© American Chemical SocietyScientists have developed a bone grafting material made out of sea urchin spines.

More than 2 million procedures every year take place around the world to heal bone fractures and defects from trauma or disease, making bone the second most commonly transplanted tissue after blood. To help improve the outcomes of these surgeries, scientists have developed a new grafting material from sea urchin spines. They report their degradable bone scaffold, which they tested in animals, in the journal ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

Physicians have various approaches at hand to treat bone defects: Replacement material can come from a patient's own body, donated tissue, or a synthetic or naturally derived product. All of these methods, however, have limitations. For example,

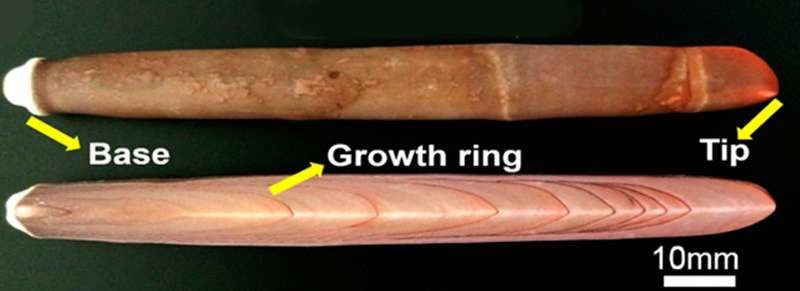

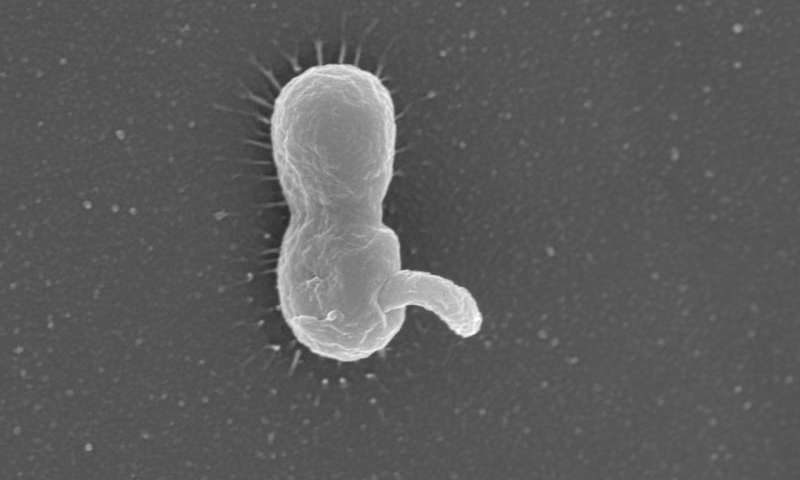

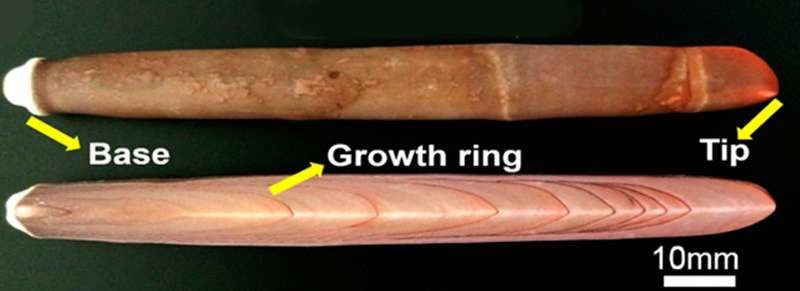

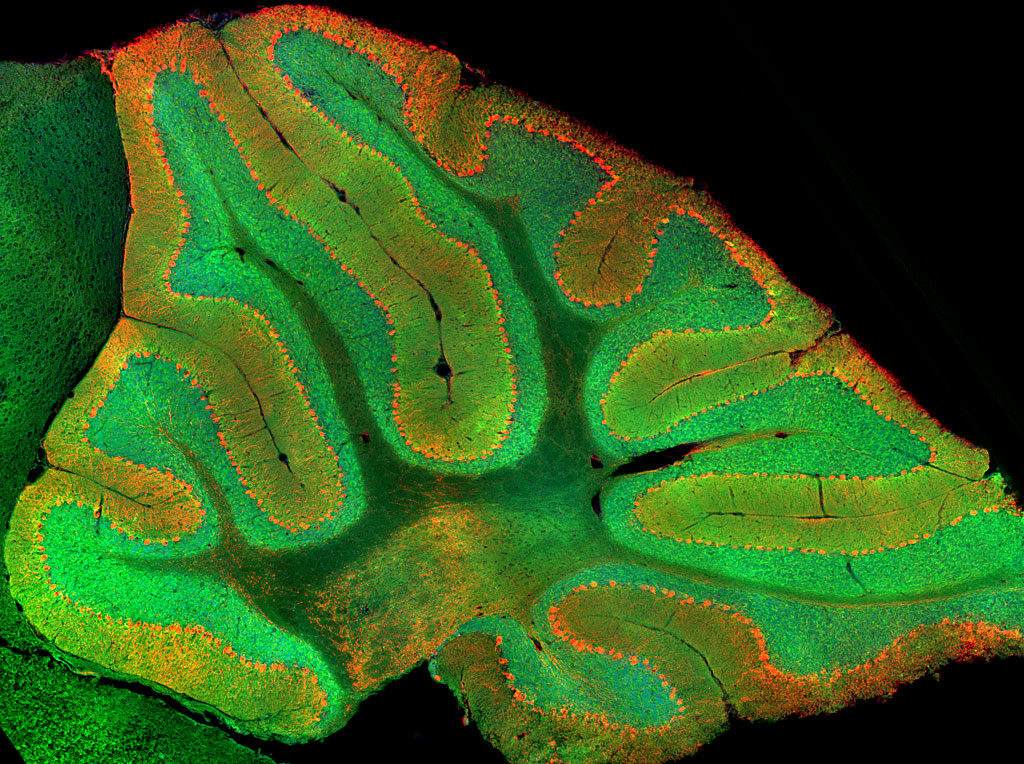

current bioceramics, such as hydroxyapatite, that have been used as scaffolds for bone repair tend to be weak and brittle, which can lead to pieces breaking off. These pieces can then move into adjacent soft tissue, causing inflammation. Recent studies have shown that biological materials, such as sea urchin spines, have promise as bone scaffolds because of their porosity and strength. Xing Zhang, Zheng Guo, Yue Zhu and colleagues wanted to test this idea in more detail.

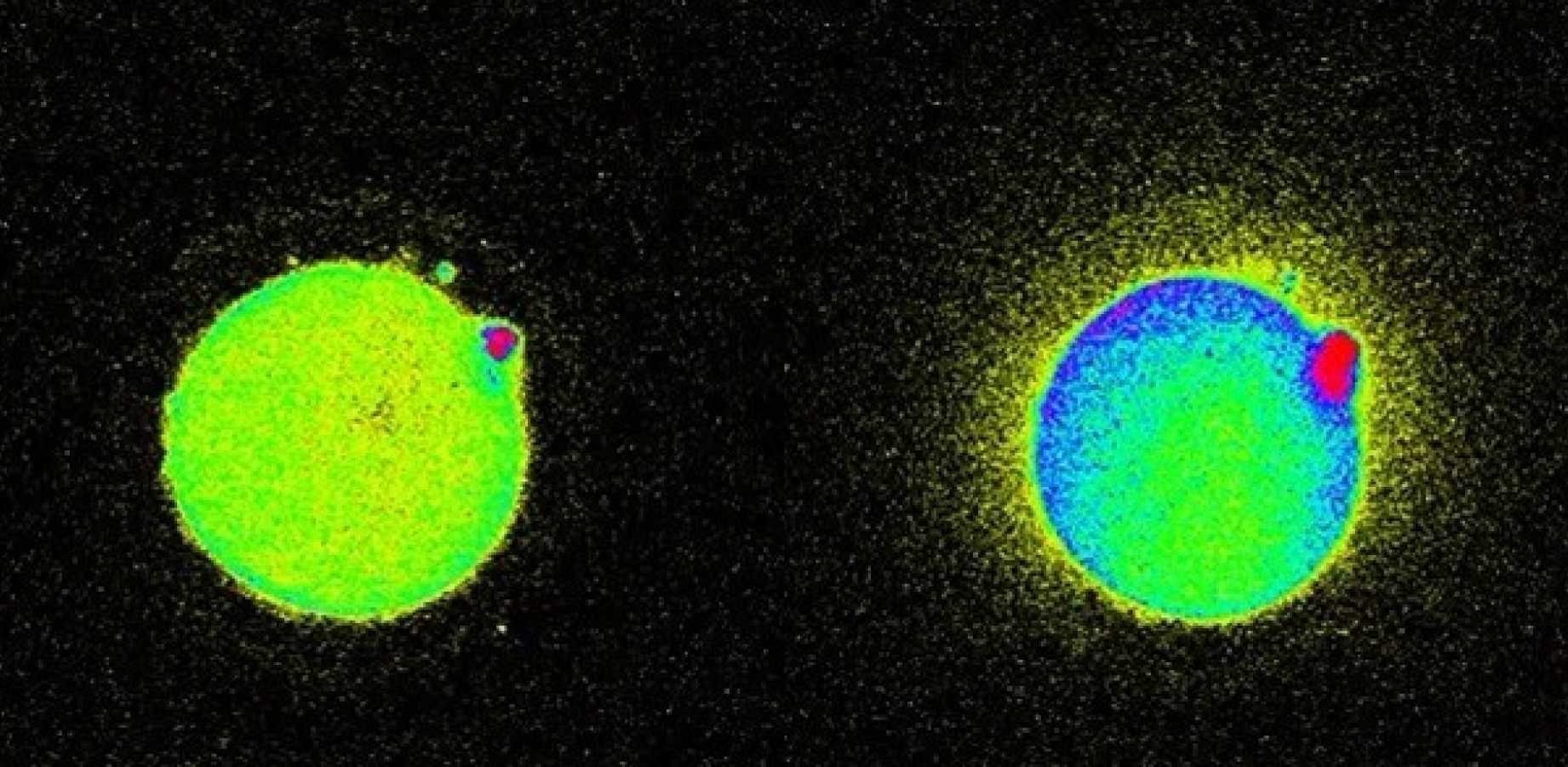

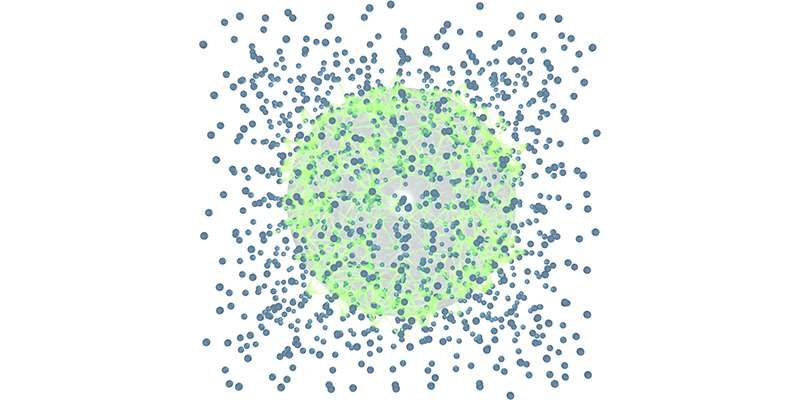

Using a hydrothermal reaction, the researchers converted sea urchin spines to biodegradable magnesium-substituted tricalcium phosphate scaffolds while maintaining the spines' original interconnected, porous structure. Unlike hydroxyapatite, the scaffolds made from sea urchin spines could be cut and drilled to a specified shape and size. Testing on rabbits and beagles showed that

bone cells and nutrients could flow through the pores and promote

bone formation. Also, the scaffold degraded easily as it was replaced by the new growth. The researchers say their findings could inspire the design of new lightweight materials for repairing bones.

Comment: Other researchers agree: