The Gurandgi Munjie group is revitalizing native crops once cultivated by Aboriginal Australians, baking new bread with forgotten flours.

At Cuddie Falls, in New South Wales, Archeologists found evidence of this in the form of an ancient grinding stone that was used to turn grass seeds into flour.

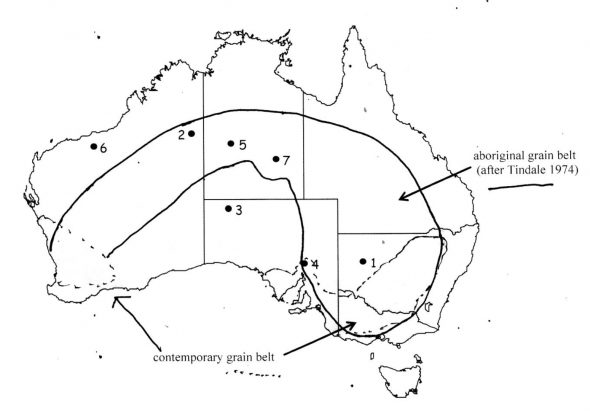

"Environmentally it's a pretty good deal," says Pascoe of growing these native crops. This map gives an indication of how much we can learn from Aboriginal grain production. Norman Tindale documented that Aboriginal grain harvests occurred over most of the Australian continent but contemporary grain areas make up less than a quarter of that area.

This was and is an incredible human response to the difficulties of fostering economic, cultural and social policies. It may be unique in its longevity but also in its ability to flourish without resort to war.

Australia's reluctance to acknowledge what was lost can be witnessed in our ignorance of the birth of baking, the gold standard of economic achievement.

Comment: By most measures human's reliance on agriculture was a fairly deleterious decision, although it may have arisen at a time where it was a necessity for survival.

Why is this? Is it a malicious refusal to recognize the economic triumphs of the people from whom the land was taken or a simple culture of forgetting fostered by the bedazzlement of Australian resources and opportunities?

If we could rid ourselves of the myth of low Aboriginal achievement and nomadic habits, we might move toward a greater appreciation of our land.

We might begin to wonder about the grains that explorer Thomas Mitchell saw being harvested in the 1830s, and the yam daisy monoculture he saw stretching to the horizon of his 'Australia Felix', the early name given to western Victoria.

These crops must have been grown without pesticides and chemical fertilisers and in harmony with the climate; surely they are worthy of our investigation.

If you search for Australian research into yam daisies you inevitably come across, Beth Gott, an honorary research fellow at Monash University.

She has almost single-handedly led the interest in this wonderful plant. Inspired by her work, a Landcare group and Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in East Gippsland have begun field trials into the staple of the southern Aboriginal economies.

Similarly, the fish traps at Brewarrina seen by Mitchell and other explorers created economic conditions that allowed the people to live in semi-sedentary villages of over 1000 people; Mitchell marveled not just at the villages' size but also their comfort and elegance.

Since Mitchell's report, however, you will look in vain for later reference to the Brewarrina fish traps even though some archaeologists have speculated that they maybe 40,000 years old and as such the oldest human construction on the planet.

Even if you accept the more common age of 15,000 years, these structures are still amongst the world's first. Until recently, the sole publication about them was a 50-page book published in Brewarrina in 1976.

When we eventually acknowledge the food plants adapted to Australian conditions and domesticated by Aboriginal people, let's hope we don't just celebrate them every 'Baker's holiday' but recognize the intellectual property Aboriginal Australia has vested in them.

Comment: See also: