© GARY S CHAPMAN/GETTY IMAGESCompasses are very useful, but, researchers suggest, the best one might reside somewhere in your brain.

The Earth's magnetic field is faint, yet creatures from birds and bees to lobsters and bacteria have been shown to detect its dull pull.

Now, after half a century of looking, scientists have reported the most convincing evidence yet to suggest humans, too, share this ability.The mysteries surrounding magnetoreception, as it is called, abound. It makes sense for globetrotting migratory birds and turtles to have an in-built compass, but it is far less obvious why cows might need one to

orient their bodies along the magnetic field lines when grazing, or dogs to point

north or south when defecating.

The first inklings that humans might have an internal compass came from studies by Robin Baker at the University of Manchester in the UK. In 1980, he reported that if he blindfolded students and transported them out of town, they could almost always point towards the quadrant of their starting point, but they lost this ability if a bar magnet was strapped to their heads. Subsequent attempts to replicate the findings failed, however.

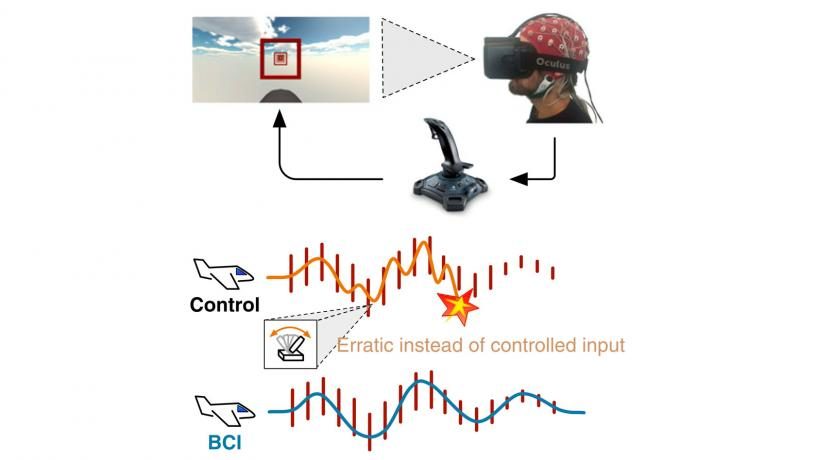

Biophysicist Joe Kirschvink, then at Princeton University in the US, is one person whose replication experiments fizzled in the 1980s. But three decades later, and now at the California Institute of Technology, he and colleagues came up with a better way of testing whether humans have an internal compass.

Instead of asking his subjects for a conscious, behavioural response to changes in magnetic field, he decided to ask their brains directly.

Comment: The idea behind training one's brain is certainly valuable, but much of what is on offer in the commercial marketplace is little more than hype. If you really want to 'train your brain', whether it be to improve intelligence, be more creative, have greater attention or be less emotionally reactive, chances are you're not going to get this from a phone app or computer software. Exercise, meditation, targeted learning (like language learning), better nutrition - these are the things that science is uncovering to be truly helpful in improving brain performance, not gimmicky 'brain games'.

See also: