© CHRISTIAN WATSON

Since my days in medical school, I have had a fascination with the kernel insight behind vaccination: that one could successfully expose a person to an attenuated version of a microbe that would prepare and protect them for a potentially lethal encounter with the actual microbe. I marveled at how it tutors an immune system that, like the brain, has memory and a kind of intelligence, and even something akin to "foresight." But I loved it for a broader reason too. At times modern science and modern medicine seem based on a fantasy that imagines the role of medicine is to conquer nature, as though we can wage a war against all microbes with "antimicrobials" to create a world where we will no longer suffer from infectious disease. Vaccination is not based on that sterile vision but its opposite; it works

with our educable immune system, which evolved millions of years ago to deal with the fact that we must always coexist with microbes; it helps us to use our own resources to protect ourselves. Doing so is in accord with the essential insight of Hippocrates, who understood that the major part of healing comes from within, that it is best to work

with nature and not against it.

And yet, ever since they were made available, vaccines have been controversial, and it has almost always been difficult to have a nonemotionally charged discussion about them.

One reason is that in humans (and other animals), any infection can trigger an archaic brain circuit in most of us called the behavioral immune system (BIS). It's a circuit that is triggered when we sense we may be near a

potential carrier of disease,

causing disgust, fear, and avoidance. It is involuntary, and not easy to shut off once it's been turned on.

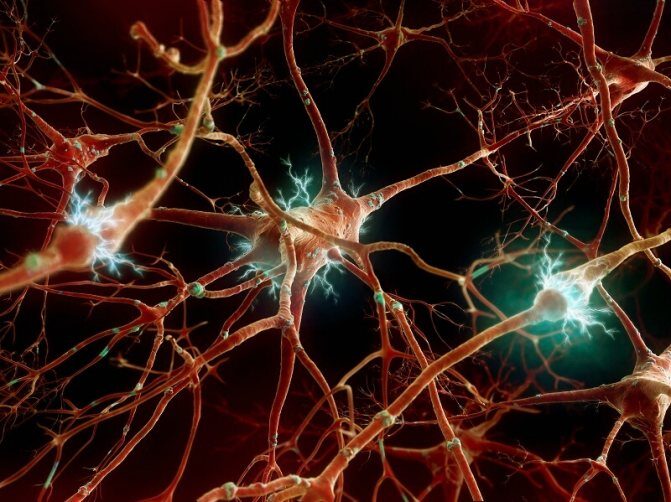

The BIS is best understood in contrast to the regular immune system. The "regular immune system" consists of antibodies and T-cells and so on, and it evolved to protect us

once a problematic microbe gets inside us. The BIS is different; it evolved to prevent us

from getting infected in the first place, by making us hypersensitive to hygiene, hints of disease in other people,

even signs that they are from another tribe — since, in ancient times, encounters with different tribes could wipe out one's own tribe with an infectious disease they carried. Often the "foreign" tribe had its own long history of exposure to pathogens, some of which it still carried, but to which it had developed immunity in some way. Members of the tribe were themselves healthy, but dangerous to others. And so we developed a system whereby anything or anyone that seems like it might bear significant illness can trigger an ancient brain circuit of fear, disgust, and avoidance.

Comment: For more insightful analysis from the author, see:

- The Psychorium: A needed new analytical tool in the study of pathocracy

- Is the Surplus Elite's class coup possible without degenerating into pathocracy?

Also check out SOTT radio's: MindMatters: The Managerial Revolution and the Circulation of the Elites