In response to this sad situation, Diane Corcoran - a past President of the International Association for Near Death Studies (IANDS), and a veteran herself - has worked to raise awareness of NDEs with both veterans and care-givers. In recent years she had the idea to create a video to train veterans and their care providers about NDEs and their aftereffects.

You can find out more at a special page at the IANDS website devoted to the topic, "Impact of the Near-Death Experience on Combat Veterans":

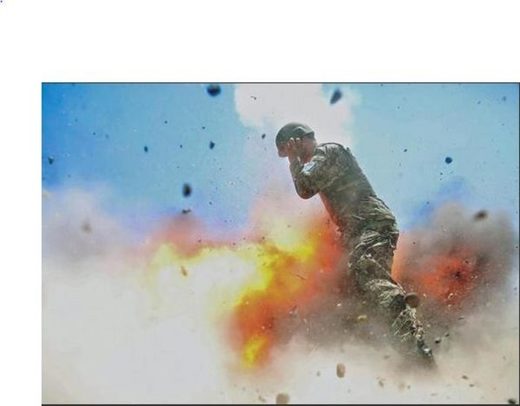

I came to believe that many soldiers were having near-death experiences as bombs exploded and gunfire nearly took their lives. But many were uncomfortable sharing what happened, and felt they had no one to talk to. But I knew they needed an outlet - someone to share their life-transforming experience with, who wouldn't be dismissive or think they were crazy.You can also hear more about the topic from both Corcoran, and near-death experiencer Tony Woody, in the following video of a discussion group titled "NDEs, Military Issues and Veteran's Video", recorded at the 2016 IANDS Conference:

While clinicians in most healthcare environments may have little knowledge of the NDE and its consequence, additional barriers exist in the military setting because the NDE and its consequences run counter to military culture.

There are many issues, and one of them relates to privacy and fear of disclosing the NDE to military commanders or health care providers. You may be asked to talk to your psychiatrist or psychologist in strict confidentiality, yet they may interpret the NDE as a mental health issue and put that into your record. When providers do not know about NDEs, they may think you have a mental illness and treat it with medication or other inappropriate intervention.

Commanders have great authority in the military and if you go to your commander and say, I need to talk to you privately about this experience I had, that could be the end of your career. It's a culture in which consequences can happen quickly, and because of a lack of knowledge about NDEs, it may end a soldier's career. One soldier told me that the minute he told his nurse about his experience, he was sedated for three days and then sent to see a psychiatrist immediately. They thought he was crazy. In fact, people with NDEs are not mentally ill, but may benefit from supportive counseling to help them integrate the experience. Currently, providers are not prepared to offer such counseling.

The military depends on structure and discipline, and this often runs counter to common aftereffects of NDEs. Common effects include changed attitudes and beliefs, such as a philosophy of nonviolence, extreme appreciation of nature, high empathy and affection, and different priorities for time management.

The aftereffects of an NDE aren't always conducive to staying in the military, as NDErs may become altruistic and less rule based. The commander of a unit, a West Point graduate with a lot of experience, told me that since his NDE, he was having trouble with command and discipline issues.

All I really want to do is put my arm around these young soldiers, and say we're going to work it out. And I have to tell them that it may not work out for them in the military, so they may need to find another place that will value their change in attitude.

Comment: For more on near death experiences see: