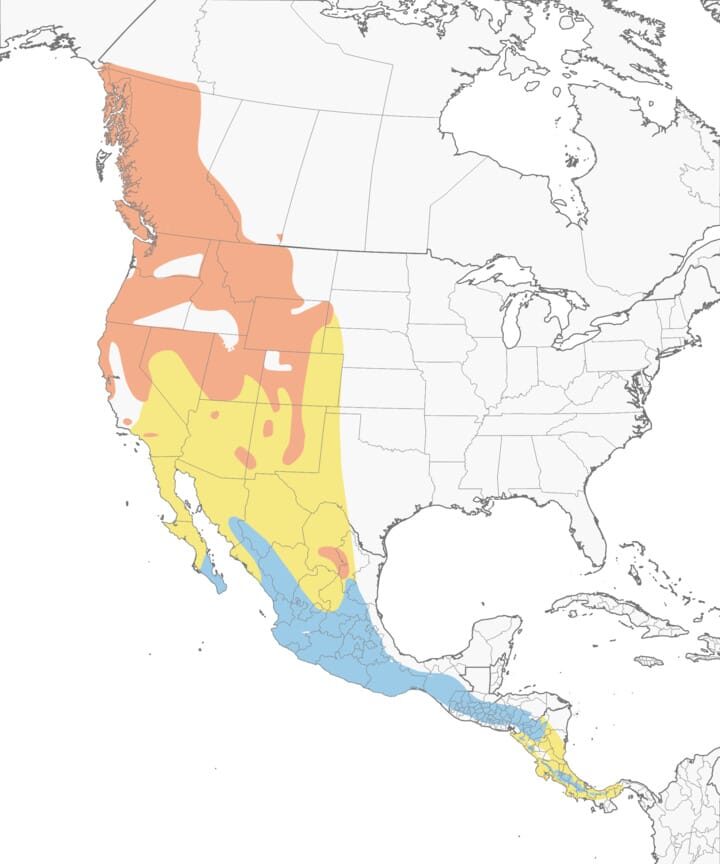

MacGillivray's warbler shouldn't be in America, much less Virginia. The bird is native to the West Coast, its breeding grounds running from California up into the northernmost reaches of British Columbia. In the winter months, it travels as far south as Colombia and Venezuela to escape the cold. So what is this lone female warbler doing in the Shenandoah Valley?

"Oftentimes when you have birds that show in locations where you don't expect them, there are a couple of possibilities," Scaggs explained. "Navigation could be off potentially. They could have been going where kin are going to winter and took a left turn along the way. Or it could be more of a situation where the bird intentionally came further east instead of south, there is some evidence that that is the case with certain western species. Not because something's wrong, that's just where the bird decided to go."

News of the warbler flew through the state's birding community. Garland Kitts, a 65-year- old retiree from Roanoke whose passion for photography led him to the world of birdwatching in the past five or so years, received an alert in early December from an app notifying birders of rare bird sightings. He also is tuned into the online database called eBird that is full of bird observations, distributions and a plethora of other feathery information run by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Kitts made the two-hour trek up to Lake Shenandoah in the beginning of December with a fellow birder after being notified of the MacGillivray's appearance. They were not the first to respond to the call and came across several dozen bird enthusiasts who located the bird in a patch of honeysuckle where she was foraging for something to eat. The female fowl entertained her fans for some time, allowing several pictures to be taken, before she flew over into some thick nestles where her paparazzi were unable to follow.

"It was very fortunate that we were able to find it pretty fast," said Kitts, who credits a World War II photographer for developing his love for photography.

Whether navigationally impaired or a brave explorer, the bird was far from home. However, MacGillivray's warbler does have some cousins to visit in the area. The mourning warbler's breeding grounds stretch across the Midwest to the western part of Virginia and to the untrained eye can be indistinguishable to its Western relative.

"The only difference is that MacGillivray's have the white arcs above and below the eye," said Scaggs. "The mourning lacks the eye ring." Though he did not visit Lake Shenandoah searching for MacGillivray's warbler until Dec. 21 on Kitt's second trip, Scaggs had previous experience with the bird when he was living in the Midwest on the plains of Colorado, the easternmost edge of its range usually.

On Dec. 21 when Kitts and Scaggs traveled to Lake Shenandoah for Scaggs' first search for the rare bird and Kitts' second, they braved the cold and recorded the 30 mallards and 26 geese they saw on eBird before their patience paid off, sighting of the star of show.

While she seems to have made herself comfortable in the area for the past few weeks, the impending weather may force the bird to rethink her decision about spending the winter months in palm trees.

"Birds are fairly well adapted to deal with the cold, [but] finding food is the key and snow can make this more difficult," said Scaggs. "Warblers primarily feed on insects but some will utilize berries to supplement their diet especially during winter. Hopefully it will do okay."

SOTT falls short on edgy science and seems more mainstream as time goes.

Maybe more gender dysphoric...