Does Bangladesh provide a useful template for Indian intervention in Balochistan?

The basic outlines of the Bangladesh story are pretty simple.

In 1970, Pakistan ditched a program to maintain parity between (less populous but politically, militarily, and economically dominant) West Pakistan and East Pakistan and switched to a plain-vanilla direct election model for the national parliament. The Bengali-based and autonomy-leaning Awami League unexpectedly pretty much swept the East Pakistan races and was poised to control parliament and choose the prime minister of all of Pakistan.

This did not sit well with the military and civilian elites of West Pakistan, which tried to crabwalk out of the deal. In late March 1971, after a few months of negotiations and increasing polarization, West Pakistan opted for a military solution, suspending civilian rule and sending in the army to cow, disarm, and massacre the opposition as circumstances dictated (or permitted).

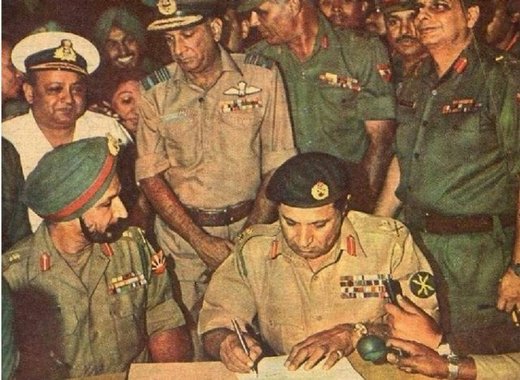

The East [Pakistan] situation spiraled into a non-stop horror show of dirty war, insurrection, and communal violence, until India brought things to a close in December 1971 with a massive invasion, the surrender of the Pakistan army, and the establishment of [Bangladesh].

That's the simple part. Anything beyond a bare narrative of events is, as they say, contested terrain.

The prevalent narrative is that of the winning side, understandably. Bengali nationalists describe a genocide, with the Pakistan army and its affiliated paramilitaries butchering and raping their way across the country until the people of Bangladesh, with the assistance of the Indian army, put a stop to it by winning a war of national liberation.

The official Bangladesh figure is 3 million killed, and any attempt to tinker with the seven-figure death toll that bestows the coveted "victim of genocide" credential is treated with contempt and anger.

Contempt is reserved for the Pakistan government, which convened a commission to explain how half the country got lost and came up with a ludicrous number of 28,000 Bengalis killed.

Anger and condemnation as a holocaust denier for third parties who question the undocumented figure of three million and place the death toll at perhaps 300,000, in line with what the CIA was estimating at the time, a huge number but still one tenth of the canonical figure.

What is even more fraught is the question of who died and who did the killing.

Thanks to the work of Sarmila Bose, recorded in her book Dead Reckoning, an answer to both questions presents itself: pretty much everybody.

The Pakistan army apparently operated like the French in Algeria, conducting a campaign of state terror against a province in rebellion, arresting the ANP leadership as a bargaining chip, death-squading intelligentsia they didn't arrest, brutalizing and intimidating the countryside in an effort to deny the insurgents access to the active support and assistance of a sympathetic citizenry.

Adjuncts to Pakistan's dominion over the East—and the source of recruits for the Razakar militias—were the "Biharis", the name given to Muslims who had migrated to East Pakistan from the eastern provinces of India, mainly but not exclusively Bihar, and spoke Urdu, not the predominant Bengali language.

Unsurprisingly, Biharis were subjected to reprisal massacres by Bengalis after the Pakistan army surrender. Post-conflict, many fled to refugee camps set up by the Red Cross and, remarkably, over 100,000 still live in those camps 35 years later, slowly trading their dreams of repatriation to Pakistan for assimilation into Bangladesh as second-class citizens.

But it appears that the primary, hidden victims of the violence attending the birth of Bangladesh were Hindus.

While suppressing the Awami League and the Bengali political movement, the Pakistan Army apparently conducted a program of ethnic cleansing, inciting through violence and the threat of violence a massive migration of East Pakistan's Hindu population—which it considered at best passively disloyal and at worst a fifth column—to flee to India. The gigantic flow of refugees—up to 10 million, at least 80% of whom were Hindu, representing half of East Pakistan's total Hindu population—created a humanitarian and political headache for India, one that the late prime minister Indira Gandhi framed as an intolerable cross-border crisis fomented by Pakistan that justified the subsequent invasion.

As Gary Bass recounts in his book The Blood Telegram, horrified reports from the U.S. Consulate in Dhaka also described an extensive pogrom of the Hindu community, with wholesale destruction of Hindu neighborhoods (yellow 'H's painted on doorways identified the targeted households), systematic killing of Hindu intelligentsia, and summary executions a.k.a. murder of villagers who were commanded to "lift their lunghi" i.e. hike up their sarong-like lower garments to expose themselves and, if found not to be circumcised Muslims, shot on the spot.

At the time, advisors in the Indian government believed that the Pakistan military was cleansing East Pakistan of its Hindus so that the total population of East Pakistan would decrease to a point where West Pakistan was more populous and its MPs would hold an absolute majority in parliament.

Hindus tended to support the avowedly secular Awami League (AL), so the pogrom could conceivably have been part of a scheme to weaken the AL and push East Pakistan's politics into an overtly Islamist channel favoring the pro-unity Muslim League, the secular Awami League's rival in the East.

Pakistan desperately avoids any [implication] it engaged in any ethnic pogroms against Hindus at all in the East, and it is unlikely to confess its government and military went into East Pakistan with a plan to commit crimes against humanity for the sordid purpose of jiggering with local demography and the vote bank.

However, I'm inclined toward this narrative for the simple reason that in 1971 West Pakistan's military and civilian elites seemed to be moving toward a consensus that holding on to East Pakistan by conventional political and military means was extremely unlikely. Perhaps some generals thought that, with the East wing basically lost, radically reshaping East Pakistan society and politics with a new mini-Partition under India's nose was a long shot worth trying.

Well, if that was the plan, it didn't work.

Interestingly, the India government shares Pakistan's unwillingness to focus on the anti-Hindu ethnic cleansing at the heart of the Bangladesh horror.

According to Bass's account, the Gandhi government suppressed reporting of the anti-Hindu pogrom to dodge political pressure from the hyper-nationalist Bharatiya Jana Sangh (BJS) party then in opposition, and to forestall an explosion of retaliatory communal violence against Muslims in India.

Perhaps another reason is that, if the anti-Hindu pogrom element was emphasized, it would be regarded as part of the bloody unfinished business of the 1947 Partition—and India might be expected to welcome the Hindus of East Pakistan into its bosom (and its politically and economically shaky eastern states) instead of starting a war to return them to a newly liberated homeland of Bangladesh.

Indeed, the Indian government was resolute in disclaiming any national obligation to receive the refugees, hurrying them back at astounding speed—at one point, over 200,000 more or less enthusiastic Hindu refugees were delivered from camps in India to the new nation of Bangladesh per day—within a few weeks after Pakistan forces surrendered in Dhaka.

Perhaps more were less enthusiastic. Judging by accounts in Sarmila Bose's book, during the 1971 struggle, embattled Hindus of East Pakistan were harassed and persecuted both by Pakistan's army and cruel and opportunistic Muslim neighbors of all backgrounds, Bengali as well as Bihari.

In addition, the rulers of Bangladesh have showed little apparent interest in diluting their national moral claims by fully acknowledging the important role of Hindu victims in the holocaust.

Embarrassingly, Hindus have not done particularly well in Bangladesh, especially after its rulers abandoned the Awami League secular/socialist vision and veered into political Islam soon after 1971. At partition, Hindus constituted perhaps 22% of the population of East Pakistan, decreasing to 14% after the horrors of 1971. Today, after decades of Islamist harassment, some of it officially condoned, Hindus account for around 8.5% of Bangladesh's total population.

With this perspective, East Pakistan does not offer a particularly promising precedent for Indian action on Balochistan.

Obvious parallels are between East Pakistan and Balochistan as provinces of the British Raj lost at partition that are homelands to ethnically distinct Muslim populations alienated from the Punjabi elite that rules out of Islamabad.

Indira Gandhi's India respected the sovereignty of newly established and largely Muslim Bangladesh and declined to try and incorporate it into the Indian polity; Balochi independence activists would expect similar hands-off treatment in any aftermath.

However, in important respects, the Bangladesh playbook does not apply to Balochistan.

There are not many Baloch, maybe 8 million in a Pakistan nation of 182 million, and the government has access to positive demographic tools that were unavailable in East Pakistan. Balochi demographic and political predominance, as well as their political unity and capacity to organize resistance to the central government, are being eroded by a managed influx of immigration in a matter familiar to students of PRC policies in Tibet and Xinjiang, instead of via pogroms and ethnic cleansing.

Officially, speakers of the two main local dialects, Baloch and Brahui, account for 55% of Balochistan's population of 14 million. That's actually down 10% from the 2011 estimate. Aggrieved Balochi advocates accuse the central government conniving with local Pashtun parties to resettle Pashtun Afghan refugees in Balochistan with the goal of creating a "fifty-fifty" province in which Pashtuns enjoy parity and ethnic Baloch political power is neutered.

And if Pakistan's political schemes for Balochistan do collapse into a large-scale insurgency, Baloch refugees will be streaming across the border not into India but into the unwelcoming arms of Iran, which has restive Baloch of its own and no desire to encourage them.

Balochistan, unlike Bangladesh, is on (Pakistan) Punjab's doorstep and in easy reach of Pakistan's military; this time India is further away, across Sindh and unable to provide direct havens for militants.

And finally, India hawks cite that the PRC sat out the East Pakistan imbroglio, and profess confidence that a combination of Indian deterrents and inducements will persuade China to throw Pakistan under the bus if and when the Balochistan situation escalates. But 2016 is not 1971, Balochistan is not Bangladesh, and the PRC sees a vital national interest and critical strategic counter to India in a whole and happy Pakistan with the CPEC corridor operating securely and successfully through Balochistan to its southern terminus at Gwadar.

That is not to say that Prime Minister Modi is without recourse and options if he wishes to destabilize Balochistan to the benefit of the independence movement. Beyond India's Research and Analysis Wing's mischief, Modi and Afghanistan's President Ghani seem to share hopes of pincering Pakistan to the west and east and giving it more than it can handle. If this involves infiltrating assets into the Pashtun-heavy northwestern areas of Balochistan bordering Afghanistan, interesting problems could be created.

However, the conditions for a direct Indian military intervention in the Balochistan independence struggle do not appear to exist. Balochistan may suffer the joys and sorrows of a liberation struggle. But they are likely to be unique to Balochistan and not a replay of the experiences of Bangladesh in 1971.

Peter Lee runs the China Matters blog. He writes on the intersection of US policy with Asian and world affairs.

Comment: Further reading: