The new research was carried out by an international team of astronomers, led by Margot Brouwer (RUG and UvA). Further important roles were played by Kyle Oman (RUG and Durham University) and Edwin Valentijn (RUG). In 2016, Brouwer also performed a first test of Verlinde's ideas; this time, Verlinde himself also joined the research team.

Matter or gravity?

So far, dark matter has never been observed directly — hence the name. What astronomers observe in the night sky are the consequences of matter that is potentially present: bending of starlight, stars that move faster than expected, and even effects on the motion of entire galaxies. Without a doubt all of these effects are caused by gravity, but the question is: are we truly observing additional gravity, caused by invisible matter, or are the laws of gravity themselves the thing that we haven't fully understood yet?

To answer this question, the new research uses a similar method to the one used in the original test in 2016. Brouwer and her colleagues make use of an ongoing series of photographic measurements that started ten years ago: the KiloDegree Survey (KiDS), performed using ESO's VLT Survey Telescope in Chili. In these observations one measures how starlight from far away galaxies is bent by gravity on its way to our telescopes. Whereas in 2016 the measurements of such 'lens effects' only covered an area of about 180 square degrees on the night sky, in the mean time this has been extended to about 1000 square degrees — allowing the researchers to measure the distribution of gravity in around a million different galaxies.

Comparative testing

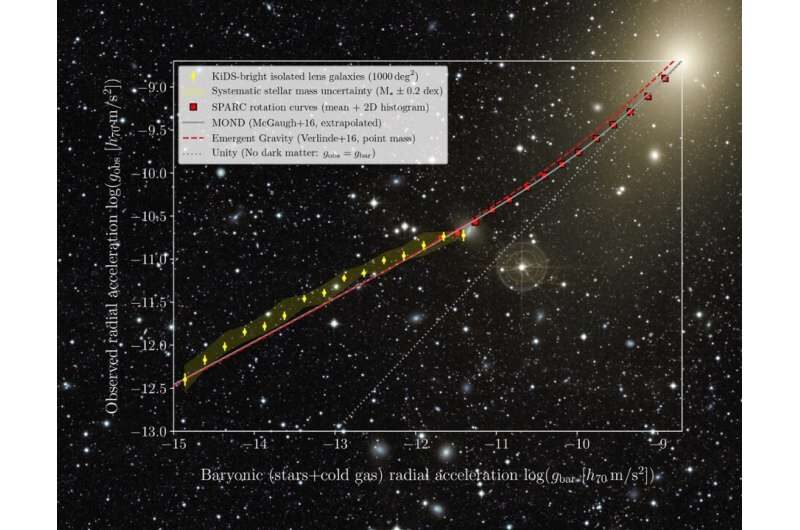

Brouwer and her colleagues selected over 259,000 isolated galaxies, for which they were able to measure the so-called 'Radial Acceleration Relation' (RAR). This RAR compares the amount of gravity expected based on the visible matter in the galaxy, to the amount of gravity that is actually present — in other words: the result shows how much 'extra' gravity there is, in addition to that due to normal matter. Until now, the amount of extra gravity had only been determined in the outer regions of galaxies by observing the motions of stars, and in a region about five times larger by measuring the rotational velocity of cold gas. Using the lensing effects of gravity, the researchers were now able to determine the RAR at gravitational strengths which were one hundred times smaller, allowing them to penetrate much deeper into the regions far outside the individual galaxies.

This made it possible to measure the extra gravity extremely precisely — but is this gravity the result of invisible dark matter, or do we need to improve our understanding of gravity itself? Author Kyle Oman indicates that the assumption of 'real stuff' at least partially appears to work: "In our research, we compare the measurements to four different theoretical models: two that assume the existence of dark matter and form the base of computer simulations of our universe, and two that modify the laws of gravity — Erik Verlinde's model of emergent gravity and the so-called 'Modified Newtonian Dynamics' or MOND. One of the two dark matter simulations, MICE, makes predictions that match our measurements very nicely. It came as a surprise to us that the other simulation, BAHAMAS, led to very different predictions. That the predictions of the two models differed at all was already surprising, since the models are so similar. But moreover, we would have expected that if a difference would show up, BAHAMAS was going to perform best. BAHAMAS is a much more detailed model than MICE, approaching our current understanding of how galaxies form in a universe with dark matter much closer. Still, MICE performs better if we compare its predictions to our measurements. In the future, based on our findings, we want to further investigate what causes the differences between the simulations."

Thus it seems that, at least one dark matter model does appear to work. However, the alternative models of gravity also predict the measured RAR. A standoff, it seems — so how do we find out which model is correct? Margot Brouwer, who led the research team, continues: "Based on our tests, our original conclusion was that the two alternative gravity models and MICE matched the observations reasonably well. However, the most exciting part was yet to come: because we had access to over 259,000 galaxies, we could divide them into several types — relatively young, blue spiral galaxies versus relatively old, red elliptical galaxies." Those two types of galaxies come about in very different ways: red elliptical galaxies form when different galaxies interact, for example when two blue spiral galaxies pass by each other closely, or even collide. As a result, the expectation within the particle theory of dark matter is that the ratio between regular and dark matter in the different types of galaxies can vary. Models such as Verlinde's theory and MOND on the other hand do not make use of dark matter particles, and therefore predict a fixed ratio between the expected and measured gravity in the two types of galaxies — that is, independent of their type. Brouwer: "We discovered that the RARs for the two types of galaxies differed significantly. That would be a strong hint towards the existence of dark matter as a particle."

However, there is a caveat: gas. Many galaxies are probably surrounded by a diffuse cloud of hot gas, which is very difficult to observe. If it were the case that there is hardly any gas around young blue spiral galaxies, but that old red elliptical galaxies live in a large cloud of gas — of roughly the same mass as the stars themselves — then that could explain the difference in the RAR between the two types. To reach a final judgement on the measured difference, one would therefore also need to measure the amounts of diffuse gas — and this is exactly what is not possible using the KiDS telescopes. Other measurements have been done for a small group of around one hundred galaxies, and these measurements indeed found more gas around elliptical galaxies, but it is still unclear how representative those measurements are for the 259,000 galaxies that were studied in the current research.

Dark matter for the win?

If it turns out that extra gas cannot explain the difference between the two types of galaxies, then the results of the measurements are easier to understand in terms of dark matter particles than in terms of alternative models of gravity. But even then, the matter is not settled yet. While the measured differences are hard to explain using MOND, Erik Verlinde still sees a way out for his own model. Verlinde: "My current model only applies to static, isolated, spherical galaxies, so it cannot be expected to distinguish the different types of galaxies. I view these results as a challenge and inspiration to develop an asymmetric, dynamical version of my theory, in which galaxies with a different shape and history can have a different amount of 'apparent dark matter'."

Therefore, even after the new measurements, the dispute between dark matter and alternative gravity theories is not settled yet. Still, the new results are a major step forward: if the measured difference in gravity between the two types of galaxies is correct, then the ultimate model, whichever one that is, will have to be precise enough to explain this difference. This means in particular that many existing models can be discarded, which considerably thins out the landscape of possible explanations. On top of that, the new research shows that systematic measurements of the hot gas around galaxies are necessary. Edwin Valentijn formulates is as follows: "As observational astronomers, we have reached the point where we are able to measure the extra gravity around galaxies more precisely than we can measure the amount of visible matter. The counterintuitive conclusion is that we must first measure the presence of ordinary matter in the form of hot gas around galaxies, before future telescopes such as Euclid can finally solve the mystery of dark matter."

Comment: And they've yet to factor in plasma's role in space: Why the sun's atmosphere is hundreds of times hotter than its surface

See also:

- The Sun is stranger than astrophysicists imagined

- Cosmic voids revealed in most detailed map of the universe defy our understanding of physics

- Mysterious 'wave' of star-forming gas may be the largest structure in the galaxy

And check out SOTT radio's: