This week on MindMatters we interview Dr. Simon about his work and the frameworks that have helped thousands to understand their relationships, as well as provided assistance for those wishing to look into the mirror of their own weaknesses, narcissism and failures of character - reminding us that while it's valuable to see the egregious behavior of others, it is also crucial to be able to recognize and correct our own failings.

Dr. Simon's website: drgeorgesimon.com

Running Time: 01:29:00

Download: MP3 — 81.5 MB

Here is the transcript:

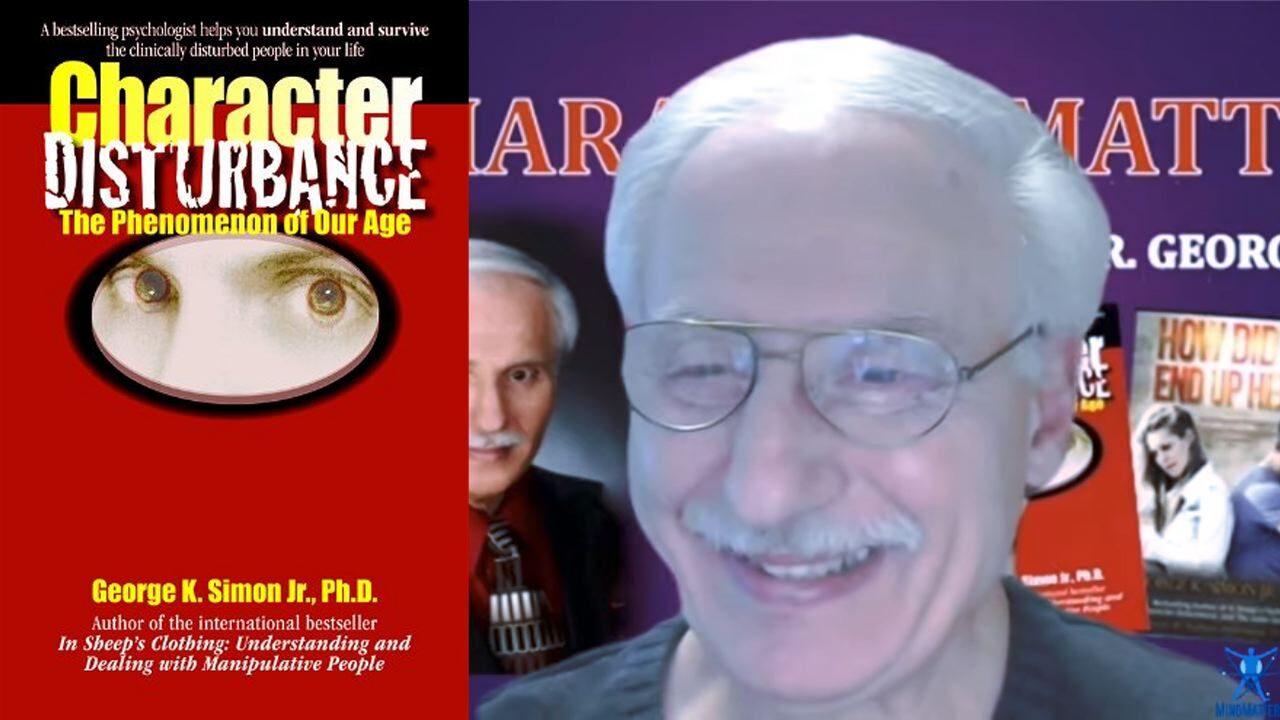

Harrison: Welcome back to Mind Matters everyone. It is a new year, our first show of the year and today we are pleased to be joined by Dr. George Simon, Jr. George is the author of several books. We've got some of them here. The first one we read here is In Sheep's Clothing-Understanding and Dealing With Manipulative People and then following that one, this one. I was very happy when it came out. It was a book I wanted to read and then loved reading: Character Disturbance-The Phenomenon of Our Age. And then a third one, The Judas Syndrome-Why Good People Do Awful Things.

I guess I should say this one came out in 2013. Your first book George came out originally in 1995, 1996? Is that correct?

George: 1996, believe it or not.

Harrison: 1996. And then you've written two books since then. We'll talk a bit about them but first, before we get into that, I just want to welcome you to the show George. It's a pleasure to meet you and we're looking forward to talking to you.

George: Thank you Harrison. Happy to be here.

Harrison: Great. To start out with, could you tell us about the two books that we haven't read, that we don't have here. What's the last book you have published and the one that you're working on right now.

George: The last one published was How Did We End Up Here? My co-author, Dr. Kathy Armistead was my editor for The Judas Syndrome and she said if you do not write a book about how people get into these crazy relationships and what they can do to make sure that that doesn't happen again and how they can rebuild their lives then I'm going to write it for you. {laughter} And so we had a cooperative venture to write that book and then she also partnered with me in the writing of my current book which has been re-titled. The initial title was The 10 Commandments of Character. It's an expansion on the principles that I outlined beginning on page 140 of my book Character Disturbance. Ever since that book came out I've gotten thousands of emails from people all over the world asking me to expound on those things more.

So we did fashion a book called The 10 Commandments of Character that did expound on that but it didn't take into consideration, I thought adequately enough, all aspects of personal growth including spiritual growth. So I have been rewriting it for the last two years and I'm really on fire lately, especially because of recent events because I think it's so urgent, that I think we're getting there. Now it hopefully won't be long before the newly titled Essentials For the Journey-Embracing and Living the 10 Commandments of Character comes out in print. I'll be happy to let you know when that happens.

Harrison: Great! Looking forward to it. You said something about How Did We End Up Here? that leads me to one of the questions I wanted to ask you. I am assuming that that book is primarily about difficult relationships and what a couple might say after years of conflict - how did we end up here? Maybe divorce or some extreme relationship conflict that leads to a situation where it just seems like there's nowhere to go.

George: Mostly it's 'How did somebody I thought was the be-all and end-all and hung the moon, how did somebody like that turn out to be such a schmuck?!' {laughing}

Harrison: Okay. I was curious if you could tell us a bit about your practice and how your actual clinical work led to you learning about and becoming an expert on these types of relationships and these types of character disturbed individuals, people with extreme personality disorders, basically a bit about that background and how that helped you navigate this strange world that a lot of people aren't aware of.

George: Well you asked a really great question. I say in the opening lines of my new book that will be coming out, that I've had the most unusual career, actually the career of a lifetime because I've gotten to do two things that normally don't go together. I've had the privilege of helping individuals who have survived toxic relationships, rebuild their lives and grow and help ensure that they don't fall into similar traps again and become more empowered. So that's been really edifying work.

But I've also had the chance to work with people who really needed to be better people and at some point in their life they actually came to that conclusion. But that kind of work - and this is the important part because there's a lot of people who think that you can't unbake a cake and that there's just no hope for people with character disturbance - the biggest problem when somebody finally gets a clue that they really need to do some changing, the biggest problem is that traditional methods of helping them don't work. They're not meant to work. So very few folks have the tools to help folks who actually want to be better people.

So I had to do a whole heck of a lot of clinical research and then I was blessed with some incredible opportunities, including consulting to juvenile detention centers and programs and prisons, all kinds of places. I developed worksheets and I would hand them out to people who were of the most egregiously disturbed character and they would read these worksheets and they'd say, "Oh my goodness! This is me! This is what I do! How do I change this? Is there another way? I think there must be but I haven't a clue." And all of a sudden I realized that there was actually a way to work with and reach some of these folks too.

Now true, there are some folks who are so seriously disturbed that they exceed our present abilities to help. But the biggest problem has to do with the fact that most folks aren't trained in the methods that work. So I've had a very uncommon career helping two different groups of people in two very, very different ways.

Harrison: I get the impression from the books that I have read that a lot of the cases that you must have experienced have been with types that didn't realize there was a need for any change, that didn't want to change and basically had zero kind of self-insight. So how would you fit that into that aspect of your career? What was it like dealing with a couple, with someone one-on-one like this, or how did it affect in general with dealing with that many people who didn't want to change or didn't accept that there was anything to change about themselves?

George: Boy, once again your question is so good. As a matter of fact, nobody's really asked about it that way before. I'm afraid it would take us about three programs to answer that properly. {laughter} But let me see if I can condense it a little bit.

We're taught as helping professionals early on that the basis of any helping relationship is unequivocal trust. What I found, what would just kind of happen, I had an epiphany of my own, is that I've been taught all of these things about why people do things and I found that when it came to character impaired people, none of those things that I was taught, none of those axioms helped. I was taught for example, for one thing, that they really don't know what they're doing, that they're motivated by unconscious fears and insecurities so they don't really know what they're doing and your job is to help them see.

Well in my workshops I tell the clinicians we think they don't see. That's not the problem. They see this bind. The problem is they see but disagree! There isn't a thing you can't tell them that they haven't heard a thousand times before. They've gotten all kinds of feedback from maybe hundreds of sources. But they've developed a way of doing things and it seems to work! So why should they change it?

So once you get a different head about you, as a helping professional, and once you DARE to lovingly confront unhealthy interpersonal behaviour, which has to show itself in the interaction between the impaired character and the counsellor, it has to show itself, once you confront that lovingly and directly in the present moment and invite change, the whole ballgame changes. Everything changes. It's the beginning of doing not as you're used to doing, but doing a little differently and learning in the process.

There's an old axiom that I have come to appreciate the wisdom of because you know I mention in my books that I operate within the cognitive behavioural paradigm. In a lay person's parlance, that means that what we think and how we think and our attitudes influence what we do. So if I'm a man in a relationship and I think that woman is inherently inferior and is meant to be dominated then I'm going to treat her in a particular way.

So what clinicians usually do is work on the cognitive side of things, getting people to change their mind in the hope that it will change their behaviour. Well it doesn't work that way! What works is changing your behaviour because it will change your mind.

So I followed this axiom, that it's a lot more efficacious - that means it's a lot more effective - and it's actually a lot simpler, to act your way into a new way of thinking than it is to think your way into a new way of acting. So I long ago stopped reasoning with people {laughter} and just invited them to do differently and then when they did, started reinforcing them very heavily for so doing. And after a while it gets catching.

Elan: Well that's so interesting because your approach George is counter-intuitive and as you say, it works. I can remember reading Character Disturbance and you present this spectrum of behaviours from healthy to maladjusted and to character disturbed. What was interesting for me is in recognizing certain things I have done in my life and behaviours and actually getting a little shocked because of seeing certain things described by you as on the spectrum of character disturbed. So I would say that I like to think of myself as a relatively aspiring healthy individual...

Harrison: They all do. {laughter}

Elan: Yes, especially me. But it is really a very practical, I think, approach to looking at behaviour, action and thought processes for the person who is relatively well adjusted. So these books aren't only helping one to recognize this framework of character disturbance and narcissism in others but it's a kind of simultaneous work on the self by seeing how it exists in one's self. I did just want to say this as well. On YouTube right now, if anyone has noticed, there is a plethora of YouTubers speaking out on this very subject George and I would daresay that this movement to understanding narcissism and character disturbed people is in no small part due to your work. In Sheep's Clothing has been around for 25 years, as we said at the top of the show. This is a hugely influential book.

So I just wanted to tip my hat a little bit more to you here because the frameworks that you've created for people to recognize interpersonally and within themselves, those traits that could and should be worked on, has provided a whole movement I think.

George: Let me respond to that because I sincerely appreciate your kind word but I have to tell you, something compelled me to write that book. When I was in school I tried my hand at writing and my professors told me that basically it was not my calling. {laughter} So I never even dreamt that I would do it. But I was compelled and for two reasons. One is I had uncovered something in my work with aggrieved relationship partners in toxic relationships, especially with manipulative partners, I'd uncovered something that we now call the gaslighting effect. We didn't have a name for it then. But it's that crazy-making feeling when you just know that there's something not quite right about what just happened but the person who's doing whatever they're doing has got you thinking that you're just crazy for thinking it.

I kept seeing this over and over and over again and I thought, "This is a phenomenon. It's a real phenomenon. And if all the people that I'm dealing with are experiencing it, there must be hundreds of others out there who are experiencing the same thing." So even after 20 some years, I still get hundreds of emails from all over the world from people who will say that just those opening words in the book where I say you're not crazy, maybe you need to trust your gut, there are people who are just like you think, just those words changed everything.

So I was compelled to do that by something. I'm not going to try to define that something. You can call it whatever you want to call it, but there's something bigger than all of us and it kicked me in the butt and said, "You do this." It was a labour of love but because I'd not done it before and because I didn't trust myself to do it because I'd been told that I couldn't, I just had to do it anyway. The rest is history.

Harrison: It was originally an independent publication. Was it self-published?

George: Yeah. I created a small company. I had gone to New York and I'd dealt with a big company and we thought that the original manuscript was going to get really big pre-emptive offers. I was young, naïve. I didn't know what was happening. They were talking these hundreds of thousands of dollars in advances and all this kind of stuff. I was in way over my head. But as it turned out, it was a time in the market that was horribly slow and basically the feedback I got was the book had a lot of substance but it's not what would sell at the time so it was going to have to be re-written into some kind of snazzy, jazzy - I don't even know how to describe it - but it was not going to be the book of substance that I wanted to write.

My wife and I thought about it for the longest time and I finally said no and I wrote the book that I wanted to write and independently published it. Well it didn't take long for me to find out that I'd done the right thing. So when the time came for me to go with a royalty publisher, I was able to cut a really good deal and to get the benefits of a house behind me and then I wrote an updated edition in 2010. But only Road Less Traveled by Scott Peck has even come close to the durability of In Sheep's Clothing. It still sells more every year than it did the year before.

Harrison: Wow!

Elan: Wow!

George: After 20-some years.

Harrison: That's amazing. So Elan talked about how widespread a lot of these discussions are now and I was listening to part of an interview you did last year where the two of you were talking about the responses to the things that you say in lectures or things of that sort and how starting out you'd get a lot of blank stares back in the 1990s or maybe even before that, but that nowadays when you lay out some of these concepts the eyes will go wide and people will start nodding like they recognize it and have seen it.

George: Right.

Harrison: It would be hard to gauge necessarily how much that is your book influencing the zeitgeist and the mind of the masses. What do you think that is? How come you think that people are more receptive nowadays? Do you think it's because of your book?

George: Well you know it's so interesting and that's why I think it's so important that whatever that something is out there, whatever that bigger something is out there, that we pay attention to it and listen to it because when I was first giving these workshops, it wasn't just that people were looking at you blankly. I did grand rounds at one of the medical institutions just here in town where people walked out! I was trying to say that character mattered at a time when the medical profession was thinking of throwing the part of our official book, the DSM, they were thinking of throwing the whole personality section OUT because the thinking of the time was that it doesn't really exist, that we're all just our biochemistry and that if we could just find the right brain rebalancing chemical we could fix everything! That was the zeitgeist of the time!

So it wasn't just that folks were looking at me blankly. They thought "This guy is just ancient. He hasn't got a clue." So things have really changed. I don't know how you could process the events of yesterday [rioting/invading US senate], which literally had me crying, which broke my heart. I don't know how you could discount the paramounts of importance of character. Even some folks who I have huge disagreements with and who I think are very misguided in their ways to solve some of our social problems, eventually had to stand up and say, "You know what? There are certain values here that are being absolutely trampled upon and we can't stand for it anymore." Well that's what character's all about.

The only thing that doesn't really surprise me, maybe I could explain more about that later, but that we had to sink to such depths to appreciate the fact of how much character matters. That's very sad to me. But I do understand it.

Harrison: One of the thoughts I have on that is that there seems to be this rise in awareness or at least a rise of interest and I think part of that is a recognition of what's going on because when something becomes so prevalent it becomes more obvious. So I think a lot of people looking around the world at pretty much every aspect of life and every aspect of politics will see something there. So on the one hand that seems like a good thing, that there's a bit more awareness of what's going on but I'd say the negative is that the reason for that awareness is the prevalence of the character disturbance in the first place which must be at epidemic levels in order to give rise to that awareness.

George: Oh my goodness! Now you haven't had time just yet probably, to read the blog post that I posted today.

Harrison: No I haven't.

George: Okay. Well that's exactly what I was talking about.

Harrison: Oh wow! {laughter}

George: Yeah, that's exactly what I was talking about on the post today.

Harrison: Okay, well I'll make sure to check it out after we do the interview. {laughter}

George: You know, we've become desensitized because the most insidious thing about this character pandemic is that most of the forms of narcissism out there are not as venal and not as egregious and not as horrifying. So we give it a pass. We're so used to it we barely notice it anymore. There's so much egocentricity out there. There's so much lack of awareness and concern of our inherent interconnectedness, the fact that everything we do impacts something or someone else and that we're all in this together. There's such a lack of awareness of that. It's so deeply built within the fabric of our culture that until something gets really seriously awry, we don't even pay attention to it.

Earlier on I was scratching my head. I thought, how bad does it have to get? What does a person have to say or what does a person have to do for what used to repulse us, to begin to repulse us? And the answers that I came up with were not pretty, not pretty. One of the answers - I know we don't want to get political - but one of the answers that I came up with is that when people don't feel heard, when people don't feel acknowledged, regardless of where they might be or how we might look at them in their own personal development, they will support anyone or anything that they think gives them greater presence and recognition and they will dismiss other things that are important because of that, because it's so important to them, including the importance of character. By the way, including the importance of their own character in the process.

I think that's where we are, sadly. I belong to several different organization all trying to bridge the gap and make peace and I can tell you that in every one of those organizations there's still for me a very big missing piece because a lot of folks come to the table with the idea that their side has an answer and that the purpose of the meeting is to get the other side to appreciate the wisdom of their answer. As opposed to both sides standing in awe of something much bigger and then humbly working toward the loftier goal. We've lost that sense and that's the spiritual component of character that was missing from the first draft of my more recent soon-to-be-published book and that's why it has meant so much to me to get it right. It's not going to be out there until it's right and it's getting closer now but it's not quite right just yet.

Harrison: Good.

Elan: George, so that article on your website that you just put out is called Narcissism Desensitization Impairs Recognition. I had a chance to read it earlier and I thought yeah, if you can't recognize, if you're desensitized to the signs, to the framework, to the identification of character disturbed behaviour, then you're swimming in it. It becomes ubiquitous. It's something that is undifferentiated from anything else.

So you've been writing about this for quite a while and you've noticed that we've come to a kind of tipping point it would seem. So on the show we've talked about social contagion, ideologically possessed individuals. We've tried to come at this problem from as many different angles as we could. These problems have always been with us.

George: Yes.

Elan: From the dawn of time.

George: Sure.

Elan: But what do you think has been exacerbating, if anything? What is it about western culture in particular that has made it so rife for the pestilence, the boil to come to the surface this way and become so putrid and toxic?

George: Okay. From a practical standpoint, from a practical standpoint, demographics. We were a very, very different country. When you look at the electoral map you can always see these differences glaringly in the polarization. We were a different country when we were a much more rural frontier country. Now I'm not touting that as good necessarily. I'm just saying we were very different. There were negatives. I mean we've had plenty of times in our past that rightfully should make us all quite ashamed.

So I'm not saying, "Boy all we need is the grand old good old days." That's not what I'm saying. But one of the things that we lost in the process, despite this age of so-called connectivity, is that we lost our sense of community. And how that happened is because our first experience with community is with family and when families become too dysfunctional the inmates take over. This is just natural, normal and it's actually healthy. When you can't trust the people who are supposed to take care of you, you have to learn to take care of yourself. The problem is, as a skull full of mush you don't know how to do that! We used to have people guiding us that we could trust. When your father is not there and your mother is strung out on drugs and can't even attend to you, you haven't got a prayer.

It's nobody's fault but it's everybody's dilemma and we can no longer just let it be everybody's individual situation to figure out for themselves. We are all in this together. We are inherently a family. We are a dysfunctional family for sure but we're inherently a family but we don't have the family experience and grounding to tell us how to tend to and live with our individual differences and how to help guide those folks along who are struggling, starting with making sure that we're in a position ourselves within our own character development to actually facilitate that process.

So I think the good news in all of this is, it's the same thing that happens on an individual level when somebody finally decides to change. Sometimes that great something out there is merciful enough to us to let everything come crashing down around us and then we have one of two choices. Change or perish. That happens in an individual's life too many times and so it saddens me that we had to come to this point, but what I hope will be the diamonds in the pothole - that's an old axiom too, that mistakes are like diamonds in a pothole. The pothole can wreak some diamonds but there are diamonds many times in the potholes, the little gems that will help us do better. My hope is that I can contribute to us learning the lessons that we need to learn from this experience.

But more specifically, what happened over time to get us to this point culturally is that it's a vicious cycle. As more and more character impaired people entered the society and challenged character fostering institutions and traditions and seem to prosper despite their poor character and rose to positions of power and influence, as all of that happened, then the norms, the standards, the institutions that helped foster character growth in all of us, those things eroded. And the more they eroded, the more character dysfunctional people were created. It's a classic vicious cycle with character impaired people populating the culture and then the culture erosion causing even more character dysfunction. Classic vicious cycle and it had to break and we're at the breaking point now.

Harrison: Well a few minutes ago George, you asked a hypothetical or even rhetorical question about where do things have to go before people see that billboard in their face, that there's something they need to learn about and realize about what's going on. Like you said, in a relationship that can be the rock bottom point where things just totally fall apart. You said that you've thought about a lot of the possibilities and some of them are quite dark. Maybe it's just my dark mind, but I tend to look at the dark ones too.

So I look at my study of history, limited as it is, and look at other countries and what has happened there. I try to think of what are some of the worst case scenarios. Well if I look at the Russian Revolution or a lot of what happened in Eastern Europe in the 20th century or Mao in China where the way I see what happened there is - perhaps I don't know enough about the history before then - perhaps there were periods of time where something similar was going on in the sense of a corruption of character and previously held values and where things fall apart.

But then once things fall apart, once there's a revolutionary scenario, whether it's provoked by a world war or some kind of natural disaster where things just cross that tipping point to the point where there's too much to bear, then things actually get exponentially worse than they were in the lead-up to it, where beforehand you might have had all of this corruption in the system and you might have had the prevalence of vast inequalities, character disturbance and narcissism, etc., etc. Then once everything breaks down, then there's a branching that can happen. I think you said something similar, right? "We can actually build something out of it."

But the other option that happens is that all of that evil you could call it, concentrates and then you get what psychologist Andrew Lobaczewski called a macrosocial psychopathological phenomenon where you get this network, this rearranged social hierarchy where, compared to what it was previously, it is living hell.

So that's where my mind goes in terms of what's the worst case scenario. What might it take for people to see all this? As bad as things are at present, it might take something exponentially worse to the point where society is completely unrecognizable and it's staring you in the face and at that point there's not a lot you can do.

George: Ah! But here's the other side of that.

Harrison: Okay.

George: When we use this mind to ponder these big issues and what the heck we could possibly do to change things, it truly is mind boggling. It gives me a headache. There are no easy solutions and besides which, we don't have that kind of power. The power we do have however, is how each one of us meets the moment and that's why character matters and that's why I'll probably die speaking about it because like how do you eat an elephant? One morsel at a time. How do you change the world? Dr. Martin Luther King knew the answer to that. One heart at a time, starting with mine. That's where we have power. We have power not to alter the future, not to change the past, but we have the power in any encounter, to meet that moment with a right heart.

And this is what my epiphany was in therapy because you know we're all actually good potential therapists for each other. The magic in therapy is how the moment ends up transforming. That's the magic of therapy and if that moment doesn't transform, the whole process has been pretty worthless. I have so many people who have reported to me experiencing what I now call in my workshops therapy-induced trauma. They dragged their character impaired relationship partner in finally, they browbeat them enough and then they reluctantly say, "Alright, just to get you off my friggin' back, I'll go." And then they end up in the therapist's office and they try this technique and that technique.

Maybe even the character impaired person is so skilled in the art of positive impression management that they get the therapist thinking that the other person's the crazy one. Nothing good comes of the whole process and so the person leaves even more dejected than they were. If the encounter doesn't transform then something's wrong with the encounter. I firmly believe the wisdom of the sages when they say that only love, real love, not all of the hundreds of things that we call love, transforms and it has to start with us! If I'm in an encounter with another human being, say even in my office with someone who has narcissistic inclinations, if I'm loving myself appropriately, some things are going to be off the table and if that person is going to have a prayer of learning to love better, some other things are going to have to be off the table.

Now how, how I encourage a more loving, healthy response to occur in that moment that I have with you, right here right now in my office, is everything and is potentially transforming. And it's something that each one of us can do every single time we encounter another human being on this planet. We have it within us to change the world but it has to start with us! It's really as simple as that. Simple does not equate to easy. If loving were easy everybody would do it. It's not easy. And it masquerades as many other things.

Elan: I'd like to ask you something George because throughout the show you've repeated a couple of times that something compelled you to write In Sheep's Clothing and you've alluded to how some of the books didn't have the spiritual component that you wanted them to have. Then you had written the book The Judas Syndrome which was intended to be read mostly by Christians who might have some understanding or some connection to faith in the higher but could perhaps learn to strengthen it.

This would seem to be a very important dimension to growth towards becoming more individuated, healthier and to, in potential, help others. So I was hoping you could talk a little bit about your faith and where you think faith comes in with self-growth and development and healing and that sort of group of issues.

George: Well it's certainly more than religion for me. Way bigger than that. Most conflicts in the world have been inspired by or promulgated by religious differences. So the narcissism that I see in all organizational systems of belief is that if we could just get everybody to think like we do then we could have peace, right? How's that working for you? {laughter} How's that work for the human race? That's why I'm even hesitant to apply a word to it, whatever that something was that compelled me.

You know, within the Jewish tradition and even within the Christian tradition, if you read Moses's inquiry to this something that he encountered in the burning bush and when he asked for an identity god supposedly said back to him basically, 'None of your business'. 'I am that which I am. You can't possibly wrap your little head around it. Well yeah, so go back and tell the Pharaoh that I Am sent you' for lack of anything better. Well, how's that for a name or an identity?

We can be so arrogant. It's just part of our inherent make up and that's the paradox of life for me. The paradox of life is if we're actually meant for something better, why do we have to start out so primitively? Why are we wired the crazy way that we are if we're destined for something more? It's a paradox, isn't it? And I think all of the great systems of belief in the world have come to their own vain answers about why and how and how to get there. And you can find kernels of beautiful truth in every one of them. But I frankly think that the energy that I know is real is way bigger than any of those self-righteous conceptualizations.

So even though I might use some of the practices myself and even though I find beauty in all of the interfaith dialogue that I have with folks of other persuasions, I don't put my faith in any rite, ritual or practice. There's something bigger that I believe in that is bigger than all of that too. That's just where I am. I hope that answers your question {laughter} because it's pretty vague. It's vague to me.

Elan: Well when you were saying that I was thinking, "Okay, so it's kind of an agnostic inspiration that you..."

George: No! It's not agnostic. I have to challenge that. I don't just believe that there's a bigger something. I know there is. I know it because that bigger something just took a big fat two-by-four and whooped me upside the head and let me know that it's real. But I think it's vain to even attempt to define it. If you get it, and if you really understand the relationship then you act like it. And that's how you know people who are enlightened versus those who aren't. They behave differently.

You can look at them all through history and they're not necessarily perfect people. We don't have to be without flaws. We just have to be connected to something bigger and pay attention and when it kicks us or pushes us to do something, it behooves us to listen. I'll give you another example.

I think I mentioned on the blog that I'd never actually composed a song before. I'm musical. The only instrument I've ever played has been my voice but years ago because of some surgeries and whatnot and some other neurological problems, I lost that. So I've never been much of a musician but I've always loved music. In 1997 a melody started playing in my head. I had no idea where it came from. It just started playing over and over and over and I thought what the heck is this all about and what's it for? Part of me thought I might be going a little nuts.

Eventually collaborating with my wife and my brother I found some words for it. I only knew one phrase that was meant to be in there and that was America, my home. This is the truth. I had no idea why we would record this song, why we would get some musicians together and a vocalist and put this thing together because it was going to go nowhere, absolutely nowhere except on a cassette tape that I would listen to in my truck at the time. But I just had to do it. But the day after 911 the universe would show me what it's purpose was and it wasn't even a 911 song.

So you just never know what's going to happen or why but you have to pay attention. I sincerely believe that everybody, when they stop using this {points to head} and they uncover their deeper more authentic mind, has that voice talking to them in there. The problem is we think too much with this and don't listen too much to what's going on in here {heart area} where the source resides.

Harrison: Incidentally that reminds me of an interview I was just listening to with Wim Hof. Have you heard of Wim Hof? The Ice Man?

George: No.

Harrison: What country is he from? Do you remember? Dutch? He's not American but he's famous. For years he did cold adaptation. He'd swim in ice cold water every day and he's become quite popular, quite well known for this because that has led him to some remarkable abilities. He can hold his breath for a long time under freezing cold water, swim. He swims under the ice in the arctic and he has a remarkable control over his own body and his own physiological processes. At one point six years ago he had participated in an experiment and got e-coli injected into him and showed no immune response.

So he's gotten a great deal of control over his body and it has resulted in some amazing things. So I was listening to an interview with him that was just done in November with Jordan Peterson who asked him, "Well how did this start? How did you first get the inspiration for going into the cold?" He said, "Oh, it was just a gut feeling." That was it. He just knew that he had to go in the cold. He made the same point you do, that we're so cut off from that voice that speaks to us. It isn't what you think. It's not a thought process as we normally think of a thought process. There is some kind of - I don't even know what to call it - communication, something that can communicate with our mind, that's greater than our mind and more insightful than our mind is. Maybe the source for the inspiration, like the inspiration for that melody or it might be the inspiration for a choice that has to be made, a decision that has to be made that you don't know and that might present itself as 'this path, not that path' and you might not even know why but it shows up and it's so strong.

George: Right. And I think one of the obstacles to that is that we've had a lot of folks in vanity attempting to define who or what god is when very few of us even understand who we are. That's where I think it has to start. That's where I think it really has to start. I think really that's what has mostly driven my work, that inspiration, wherever it has come from. Back in early workshop days I found myself just uttering the phrase, "If we don't get honest with ourselves about ourselves and with each other about each other, we're going to have a hard time making it."

So the real question is to get to know ourselves, what we're really all about, what makes us tick. Because when we know ourselves then we'll actually know our brothers and sisters a hell of a lot better. Then we have half a chance.

Harrison: Are you still good for time George?

George: I am. I usually have all modes of people trying to get hold of me blocked for these things and somehow people are finding a way to sneak through. {laughter} But that's alright. I've got these automatic little reminders that tell them "I'm busy. Sorry."

Harrison: On what you just said, I want to come back for just a bit to the new book that you're working on because you very handily provided the page number for the inspiration for that book here. So I want to read some of The 10 Commandments of Character just so our viewers and listeners get a chance then maybe you could talk a bit about one of them. Or maybe if any one sticks out of what I say we could focus on it because they're really good.

George: Sure. And by the way, a little disclaimer. I have already re-written them a little bit more eloquently but yes.

Harrison: So here they are in their original form, in their unpolished state.

"1. You are not the center of the universe.George: I might say with regard to that last one, I've also really had to reckon with the fact that sincerity itself is also not enough. You can read several texts and several religions talking about the necessity for purity of heart also. There are some folks who are very sincere, in other words without pretense, who are who they are, without any question, no phoniness and frankly no shame. But that's not necessarily a good thing either. So it's not enough to be just sincere. It's important to be both sincere and clean or pure of heart. Which one would you like to talk about because we could talk about all of them at length.

2. Remember you are not entitled to anything.

3. You are neither an insignificant speck nor are you so precious or essential to the universe that it simply cannot do without you.

4. To know, pursue, speak and display the truth to the best of your ability, have the utmost reverence for the truth.

5. Be the master of your appetites and dislikes.

6. Be the master of your impulses.

7. Perseverance, patience and endurance are not really virtues in themselves.

8. Neither your tendency to anger nor your instinct to aggress is inherently evil although wrath is a deadly sin.

9. Treat others with civility and generosity.

10.To the best of your ability have sincerity of heart and purpose."

Elan: I had a question regarding that. Embracing for the journey, embracing and living the 10 commandments of character, the book that you're working on...

George: Essentials for the Journey, yes.

Elan: Yes. So what feature of what you write there George would you say drove you to expand on these thoughts? You wanted it to have the spiritual component and to have an added eloquence. Let me ask you this way. What are you most proud of or what do you think was the accomplishment? What did you set out to accomplish and what do you think is its core value to people who know your work or who want to grow?

George: Okay so let me answer both of those questions the same way because you were asking me about what happened that changed my perspective where I needed to add this additional dimension. You also asked me what I was proudest of. So the answer to each one of those questions is actually the same. I used to be proudest of the fact that I had discovered something important and had put it out there and received some recognition for it. That's pretty darn vain. These days I'm most proud of having listened and followed and that makes all the difference. That's why I'm re-writing this book because I've always been kind of a decent guy as far as behaving myself, being good. It's not enough. It's not enough.

Until we connect up with something bigger and put ourselves at its service, life is pretty empty. It's full of momentary pleasures and addictions and a hell of a lot of pain but it's not living and because we have so many temporary pleasures and so many ways to get addicted - my god! - and so many ways to pretend like we're really connected, on these things (iPhone), texting back and forth, it's crazy and we barely even know our neighbour usually. That's what has happened to us.

So did I invent that? Hell no! Like I said, sometimes I'm kind of a stubborn guy actually in many respects so whatever that something is out there, many times it has to wake me up with a pretty good shake. So these days I'm most - and proud is not even the word - I'm most okay with myself for having listened and maybe being a conduit or something.

Harrison: Great. I think you're frozen on us George. Can you hear us?

George: We lost the internet there for a minute. I'm not sure what happened.

Harrison: The internet went out right after you'd finished your thought so we didn't lose any of that.

George: Oh okay. Good.

Elan: And it was such a wonderful thought that time stood still for us.

Harrison: You blew up the internet with the depth of the thought that you just shared George. {laughter}

George: One of those synchronicities huh?

Elan: It was heard and felt on our end I think and appreciated very much.

Harrison: All I can say is that I agree with that approach and that look at life completely. That is the thing that matters the most and all kinds of other accomplishments don't really amount to much if you're following your call and doing what you're here to do. That's the thing that gives the most not only satisfaction with life, but the feeling that you're actually doing what you're here to do, fulfilling a purpose, as opposed to getting something for yourself, right?

George: Yes. Let me give you a concrete example of that that I can think of. I have a friend who I know always wanted to play the big stage but for most of his life he's played the small stage, I think in part, in large measure because he hasn't figured out why. When you're willing to put everything on the line, sacrifice everything for what you feel called to put into the world, you don't do it to occupy the stage. You do it because something bigger is calling you to do it and if you're meant to be on the big stage you will be. If the message is meant to be heard by a lot of people, it will be. But the important thing is to really follow the call. Sometimes it takes people a lifetime to figure that out.

The other thing about it is that the things that all of the mystics throughout all of the ages have been trying to tell us about the bigger realities of life are just too damn good to be true. They want to open us up to a richness of life and its purpose and its destiny that is way beyond our ability to comprehend or appreciate and the world sets a very, very different standard for us. It tells us basically that we've got to get what we can get, enjoy what we can enjoy and do it fast because tomorrow we could die. So grab as much as you can and acquire as much power and money as you can. This is what we're taught from very early on. Jeez!

Is it a surprise we're in this mess?

Harrison: My response to the bit about the mystics but also applies to the bit about life and society is that meanwhile we can't even get along with our siblings, literally and figuratively. There's a place you've got to start. We're in such a low place character-wise that we've got to do a lot of work to even approach the level of starting with the contemplation of the mysteries.

George: Again, to get back to that question asked before, what the universe was speaking to me in the rewrite of this book, I could just hear the universe telling me, "George, it's not just about being good. You want to tell anybody about character, first of all start with yourself and realize that there were things about you and your own lack of appreciation for the inherent interconnectedness of us all and the way that you were meeting every moment that were very, very lacking. So it wasn't enough for you to be just a good guy. The manner in which you were meeting each moment with every person really needed a lot more attention." Boy, that spoke to me and as I advise in all my workshops, you've got to act your way into a new way of thinking, not vice versa.

So when I started very deliberately to the best of my ability trying to meet those encounters with everybody I met in a very different way, holy moly! What an epiphany! It was just amazing to see what difference could come out of the encounter.

Harrison: George, did you have something that you wanted to finish on that thought?

George: No. Probably my mind would take off in a million more tangents. {laughter}

Harrison: Because that led me to a tangent that I wanted to ask you about. Something in an earlier part of the interview made me think of it. It was the part you just repeated about the reason that treatments for a lot of people with some kind of character impairment doesn't work is because it's using the wrong methods and you laid out your method. That reminded me of a book that you cite in Character Disturbance I believe, Inside the Criminal Mind by Samenow (I don't know how to pronounce it).

George: Samenow.

Harrison: Samenow, that's right. At the end of that book, I believe in the last chapter, he takes you through one of his success stories which you couldn't call a grand success but it was a success in the sense that here was a criminal mind, a bad dude basically who had done a lot of bad things and who, through this process, through interacting with Samenow or was it Samenow's professor - I can't remember, the guy who taught him that he worked with - took him through this process where he could actually live a functioning life not of crime.

George: I think you're speaking of Samuel Yochelson who he wrote his first book with.

Harrison: Yes, that's correct. So I just wanted to know if you see any similarities with what you do because, like we said earlier, there are some people who seem like they're so far gone or so disturbed, maybe some hard core psychopathy like at the top of the Hare checklist, that maybe there's nothing you can do for some people. I want to know how that works out. Maybe you could give a really short case study of what you see change and how you do it. I know that's a huge topic.

George: It really is. It's another visit. But let me speak to one core issue that's really important that has come out of not just my individual work, but also has begun to be supported by research. Back in the late 1960s and early 1970s and 1980s there were all these pop psychology books about the toxicity of shame and if you read any of those books and you adopted their axioms, it was okay to feel guilty about something, it was okay to feel not good about an act you had done but it was never helpful to feel badly about the person you were.

So even therapists were actually instructed in this. Don't deal with people on their character, talk about their behaviour only and what needs to change in their behaviour but don't cast any aspersions. Don't make any value statements. Don't make any judgments because otherwise you'll invite them to feel badly about themselves and that's never any good.

Well we have witnessed what shamelessness looks like and believe me, it ain't pretty! So what I've come to find in my work with even the most severely disturbed characters who found somehow the resources to be better is that not one of those persons ever changed out of a feeling of guilt. I know some abusers who actually felt awful every single time they lost it and beat the crap out of their partner. But you know what? It didn't change them. It didn't stop them from doing it again.

The only thing that made a difference for any of the people who have actually managed to turn their lives around in some way meaningfully was when they took that look in the mirror and they said to themselves, "You know, I don't like you anymore, the way you think, the attitudes you hold, the way you treat people, the way you even think of yourself, the person you want to be or present to the world. Not pretty." Only healthy shame saved them. We now know what shamelessness looks like. It's not pretty.

Now does that mean that some people who bear toxic, unreasonable shame that was never deserved shouldn't be rid of it? No, it doesn't mean that at all. People who bear unrealistic, horrendous shame for things that were never their fault need to be rid of that. But shamelessness is not a good thing either and I can tell you that far more people have been inspired to meaningful change not so much as a result of the things that they've done but because of the kind of person that they knew that behaviour reflected that they were. When somebody becomes uncomfortable with that, things really begin to change. Things really begin to change.

Elan: George, in one of your essays on your website called Self-Awakening In Times of Darkness, you write:

"Self-awakening generally happens in one of two ways. The first way is much less common. It occurs when a person is so totally swept away by great love and joy that they lose all sense of their smaller, wounded, guarded, well-defended 'false self'. Inhibitions melt away and they experience sublime ecstasy. But more commonly, it happens when circumstances deal such a fate blow that all one's learned ways of coping fail. This is an extraordinarily painful process and some don't survive it but those who do, even in the midst of their pain, find the light within and that's when real living truly begins for them."On the show we've talked a little bit about something called positive disintegration, the work of Casimir Dabrowski, a psychologist. This was his account of what you're saying here.

George: Right.

Elan: Where coming to a better place necessarily sometimes is very painful.

George: Right.

Elan: And some don't come out through the other side. But then here is the possibility that if one can endure this process and engage it that there's a possibility of living an even richer, deeper, more joyous life, that you're making space for a greater amount of joy and positive experience I think. Would you say that's correct?

George: Absolutely, yes. Couldn't have said it better myself.

Elan: The highest compliment.

George: And it does sound like he's saying the exact same thing, just in a different way.

Harrison: Actually I was thumbing through the book Character Disturbance because it has been some years since I read it. I read it when it came out. When was that? 2011 so 10 years ago now. There was a picture, the neurosis one.

George: Yes, the diagram.

Harrison: Yes, it was blurry. It's basically an arrow between neurosis and self-actualization/altruism. But then there's another arrow to character disturbance and character disturbance is on the same side of the spectrum as self-actualization and altruism and neurosis is on the opposite side. That immediately reminded me of Dabrowski because, just really shortly, the positive disintegration is his idea that there is a primitive integration of personality which must and does disintegrate in various forms through various neuroses and then that disintegration can be what he calls positive or negative. Negative would be suicide, psychosis, a total destruction in some way or other. A positive disintegration would be a reintegration on a higher level and the highest level would be something like what you write, an altruism, self-actualized in some way. He calls it secondary integration and it's that neurosis, it's that disintegration which is the primary means by which that happens, that that old integration has to be broken down and it has to fall apart in order to reintegrate on that higher level.

So when you have a personality structure, a person who never feels that organic shame of what they've done and even who they are if there's something that really is shame-worthy about it, they'll just remain that integrated personality and like the partner you described who really feels guilty every time they lose themselves and beat their partner, they keep just rebounding back to that personality structure. In Dabrowski's terms that would be disintegration and then right after that a reintegration at the same level. It doesn't go anywhere. That structure in a sense has to globally break down in order to recreate itself at a higher level.

So I think there's a lot to that, that that process is so important. That's why it's such a shame - no pun intended - that the mental health community totally dropped the ball all those years ago.

George: Yeah.

Harrison: What was another word for it?

Elan: The self-esteem movement.

Harrison: Yeah, the self-esteem movement. "You just have to feel good about yourself even if you're a crappy person."

George: Right, exactly. That's one of the commandments that I address in the new book about keeping that balanced sense of self-worth. Very few folks come to a point where they actually know where their worth comes from and what it really is. So we have these inflations that take on a narcissistic character.

Speaking of that, in the time that remains here, we're getting very short here...

Harrison: Yes.

George: ...I wanted to say that another unfortunate aspect of our times is that information about narcissism is out there everywhere. There's an expert around every corner and the fact is that character disturbance is a spectrum phenomenon and narcissism itself is a spectrum phenomenon. There are many, many different expressions of it and they're not the same. Their underlying dynamics are not the same.

So there are only a few general principles and rules and it saddens me that there's so much misinformation out there but there is a lot of it. And there's even some self-described psychopaths, malignant narcissists out there telling people essentially this: "I'm a person who can't care therefore I don't care about you. My purpose in life is to manipulate you and exploit you without any care or compunction and by the way, I have all the answers in this book that you need for your life." {laughter}

Elan: Exactly.

George: How anybody even entertains on the surface something as ridiculous as that I don't know, but that kind of stuff is out there. I'm not mentioning any names but I can think of two books right off the bat. So there's a lot out there but there's also a lot of misinformation and besides which, many times the pain in people's life is not aided by this information. It's only compounded. Folks in toxic relationships have this inherent cognitive dissonance and they really want to understand what's going on. But sometimes the understanding is in itself a burden. What we really need to do to wrest ourselves free is to carve a different path. All the understanding in the world won't necessarily get us there. It's the walk that gets us there. It's putting one foot in front of the other and taking a different course than we've been used to taking and experiencing the beautiful results of that.

So I always feel compelled whenever I give an interview to point to the fact that there's a whole lot out there but not a lot that will ultimately, meaningfully help change a person's life. Maybe that's another reason why I labour so long and hard on these things that I put out there. One of the four agreements that Ruiz talks about is being impeccable with your words, making sure that you're choosing them very carefully and that they really reflect something honest and true and bigger than you. They're not just words that sound really wonderful and make you sound great.

I remember the very first time that I listened to one famous radio commentator - I'm not mentioning his name - describing the purpose of certain elements of his program, he flatly stated to the audience, "The purpose is to make me look good because I'm here to sell myself. That's why you're tuning in. The purpose is all about me and me looking great and getting you to follow me and getting you to tell your friends to do the same. That's the purpose."

And that can be the purpose and if it is the purpose, it only helps perpetuate the problem. So we have to try to make it not the purpose. We have to try to make it about something bigger and more important than that.

Harrison: George, we know you're running out of time. You've got an engagement coming up really quick. On that, we're just going to have to wait for your next book to come out. We hope it's soon.

George: What a pleasant interview!

Harrison: It's been great, yeah. It's been fun. Had a great time.

Elan: Wonderful.

George: Yes.

Harrison: When the new book comes out let us know and we'll have you on to talk about it.

George: I definitely will. I'd love to have another conversation some time. There's tons of stuff we haven't covered.

Harrison: I wanted to talk a bit about psychopathy. I just mentioned it once. We didn't even get into it. We'll talk again. Thanks again so much and take care and good luck.

George: Thank you. Great to meet you.

Harrison: You too.

Elan: Thank you.

Adam: Bye George.

George: Take care. Bye-bye.

Reader Comments

SOTT Focus:Trump Supporters Gather in DC to Urge Congress Not to Certify Biden as President - UPDATES: Capitol Stormed, Shots Fired, Curfew Announced

Huge crowd waits to get through security, patriots climb trees to get better view Hundreds of thousands (possibly millions) of patriots have descended on Washington DC to show their support for...you state: In which case I challenge you to quit drunk-posting...

"amerikans have been liars and braggarts for 3 centuries". Daniel Boorstin

Today far worse---Twenge/Campbell: 'the narcissism epidemic'

Sarah Konrath, Abramsky, Twenge, etc

Right? ("Sure, RC, whatever you say." )

Anyway, instead, instead of from a grammar fascist, some grammar 'conservative' has requested that I note: Methinks ye meant 'altogether.'

RC

(BTW, I don't believe that English it B's first language, so my above is thoroughly unfair - and pure grammar nazi.)

Re your link: I swear, I've not heard this in DECADES! (That's one of the only Beatles albums I don't have. As I recall, it's probably, altogether, the least of them all together. )

RC

RC

(I shouldn't - but I do, love the stupid things.)

RC

I wish I could speak and think in another language - I still have hopes to do so someday.

NRN.

RC

Maybe Backer you have your dreams in one language and your nightmares in another.

Flaws are going to be revealed in OUR people tonight. Stay tuned. (Strange that NO Québec Media has covered these EVENTS since the STORY broke over 2 hours ago in Ontario)... strange

[Link]

Very significant times RIGHT NOW, explained on today's video and yesterday's.

[Link]

[Link]

Curfew begins in 9 hours.

I'd bet - no, I think I read? - that fecesbook et al. would shut down any listings of non PC / Can'tifa/BLM BM protests and I believe they have.

R.C.

P.s., Ain't that big Russian Army Kitty to the right a hoot? He looks like an overfed lynx, but where are the ears? I hope not cropped. But there appears to be plenty enough of evil and stupid for it to exist. [Link] (I should know. )

RC

PXVL: In exchange, I'll see your Baddest Girls and raise with American Girls, by Counting Crows. [Link] (A GREAT Album, too!) (Yep. You heard Sheryl Crow on the background vocals - I'm still in love with her, too.)

FWIW, I just heard a cut at around 3 minutes, probably to shorten it for that video. Pretty certain that a linked album track would be about 40 seconds longer. Sounded like they cut a break. Just heard another cut. Turns out they cut 40 seconds! Original: BEZELBUB! You've got to see the above biker girls video!

RC

RC

RC

Yeah, she's sexy. Prrrrr.....

Interesting how 'styles' come and go - what she's wearing you could probably see in some hip nightclub tonight. Meanwhile, yesterday, I wore blue jeans and an old USAF Olive Khaki Field Blouse; now I'm wearing navy cloth (I forget what it's called - 100% cotton slacks) pants and a Khaki cotton long sleeved shirt. I guess I was never a colorful bird. (I could drag out pictures of me from about age 14, it would be the same. It's a Southern thing, I guess. Bright colors are for the ladies.

R.C.

I got turned onto FM in the early 70's before SN was singing w/them. Peter Green & Jeremy Spencer on 'Then Play On' and Danny Kirwin on 'Kiln' House, and Bob Welch on 'Mystery to Me'. Kirwin & Welch in 'Future Games' (I'm big on guitarists) I liked it when they were more bluesy rather than the pop stuff that everyone associates FM with.

That video fooled me, too. They did a great job. I've never heard the song but Porter Waggoner damn sure looked like he did on the TV sets at my friends' houses.

We watched very little TV and my old man was burned out on the South - long story - but no country music around our house, no Porter Waggoner and No Damn Hee Haw! My parents (both born in 1931) were big on Pete Seeger, Joan Baez, Dylan, S&G et al.

RC

RC

to make a very long story short; i think it is completely irrelevant speaking of charachter disturbance and manipulative people unless also clearifying what periode of time one are speaking of. eg the periode of time between 1950 and 2020. outside of that time span people were mostly treated like cattle anyhow. (grandparents- and even parents stories).

It was a special interview with George Simon. He is our Ertugrul of the day. His character included humility, modesty, openness, compassion, sincerity, humor, desire to serve, desire to give the best of himself, courage to write and publish his book, desire to connect to a perceived higher power, etc. Truly a beautiful sensitive human being. He reminded me of Ibn Arabi’s direction to Ertugrul that everyone is a student. George wasn’t satisfied with the current paradigms of clinical psychology because they didn’t work, so he found methods that did work. The idea of acting the way you would if you thought and felt different is not intuitive, because the person can feel they are lying. However, action can evoke the thoughts and emotions that the therapist is opening the client to, because there are connections between heart, mind and body. Then he follows the guidance he is given to not publish his next book until he gets the spiritual component right.

Since one of our goals is to discover the truth of our reality, George is speaking about emotional truth. In our cancel culture society, there are only relative values depending on your point of view. George is saying there are values that are truth and love, they are commandments, they are laws of being. He is a conduit of this teaching as the frozen screen emphasized. His statement that our thinking is arrogant, as though we own the thought, was especially penetrating.

I thought his expression of what can be done, that we have only this moment when we can do anything was also special. Placing value on the moment with our friends and family, shows us where we need to focus more attention. I eagerly await his book to be finished. David

Great song.

RC

Drat it but the world's in even more of a mess than it was back then.

[Link]

Batard a forward type delay? "Linda!" I dunno. I give up.

J'viens juste de voir The view of just ends? Justice? I dunno.

ca sur Radio-Canada (A place near Big Sur, CA that plays only Rush?)

Ils vont vous remettre lockdown drette la, ouatche ben.

Lots of jokes I could do but won't

vont vous.. To you?

remit? 'drette la' Yiddish for 'dreck'.

ouatche ben. - Canadian Americanism meaning Whatcha been doing.

I tried, but wasn't much help other than Batard = Bastard & it wonders if the ending was Luxembougish.

RC

So I said to her, Batard Linda we use the expression bastard as a casual curse word, sort of rude but not too profane. then j'viens juste de voir ca sur Radio-Canada , I just saw this on CBC. Ils vont vous remettre lockdown They're going to put you under lockdown. drette la immediately. Drette (droit or droite) but that's how it's pronounced in Quebec, means straight or right so literally straight or right away. Ouatche ben watch well. We tend to use quite a few anglicisms colloquially.

I don't often get to express myself in my patois and I thought Linda might get a kick out of it too.

If she had any doubt I was from Qc. She won't after this.

Thank you!

RC

Good Luck!

RC

Just what one can expect from a psychologist. They have firsthand knowledge within their ranks.