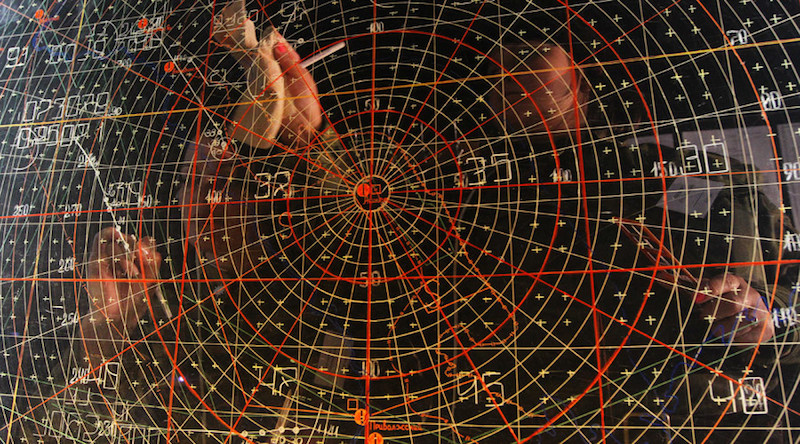

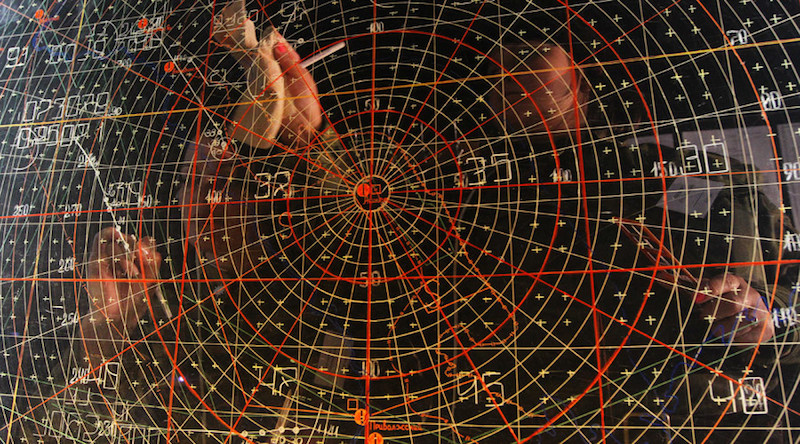

© © Mikhail Fomichev / RIA NovostiRadio-photonic technology to be applied in radio astronomy, radio detection and ranging, optical fiber and mobile communications

It is expected to open a new era of light and precise radar electronics for systems where weight is critical, such as

drones and satellites.

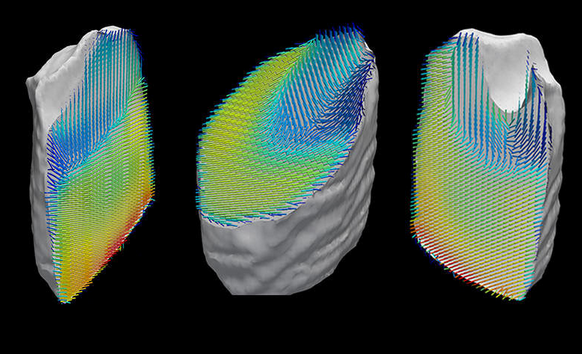

The radio-photonic radar system of the future will be

based on active radio-optical phased array (Russian abbreviation: ROFAR) technology being developed now by

Radio-Electronic Technologies Concern (KRET), an integral part of the Rostech state corporation.

"The KRET has launched radio-photonic laboratory research to create ROFAR to be

integrated on next generation radar systems, which is expected to deliver breakthrough performance characteristics to radiolocation stations," Igor Nasenkov, deputy general director of KRET, told RIA Novosti during the Dubai Airshow 2015.

Work on ROFAR involves the creation of a specific laboratory complex within KRET. It will develop a

universal technology to be later integrated into various next generation electronic systems. Nasenkov specified that the 4.5-year ROFAR program will be fulfilled on time, adding a full-scale specimen is expected to be test-launched "by 2018."