Immediate Gratification

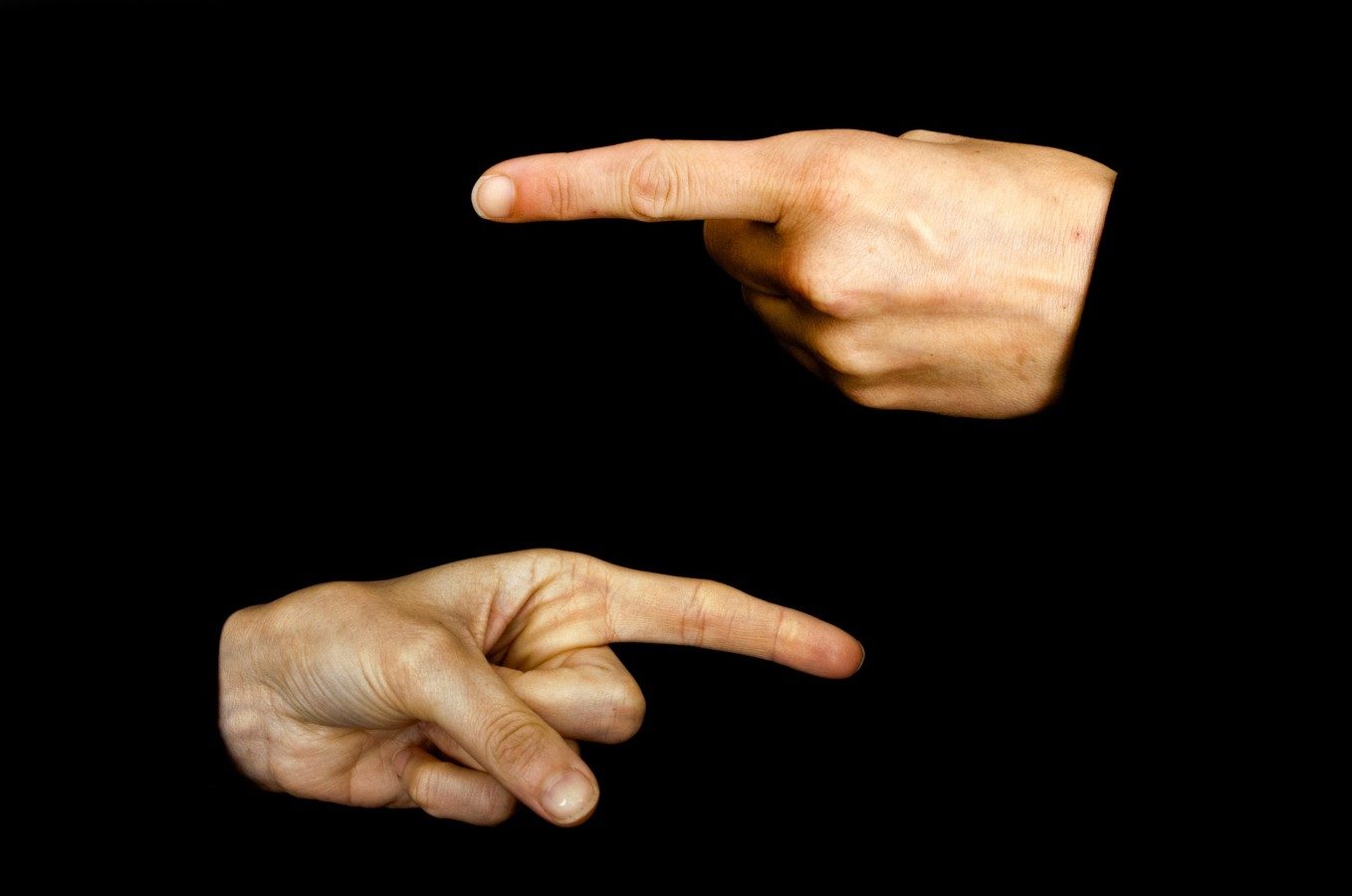

The sheer accessibility of information today is a main cause of the chaos. Our ability to ping-pong between current events, health news, and constant entertainment all while simultaneously working and eating our dinner is incredible. We have perfected the art of immediate gratification: if you cannot find something this instant that changes your mood, answers your question, or takes your mind off whatever you are avoiding, you are likely not searching hard enough. The literal world is now at your fingertips, for better or for worse.

The majority of adults in the United States spend over 10 hours per day attached to media in some way.1 This instantaneous access to anything we could possibly need has infiltrated our desires, behaviors, and even our goals. It slinks into our heads and takes root, creating a deep belief that pleasure is always within reach. The downside is that when pleasure suddenly becomes elusive, no one understands why.

Immediate gratification works very well to create a sense of happiness, until it stops working. Inevitably, we cannot always have everything we want. Since we have become masters at training ourselves to believe in the justice of immediate gratification, when it no longer works it is shocking. Interestingly, one of the most readily available excuses we use when this happens is "it wasn't my fault." Being denied immediate gratification has become too painful for us, resulting in an aversion to examining whether our expectations and behavior could have contributed to this outcome in the first place.

Fault Finding as a Coping Skill

When someone is used to getting what they want most of the time, it very easily turns into an expected pattern. The line between wants and needs becomes blurry, often dissipating completely into the fog of "the way it used to be." Remember when you had to wait hours, and sometimes days, to receive an answer from someone? How archaic.

Now that instantaneous satisfaction has become the norm, when conflict or dissonance arises it can become atomic in its destruction. The ability to disagree respectfully has become almost non-existent. Any type of disagreement tends to be viewed with complete astonishment: When the world is at your fingertips, how can there be conflicting points of view? After all, if you look hard enough you will always find someone with the same point of view.

Fault finding quickly follows on the heels of not getting what is desired. As a society, we are accustomed to answers. When something as critical as delayed gratification occurs, it is natural to demand why. Regrettably, although the answer many times lies within our own choices and behaviors, we often seek external reasons for our denial of satisfaction.

In many ways, it is protective of a fragile self to deny any wrongdoing. Admitting a bad decision can be a tremendous blow to self-worth, particularly when it will most likely be immediately attacked by the hordes of individuals who have never done anything wrong. Frosting over mistakes and denying their existence is a much safer, albeit disingenuous, route.

Toxic Outcomes

The pleasure principle (avoidance of pain and pursuit of pleasure) has been posited to drive much of human behavior.2 Modern society strongly facilitates the pursuit of pleasure but provides minimal guidance for how to handle a failure in accessing it. What happens when suddenly we realize pleasure has eluded us? The toxicity produced from these circumstances is poisonous to our well-being.

Our reduced awareness of how behaviors affect outcomes is directly related to the instant access we have to an overload of information. If you are feeling discomfort at a recent social interaction, or experiencing angst related to something you may have said to a loved one, a quick and painless fix is distraction. Brush it off, bury it in the sand, and be done with it. Society will help cover it up by bombarding you with the next best thing in a continuous stream of information and flashing lights.

Fast-paced living makes denial effortless. There is no longer time to sit down and hash out differences until a compromise is reached. There is too much supporting information for both viewpoints to "agree to disagree." The quickest means to an end is blitzing any naysayers with your opinion, leaving behind only quiet and agreeable rubble.

When energy is being expended at a previously unheard-of rate, survival depends on conserving it where possible. Full speed ahead has been the motto for decades, despite the knowledge that it is likely the cause of too many health issues to track. Anyone who gets in the way is quickly swept to the side, and taking accountability for how these behaviors are creating our own toxic outcomes is far too dangerous of a game to play.

Accountability as an Antidote

The antidote to this slow poison that is rotting our connections with others lies in the power of pushing back. There is immense strength in stepping out on a limb to permit vulnerability. Admitting to imperfection is the first step in opening horizons and learning new ways of restoration. Although it comes with colossal risk, accountability is a passage to recovery.

We have seen the influence of one person refusing to move, one person sharing their dream, or one person never giving up. Reversing the tide of self-serving pleasure seeking can be as simple as acknowledging we are all broken in some way. Being able to say "it was me," reaching out to those we have knowingly hurt, and accepting that what makes us different is the glue that holds us together and can reduce some of the chaos.

Accountability is not a dirty word. It paves the way to learn new skills and build deeper connections with others. By admitting to our own faults and mistakes, we jettison the victim role and take back the power to change.

References

The Nielsen Total Audience Report Q3 2018. (2019). https://www.nielsen.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2019/04/q3-2018-total-audience-report.pdf.

Freud, S., & Jones, E. (Ed.). (1922). International psychoanalytical library: Vol. 4. Beyond the pleasure principle (C. J. M. Hubback, Trans.). The International Psycho-Analytical Press. https://doi.org/10.1037/11189-000

I need more time.

If I had more time, I could make more money.

If I had more money, I could make more time.

ned,

out