Under state law RCW 27.44.040, anyone who knowingly removes a cairn or grave of any Native American is guilty of a class "C" felony. And under another section of the same code, RCW 27.44.050, a plaintiff may recover punitive damages upon proof that the violation was willful.

Brian Cladoosby, chairman of the Swinomish Tribal Senate, confirmed this week that the tribe has not opened litigation against the city, despite clear evidence that Oak Harbor officials were aware of a possible burial site adjacent to SE Pioneer Way.

"It's pretty obvious the city ignored (the state's) recommendation to have an archaeologist on site," he said.

Shortly after bones were discovered under SE Pioneer Way last month, state Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation officials released documents that showed city officials knew a site was nearby. The state agency warned that an expert should be on hand to observe construction but none was ever hired.

It's becoming increasingly clear that people have been finding human remains downtown for years. According to a timeline released by the Swinomish Tribal Community, there are reports of bones being found by pioneers as early as the 1850s.

Additional first-hand accounts of "an unearthed Indian grave in the vicinity of 450 SE Pioneer Way" were received in the 1920s and an archaeologist, T.T. Waterman, documents a Lower Skagit settlement in the area, the timeline said.

It goes on to claim that the Navy contacted the tribe in 1940s and arranged for remains found in the area to be removed and buried elsewhere. In the 1950s, University of Washington archaeologist Alan Bryan formally recorded a location nearby as an archaeological site with the state.

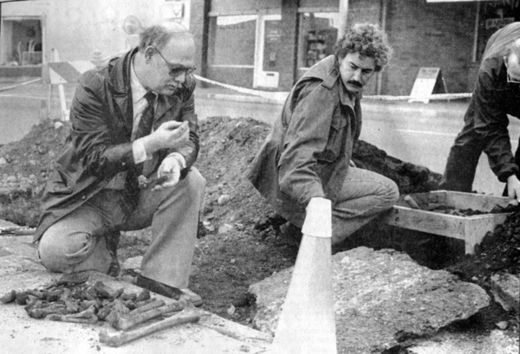

Finally, in 1983 a front page story in the Whidbey News-Times reports bones unearthed in front of the Cathay Palace. The restaurant was located in nearly the exact same location on SE Pioneer Way as the discovery this past week.

The article states that Oak Harbor police officers recovered "about 15 pounds of bones" from a hole dug in the street to service a gas line. Then-Assistant Police Chief Pete Gaalema was quoted as saying that the remains were probably Native American due to the presence of shell midden.

While more information could be derived by scientists with the right equipment, the site had been greatly disturbed and that would make the effort much difficult, he said.

"That's what happens when you discover a burial grounds with a backhoe," Gaalema told the News-Times in 1983.

While the historic preservation office's documents alone make it clear that city officials knew a site was in the area, what's not clear is whether that would be enough to stand up in court.

State law specifies the action must be "willful." If it were "accidental or inadvertent," and "reasonable efforts were made to preserve the remains," it could provide a complete defense.

Cladoosby and other tribal leaders came to Oak Harbor this week and spent several hours meeting with senior city officials. Mayor Jim Slowik said he spent the first 20 minutes in private with the attending tribal members offering his personal apologies for the mishap.

"I promised him that, from this point forward, the city would do the right thing," Slowik said.

Although the tribe is keeping all its legal avenues open, Cladoosby said the city has been cooperating fully with the tribes and that there are no immediate plans for litigation. That's contingent on Oak Harbor's continued willingness to accommodate the tribe's wishes, however.

"We did let them know that the nuclear option would be court if we felt they weren't cooperating," Cladoosby said.

It's still unknown how the remains will be handled. Normally, the preferred option is to just cover them back up. In this case, it's more complicated because a lot of bones were moved to a dump site on Pit Road.

Cladoosby also said the blame isn't solely on Oak Harbor. The historic preservation office should have notified the tribes that the city was planning a project around a known site when they warned Oak Harbor to have an archaeologist on hand.

According to Cladoosby, the tribe's wish is to "turn this negative into a positive" and that the end goal is to see the road project completed. However, ensuring the site is investigated properly and that the remains are handled appropriately is a process that will be both time consuming and costly, he said.

"If they had just told us right away, we'd be in a lot better position than we are now," he said.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter