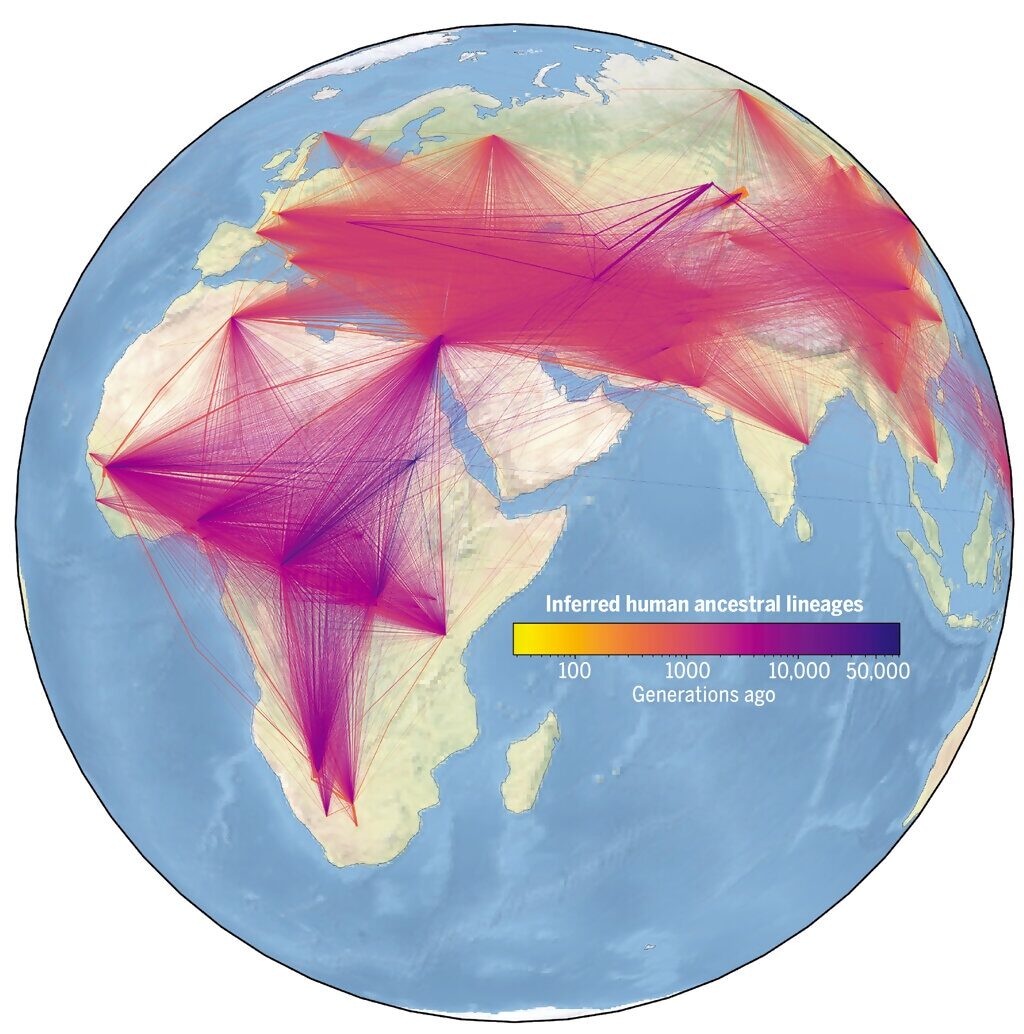

Each line represents an ancestor-descendant relationship in our inferred genealogy of modern and ancient genomes. The width of a line corresponds to how many times the relationship is observed, and lines are colored on the basis of the estimated age of the ancestor.

Researchers using modern and ancient genomes have created the largest human family tree ever made, reports Jack Guy of CNN.

An international team of scientists combined genetic reports of 3,609 individual genome sequences from 215 populations around the globe to produce a massive family tree that identifies nearly 27 million ancestors and where they lived, per U.S. News and World Report.

"We have a single genealogy that traces the ancestry of all of humanity and shows how we're all related to each other today," Anthony Wilder Wohns, leader of a new study published in the journal Science, tells CNN.

Wohns, a postdoctoral researcher at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass., states the study uses ancient genomes from samples dating from more than 100,000 years ago.

"We can then estimate when and where these ancestors lived," he says in a statement. "The power of our approach is that it makes very few assumptions about the underlying data and can also include both modern and ancient DNA samples."

Scientists at the Big Data Institute of University of Oxford developed the algorithms needed to process the huge amount of data involved with this research, reports CNN.

"This study is laying the groundwork for the next generation of DNA sequencing," says Yan Wong, one of the study's principal authors and an evolutionary geneticist at the institute, in the statement. "As the quality of genome sequences from modern and ancient DNA samples improves, the trees will become even more accurate and we will eventually be able to generate a single, unified map that explains the descent of all the human genetic variation we see today."

Per Will Dunham of Reuters, the research study helps show the scope of human genetic diversity and establishes how people around the world are related to each other. Researchers have confirmed that the human species started in Africa before migrating to other parts of the globe.

"The very earliest ancestors we identify trace back in time to a geographic location that is in modern Sudan," Wohn tells Reuters. "These ancestors lived up to and over 1 million years ago — which is much older than current estimates for the age of Homo sapiens — 250,000 to 300,000 years ago. So bits of our genome have been inherited from individuals who we wouldn't recognize as modern humans."

Over the years, researchers have amassed a mountain of information about the human genome. The researchers say their new study helps make sense of that data from a larger perspective, reports George Dvorsky of Gizmodo.

While more research is needed to understand the full results of the study, scientists are already finding interesting — if not controversial — clues in the family tree. Evidence suggests that humans may have populated the Americas much earlier than originally suspected. According to archaeologists, humans first arrived in North America about 20,000 years ago.

"Our method estimated that there were ancestors in the Americas by 56,000 years ago," Wohn tells Times Live. "We also estimated significant numbers of human ancestors in Oceania — specifically Papua New Guinea — by 140,000 years ago. But this is not firm evidence like a radiocarbon-dated tool or fossil."

The researchers are hopeful this new genealogical mapping technique will be useful to other scientists in the future. They believe it could result in breakthroughs in medical research on humans and other species because of the way it stores massive amounts of data.

"While humans are the focus of this study, the method is valid for most living things; from orangutans to bacteria," Wohn says in the statement. "It could be particularly beneficial in medical genetics, in separating out true associations between genetic regions and diseases from spurious connections arising from our shared ancestral history."

David Kindy is a daily correspondent for Smithsonian. He is also a journalist, freelance writer and book reviewer who lives in Plymouth, Massachusetts. He writes about history, culture and other topics for Air & Space, Military History, World War II, Vietnam, Aviation History, Providence Journal and other publications and websites.

Reader Comments