|

| ©Unknown |

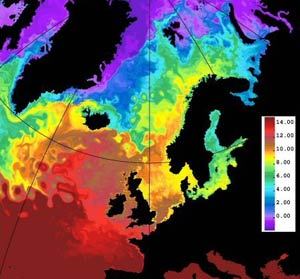

The Atlantic Ocean "conveyor belt" that carries warm water north from the tropics has weakened by 30 per cent in 12 years, scientists have discovered. The findings, from the National Oceanography Centre in Southampton, give the strongest indication yet that Europe's central heating system is breaking down under the impact of global warming.

Scientists have long predicted that melting ice caps could disrupt the currents that keep Britain at least 5C (40F) warmer than it should be, but the new research suggests that this is already under way. It points to a cooling of 1C over the next decade or two, and an even deeper freeze could follow if the Gulf Stream system were to shut down altogether.

The British Isles lie on the same latitude as Labrador on the East Coast of Canada, and are protected from a similarly icy climate by the Atlantic conveyor belt, which carries a million billion watts of heat. Although oceanographers still think it unlikely that the currents will stop completely, this could reduce average temperatures by between 4C and 6C in as little as 20 years, far outweighing any increase predicted as a result of global warming.

Even a lesser fall in temperatures could mean that Britain gets colder even as the rest of the world warms up, and would severely disrupt the Government's plans for mitigating the effects of climate change.

The Gulf Stream begins in the Gulf of Mexico and carries warm water north and east, through the straits of Florida and across the North Atlantic. Halfway across the ocean, it branches into two, with one current flowing south towards Africa and another drifting towards northern Europe. By the time the northern current reaches the Arctic, its waters have become colder and more saline, causing them to sink. A vast undersea river of cold water then flows back towards the Gulf.

Global warming is predicted to disrupt this process, as extra freshwater from melting ice caps reduces the salinity of the Arctic waters, stopping it from sinking and breaking the circuit. The Southampton team measured current flow across a latitude of 250N. The original Gulf Stream, cold water returning from the Arctic, and the southern branch of warm water all cross this line stretching from North Africa to the Bahamas. Measurements taken last year were compared with data collected in 1957, 1981, 1992 and 1998.

The results, published today in Nature, show that the outward flow of the Gulf Stream has not changed, but the strength of the cold water returning from the Arctic has fallen by 30 per cent since 1992. Over the same period, the flow of warm water branching off towards Africa has increased by 30 per cent. This suggests that the warm waters are being diverted away from Europe.

Meric Srokosz, of the Natural Environment Research Council, which funded the work, said: "If it is persistent or there is a further decline then, yes, it would have an impact on the climate. The models suggest that if the change is persistent we might see the order of a 1C drop in temperature here over a decade or two."

It remains possible that flows change annually or seasonally and that the 1992 and 2004 data were aberrations. A project is under way to monitor Atlantic currents for four years.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter