A man with an unusually tiny brain managed to live an entirely normal life despite his condition, caused by a fluid buildup in his skull, French researchers reported on Thursday.

Scans of the 44-year-old man's brain showed that a huge fluid-filled chamber called a ventricle took up most of the room in his skull, leaving little more than a thin sheet of actual brain tissue.

"He was a married father of two children, and worked as a civil servant," Dr. Lionel Feuillet and colleagues at the Universite de la Mediterranee in Marseille wrote in a letter to the Lancet medical journal.

The man went to a hospital after he had mild weakness in his left leg. When Feuillet's staff took his medical history, they learned he had had a shunt inserted into his head to drain away hydrocephalus -- water on the brain -- as an infant.

The shunt was removed when he was 14.

|

| ©REUTERS/Lionel Feuillet, Jean Pelletier and Henry Dufour-Universite de la Mediterranee/Handout

|

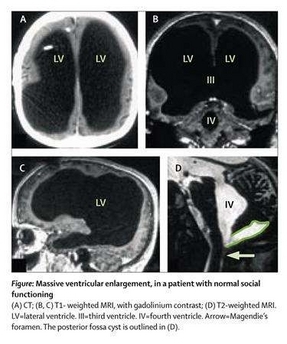

| Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scans of a 44-year-old man's brain show a huge fluid-filled chamber called a ventricle taking up most of the room in his skull, leaving little more than a thin sheet of actual brain tissue, in this handout image released by French researchers July 19, 2007. The man with the unusually tiny brain has managed to live an entirely normal life as a married civil servant with two children despite his condition, according to the researchers.

|

So the researchers did a computed tomography (CT) scan and another type of scan called magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). They were astonished to see "massive enlargement" of the lateral ventricles -- usually tiny chambers that hold the cerebrospinal fluid that cushions the brain.

Intelligence tests showed the man had an IQ of 75, below the average score of 100 but not considered mentally retarded or disabled, either.

"What I find amazing to this day is how the brain can deal with something which you think should not be compatible with life," commented Dr. Max Muenke, a paediatric brain defect specialist at the National Human Genome Research Institute.

"If something happens very slowly over quite some time, maybe over decades, the different parts of the brain take up functions that would normally be done by the part that is pushed to the side," added Muenke, who was not involved in the case.

I guess this just goes to show that it doesn't take a lot of brains to work for the government.