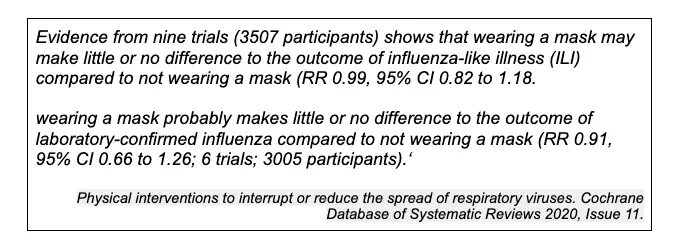

Some of us started reviewing the evidence of the effects of physical interventions on the spread of viral respiratory infection two decades ago. The

Cochrane review, now in its fourth update, concludes there is still uncertainty about the effects of face masks.

"Physical interventions" include hand washing, distancing, disinfection and barriers, including all types of masks.

SARS-CoV-2 had not been identified when we did the last update (published in November 2020), so we reviewed what physical interventions did to affect the spread of influenza and influenza-like illness. Most identify these two as "Flu". We have already

shown the lack of knowledge that accompanies this microbiological simplification.

Influenza-like illness is a syndrome made up of a constellation of signs and symptoms: fever, cough, runny nose, malaise, fatigue and so on, with which everyone is familiar. It is a multiagent syndrome caused by scores of known viruses (including seasonal coronaviruses) and many more which are unknown; Influenza (which cannot be distinguished clinically from the rest of influenza-like) illness is caused by two specific viruses (Influenza A and B) that can be diagnosed only after a laboratory test.

Before the pandemic, clinical trials in widely different settings and using different types of masks show no clear-cut effect against Influenza-like illnesses and influenza.

Although trials of medical/surgical masks are logistically challenging,

the message is unequivocal: they do not appear to do much. Their effect on the broader community is unknown. These are broadly the same conclusions of the only two available randomised trials of masks conducted on Covid-19.

In previous versions of the Cochrane review, we included observational studies; some carried out after the 2003 SARs-1 epidemic. These lower quality studies showed an apparent effect, which higher quality studies failed to confirm. This is not an unusual situation that we find ourselves in Evidence-based medicine.

Who should you believe? Those that espouse low-quality evidence and its certainties or those rely on higher quality trial evidence - as we did in version 4 - with its inherent message of uncertainty.

The bottom line for evidence is to address the uncertainty. Throughout this pandemic, many seem to have had difficulty coping with uncertainties; they have jumped on any evidence that provides an element of certainty - at the time, this can feel reassuring. However, we have a tried and tested way of dealing with uncertainty in science: randomised trials.

It is a terrible indictment of the current leadership that no such trials have been planned or done, those which are on the stocks have had problems with funding and recruiting enough participants, and some researchers have been subjected to malicious personal attacks. Any government "following the science" should have sponsored a range of trials testing different types and mixes of physical interventions in various populations and settings. They should have mandated genuine scientific efforts to diminish uncertainty. But politics, social media and the fatal attraction of spurious certainty underpinned by low-quality studies seem too much to overcome.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter