© SOTT

Are killers born or made? Depending on who you ask, you'll get a variety of responses: all humans are good - it's only the 'environment' or 'society' that makes them do bad things; anyone who engages in murder must be a cold-blooded psychopath, born to kill. But simple explanations come from simple minds. It's not a matter of either/or. Some people are born that way, like psychopaths. Some have the strength of character to resist the impulse to conform. But most people are somewhere in between, easily swayed to do the will of whoever is giving the orders.

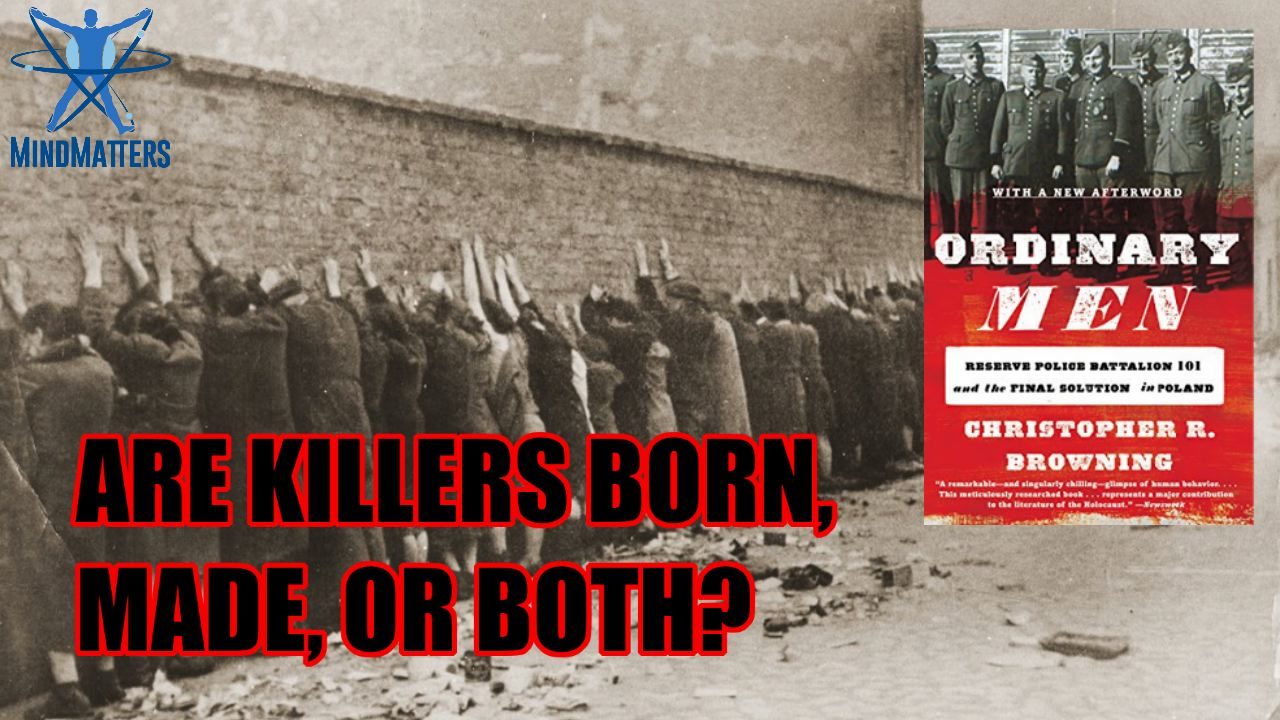

On today's MindMatters we delve into the hellish depths of World War II and Christopher Browning's excellent but disturbing book,

Ordinary Men: Reserve Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland. His research confirms what studies like those of Milgram demonstrated in the lab: normal people show a spectrum of responses to the influence of authority. A small minority are very willing to inflict harm to others. Another small minority refuses. But the vast majority go along, even if it makes them sick to the stomach and traumatized for life.

Running Time: 01:24:17

Download: MP3 — 112 MB

Here's the transcript of the show:Corey: Hello everyone and welcome back to Mind Matters. On today's show we're going to be discussing Christopher Browning's book

Ordinary Men-Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland. Like a lot of people, we were turned onto this book by Jordan Peterson because he recommends it as a way of seeing what ordinary people are capable of and what we, presumably, would also be capable of, given peer pressure, conformity and hysteria and all of the different things that were going on at the time of Nazi Germany.

So we've been reading this book for the past week and this is what Christopher Browning writes about the questions, methods and materials he had for writing this book. He writes,

"

How had the Germans organized and carried out the destruction of this widespread Jewish population and where had they found the manpower during this pivotal year of the war for such an astounding logistical achievement in mass murder? The personnel of the death camps was quite minimal but the manpower needed to clear the smaller ghettos, to round up and either deport or shoot the bulk of Polish Jewry was not. Why did most men in this Reserve Police Battalion 101 become killers while only a minority of perhaps 10% and certainly no more than 20%, did not?Well the search for the answers to these questions led me to the town of Ludwigsburg near Stuttgart. Here is located the central agency for the state administrations of justice, the Federal Republic of Germany's office for coordinating the investigation of Nazi crimes. I was working through their extensive collection of indictments and judgments for virtually every German trial of Nazi crimes committed against the Jews of Poland, when I first encountered the indictment concerning Reserve Police Battalion 101, a unit of the Germany Order police.Though I had been studying archival documents and court records of the holocaust for nearly 20 years, the impact this indictment had upon me was singularly powerful and disturbing. Never before had I encountered the issue of choice so dramatically framed by the course of events and so openly discussed by at least some of the perpetrators. Never before had I seen the monstrous deeds of the holocaust so starkly juxtaposed with the human faces of the killers.In writing about this police battalion therefore, I have depended heavily upon the judicial interrogations of some 125 men, conducted in the 1960s."

He uses the words "powerful" and "disturbing" and I think that is exactly the impact that this impact has on you. It's not an easy read by any means, largely the German phrases. You're being forced into a situation where you can easily empathize with the individuals who are going through this indoctrination basically. They're from working class areas. They are mostly from Hamburg I think. He said about 60-70% of the individuals were from Hamburg, Germany. They weren't scholars. They were just policemen and they were used and utilized to carry out this mass destruction of human life.

Harrison: Maybe a bit more about the individuals involved because, like you said, this was a battalion in the order police and at this time in the war, the Nazis had expanded east through Poland and into Russia. That's where all the regular troops were, all of the commissioned officers and people who were drafted. That's where the major fighting force of the Reich was, on the front lines. So for these battalions they had to find people to enter this police force and the only people who were left were middle-aged men and those that were unfit or too old to be in the regular army.

So these battalions were largely made up of middle-aged men, business owners. The majority of them were Nazi party members but they often weren't SS members. They were just people who had joined the party in the last 10 years or so but weren't super ideological or high ranking or anything like that. These were pretty much the leftovers of the German males in the population that were drafted into this new police force. They essentially thought they were just going to be a police force.

So what would happen was, as the Germans moved east they now had all of this occupied territory. So the Germans would put in new German civil administrations to administer these new cities. The Germans would be in charge but now they would be responsible for holding the land behind the front lines, taking care of policing for partisan behaviour, counter-revolutionaries, stuff like that and of course the Jewish populations. But for the people who were drafted into this police force, they were under the impression presumably, that they were going to be just policing the area. Then when they got there and received their orders it turned out to be a lot more than that. These guys essentially formed death squads.

A bit more on the background. You mentioned he found these documents. The documents he primarily uses are the testimonies and interrogations of a lot of lot of these men but also some official records, like memos back and forth between the leadership of the battalions and their higher-ups in either the government or the SS. Some of those make for pretty stark reading too. Then my last point on that intro is that you mentioned just how disturbing it is. This is a very disturbing book to read. It's not something to read if you're light-hearted at all because it goes into all of the details of what happened. It's pretty amazing.

The first thing I think of when I read interrogations or testimony, you always have to be somewhat skeptical of what's going on, and he is, because in a lot of cases you might get coerced or evasive testimony. So figuring out the exact truth of the matter can be a difficult job when you're looking at evidence of this sort. But I think he does a pretty good job, just from what I can tell, from my own judgment. He does a pretty good job of trying to find where the most accurate version of events is within all of this sometimes conflicting evidence. But oftentimes if you read the footnotes or just in the course of the chapters, you see that oftentimes the testimonies align in certain ways to give an accurate picture of what was going on.

Maybe we can give an overview of what these guys were doing. Like I said, they were going into the newly acquired territories and they were responsible, in any given village or maybe even some larger cities, for going in and resettling the Jewish populations. It wasn't always just the Jewish populations. It was native Poles as well and gypsies, rounding them all up and, as far as these guys new before actually doing it, putting them on trains and resettling them further east.

So that's what they thought they were doing. That was partially what they were doing, but when it came down to it, what their job actually was, was to go into the ghettos or mixed cities that might be 30-50% Jewish, round up the Jewish population, oftentimes in the marketplace or in a town square or a stadium-type building or any type of large space where people could be rounded up. They'd first go to their homes and forcefully take them out of their homes to this place. At first they were not given the order, but it was made clear that there was no use for the old, the weak, oftentimes the women and the infants. So at first these guys thought, "Okay, there's no need for them" so they would let them go or leave them. Then they said, "No, you have to bring everyone" so they'd bring everyone. "Oh, but we don't need the children".

It became clear very soon that they were to shoot the infants and the old and weak on the spot. So that's what a lot of them did. Going into a home, if there was a family with an elderly person and an infant and a weak mother, they were to shoot them there on the spot, execute them and then take the men. A lot of the Germans that were in these squads couldn't kill the children, even then, so they'd often let the children go with their mothers and they'd be told off by their superiors once all the people were gathered. "You have to be more strict. You can't let these people come through."

So that was now standard operating procedure for all of these operations, all the "Jewish actions", I think they called them. They immediately killed the old, the weak and the children. Then once they had them all corralled into an area, oftentimes they'd be forced to sit for hours on a hot summer day and not given any food or water and then they would oftentimes pick the most fit, young and healthy and they would be sent off to a work camp. Everyone else would oftentimes be walked out to the forest outside of the village or town and over the course of the day, into the evening, just put before firing squads out in the forest and killed in groups of 20 to 30.

With that said, I want to read an example of one of the orders that was given. This was after a meeting between some of the heads of various departments, like the Order Police, with the top brass. Two days after a meeting on July 11, 1941, I believe, Colonel Montua of the Police Regiment Center, which included Police Battalions 316 and 322 - the majority of the book is about Police Battalion 101 - issued the following order:

"

Confidential.Number 1, by order of the higher SS and police leader, all male Jews between the ages of 17 and 45 convicted as plunderers, are to be shot according to martial law. The shootings are to take place away from cities, villages and thoroughfares. The graves are to be leveled in such a way that no pilgrimage site can arise. I forbid photographing and the permitting of spectators at the executions. Executions and gravesites are not to be made known.Number 2, the battalion and company commanders are especially to provide for the spiritual care of the men who participate in this action. The impressions of the day are to be blotted out through the holding of social events in the evenings. Furthermore, the men are to be instructed continuously about the political necessity of the measures."

So that's the order that the top guys received. So they go and commit one of these actions. This I thought was really interesting. This was a report that was sent back from the regional commissioner of Slutsk which was a town near Minsk in what's now Belarus. Here are a couple of extracts from the report that he sent back to his superiors. This was from that regional commissioner to the general commissioner in Minsk concerning Jewish action, written on October 30, 1941. I'll start reading and then maybe just jump ahead to some bits.

"

In reference to my telephone report of October 27, 1941, I submit the following to you in writing. On the morning of October 27 about 8:00 a first lieutenant of Police Battalion 11 from Kovno, Lithuania appeared. He introduced himself as the adjutant of the battalion commander of the security police. The first lieutenant declared that the police battalion had been assigned the task of carrying out the liquidation of all Jews in the city of Slutsk within two days. The battalion commander was approaching with a force of four companies, two of them Lithuanian auxiliaries and the action had to begin immediately.I thereupon answered the first lieutenant that in any case I first of all had to discuss the action with the commander. About one-half hour later the police battalion arrived in Slutsk. As requested, the discussion with the battalion commander then took place immediately after his arrival. I explained first of all to the commander that it would scarcely be possible to carry out the action without prior preparation because all the Jews had been sent to work and there would be frightful confusion. At the very least he was obligated to give one day's notice.I then asked him to postpone the action for one day. He nonetheless rejected this noting that he had to carry out actions in the cities all around and only two days were available for Slutsk. At the end of these two days Slutsk had to be absolutely free of Jews. I immediately lodged the sharpest protest against this, in which I emphasized that a liquidation of the Jews could not take place arbitrarily, that the larger portion of Jews still present in the city consisted of craftsmen and their families. One simply could not do without the Jewish craftsmen because they were indispensable for the maintenance of the economy. Furthermore, I referred to the fact that white Russian craftsmen were, so to say, utterly unavailable, that therefore all vital enterprises would be paralyzed with a single blow if all Jews were liquidated.At the conclusion of our discussion I mentioned that the craftsmen and specialists insofar as they were indispensable had identification on hand and that these Jews were not to be taken out of the workshops. It was further agreed that all Jews still in the city, especially the craftsmen's families whom I also did not want to have liquidated, should first of all be brought to the ghetto for the purpose of sorting. Two of my officials were to be authorized to carry out the sorting. The commander in no way opposed my position, so in good faith I believed that the action would therefore be carried out accordingly."

So it goes on and he writes that this Lithuanian guy totally disregarded his order and was rounding up everyone. They almost got into a shooting match with the Lithuanians. We'll get into them in a while.

The guys who had come in to carry out this action were rounding everyone up. The commissioner was going around with his guys trying to pick out some Jews that they wanted to keep, that they didn't want killed. It was just back and forth. There was shooting in the streets and it was a complete disaster. So here you have this one guy who's got common sense and a little bit of a heart, not very much given the situation, but he's saying, "No, you're going to absolutely wreck the economy. All of these people are needed."

So what happened after this was that they took out all of these Jewish craftsmen. He managed to save a few of them and immediately all of the factories can't work. None of the stores have full capability. They lose all of the master craftsmen who can't be replaced so everything falls apart.

These actions were not only destructive but self-destructive too because these people were integral in the economy and the civic life of these places and they were torn out. What happens then? Everything falls apart. Just reading this one report gives you an idea of the variety of reactions and world views and points of view of the different individuals involved. This will come out too when we look at the individuals in the Reserve Battalion 101 because they weren't all cookie-cutter Nazis. They were a variety of different types of people involved. They were all individuals. Some of them had similar reactions. Some of them had other reactions.

With that said, were there any specifics about what these guys were actually doing that you wanted to bring up Corey?

Corey: I did want to touch on one individual, now that we're talking about the Reserve Battalion 101. Major Wilhelm Trapp, was the commander of this battalion during the time that Christopher Brown is really covering in this book. A large part of the book is devoted to the history leading up to the Final Solution and how it was carried out in Poland and then discussing the indictments. You get to know the characters around July to October of 1942 when a lot of the action takes place and how things began to escalate in terms of turning a crew of people who were mostly uneducated laborers, some skilled craftsmen from Hamburg into a really hardened killing machine that wouldn't flinch at the murder of children and women.

One important person in that regard is the commander, Major Wilhelm Trapp who was an Iron Cross recipient during WWI. He was largely considered a war hero. He was 53 at this time and he was referred to by his subordinates as Papa Trapp. That was the term of endearment that was given to him. He wasn't in the SS but he was a Nazi party member. But he wasn't considered cut from the right cloth to be part of the SS. Obviously he had authority and he had a war record. He was a career policeman following WWI and all the civic unrest that followed.

But he was still relatively normal. He still had what you would probably consider a normal emotional reaction to the events that led up to an entire chapter in this book, chapter five I believe it was, which was the massacre at Józefów. That's a town in Poland where in the early morning of July13th the reserve battalion was roused and told that they were going to be given a very interesting task. Major Trapp came out and tried to sell everyone on this idea that the Jews had instigated a war against Germany and so they had to escalate their efforts and begin wholesale murder of every Jew in this town.

But he at the same time gave these police officers the opportunity that if they did not feel like they were up to the task that they could abandon ship basically. They could go and do guard duty or anything else instead of becoming part of this killing team. They had been given orders. They were told exactly where to point the bayonet on the rifle in order to guarantee a kill with one bullet. Almost no one was capable of doing this, for whatever reason. So it was just horrendous. A lot of them didn't realize at the time how horrendous and evil it was. One individual stood forward when given the opportunity not to engage in the actual killing and he was lambasted by his superior. He was ripping into him, calling him a shit bag and a coward. But Major Trapp upheld his decision and then I think it was a very small number then followed and, under the protection of the commander, were allowed to excuse themselves from the killing.

That didn't mean that anybody was actually any good at it either. An enormous amount of alcohol was required after the first day in order to just drown their sorrows. They were even told, "Don't talk about any of this. Don't discuss it." But they didn't need to be told that. They had already, through being covered with gore from the murder of old men, women and children, many of them tried to find other ways to escape. They would intentionally miss when they were shooting. They would run off and pretend like they were doing some other duty, trying to look busy.

But in every testimony it was just the pure instinctive revulsion at it. It wasn't an ethical revulsion to what they were doing. On a biological level, they were incapable of doing that without becoming sick. Time after time you read about how they were so nauseous and disgusted with it but you don't ever get a sense that they felt that it was fundamentally something that they could never live with themselves for doing.

Harrison: Yeah. He makes the point that very few cited any kind of ethical considerations. He does quote a few, like one who said, "No, this is just something I can't do." Another one said, "Where I'm from I'm a business owner and I know a lot of Jews and I can't do this." So there were a few. But like you said, for most of them it was purely instinctual. So even in that first moment where Trapp offers them a way out to start out with, only a handful took him up on the offer and Browning points out that even this was just an instinctual response because they had a split second to make this decision.

So some in that split second did make that decision. Everyone else went out to the forest to execute these hundreds - I can't remember how many it was on this first day, if it was hundreds or a thousand. First I'll briefly describe how they did that. They took them out into the forest in groups. They got them onto trucks and drove them out. I may be conflating a few of the events because they're all pretty similar. Prior to this some people had scouted out the forest for locations so they have a location where they line everyone up. I believe on this first one each person was paired up with a victim. So they had the person they were going to shoot next to them and could look them in the face. Then they lined them up in the forest, turned them around, put them on the ground and then they used their bayonet to aim at the last vertebrae connecting to the cranium to get a clean shot because they only wanted to use one bullet. They had a certain amount of ammunition and they had to be conservative with their ammunition.

So they would shoot. But whenever they were slightly off, they would end up exploding the back of the head, of the skull. So they'd shoot and the skull would explode. Bone fragments, brain and blood would just spatter on the shooter and everyone else around them. It was the pure horror of this carnage that resulted in a lot of them needing to go out into the forest and throw up. But no, they had to come back and keep doing it.

So there were 20 or 30 rounds of this, bringing in these groups. Each time they'd move the location a bit further away so that the new batch wouldn't see all the bodies from the old batch, but everyone could hear the gunshots going in. So there were reports from back in the town where everyone heard the gunshot and then everyone that was left in the town was screaming and crying as well as the people waiting to be executed too. Some of them would be screaming and crying. What a lot of the policemen said was that they were amazed that some of them went to their deaths quietly, almost with a dignity.

So there were various reactions; the first few initially, who took the opportunity not to participate and then a group of those that did participate who couldn't handle it anymore. Their excuse often to their superior and their colleagues was "I'm just too weak. I'm just too cowardly." They might not say cowardly but they'd say, "I'm too weak."

He gets into this a bit in the conclusion of the book where he talks about the oddity of this. In the chapter on this where he mentions it, he points out that it was really the ones who refused to go through with this who had courage but everyone involved framed it as cowardice. So they saw themselves as cowards. They weren't strong enough. They didn't have the courage to kill women and children and that's how everyone saw it. Their colleagues and the rest of the police battalion would swear at them and call them, like you said, shit bags or cowards and they'd be the ones to go off and continue with the killing.

As he points out numerous times, it was only 10-20% who didn't engage in these actions or that couldn't. Chose not to or did for a while and then said, "No, I can't do it." But around 80-90% went through 100% the whole time. I believe even a lot of those who originally said they couldn't do it, eventually either had to or did do it because they weren't given the option after that. After that first moment and those first opportunities to say no, it was just taken for granted. "Okay, now you have this operation to do. Go do it!"

The commanders saw the situation and then adapted a bit. So from then on primarily these order police would be given the guard duty. So they would stand guard outside the forest or around the ghetto or anything like that. They weren't necessarily directly involved in the shooting. Of course there were situations where they had to be in future cases because of either a shortage of men or whatever. But it would be the other groups involved, including the auxiliaries taken from prisoner of war camps. This would be the Estonians, the Lithuanians, the Latvians, who after being taken to a prisoner of war camp would vet them for their anti-communist/anti-Semitic feelings and views and then co-opt and conscript them into these other battalions that would act as the killing squads.

So these guys would primarily be the ones who would do the shooting after that. By all reports in the book, they did it with a lot more ease than these order police guys. That's what these guys were doing. They'd kill into the middle of the night or at least until hours after dark, to finish up. Then, like you said, afterwards they would just drink. Even a lot of the commanders involved, not just Major Trapp, but other commanders, would get drunk before the operation. The Lithuanians and Latvians would get drunk beforehand because they knew what was coming.

So add to all this the drunkenness. Just imagine there are all these drunk guys running around shooting people, clearing the villages, It was just mayhem, people screaming, bodies piling up in the streets. Then taking them out to be shot in the forest and then the shooting going on all day out in the forest. So everyone knew it was happening. It had to have been a nightmare.

That was just the shootings at the towns themselves. There were also deportations. They didn't shoot everyone. Sometimes they did shoot entire Jewish populations within a given town or village. Other times they would select who were going to be executed in the woods and the rest would be put onto trains and that's a whole other thing because the order police had the duty of guarding these trains going out to Sobibor and Treblinka.

The way that happened was that they'd have a train with one-to-two thousand Jewish prisoners on it and then 10-15 order police as guards. We've all heard the stories and they're laid out in detail here too. There were 100-200 people crammed into a train car. The doors would then be nailed shut. No food, no water. Again, hot summer days. Traveling for 2-4 days straight, no water, no food. They would get them on the trains and as they trains were going there were air holes in each of the cars that had barbed wire outside of them. The people in the train, usually the strongest ones would manage to get the barbed wire off and knock out some boards and jump out.

So anyone who was seen trying to escape would be shot. Then at a point on one of these journeys they had to change trains and the new engine was this old, rickety engine so they couldn't get up to speed and it was constantly breaking down and stopping. Every time they'd stop, new people would try to escape the trains. They'd be shot. So by the end of that, they'd have run out of ammunition. They'd have killed hundreds of people who were trying to escape and by the time they got there many had died in the trains from being trampled, suffocated and from heat stroke, lack of food. At every stage of this journey it was a complete horror.

I want to read his summary of these trips that were taken on these deportation trains. This is in one of the chapters on the deportations. This is after a document that was sent back, a complaint, again, from one of the people involved on guard duty, probably the officer, laying out all the things that were wrong with this trip, including the bad rations that the Germans got, with no mention of the fact that the more than 8,000 Jews in the cars didn't have any food or water. But he summaries the report as such:

"

This document demonstrates many things - the desperate attempts of the deported Jews to escape the death train, the scanty manpower employed by the Germans, a mere 10 men to guard over 8,000 Jews, the unimaginably terrible conditions, forced marches over many miles, terrible heat, days without food and water and packing of 200 Jews into each train car, etc. That led to fully 25% of the deported Jews dying on the train from suffocation, heat prostration and exhaustion, to say nothing of those killed in the shootings, which was so constant that the guards expended their entire ammunition supply as well as replenishment, the casual mention that even before the deportation, hundreds of Jews judged too old, frail and sick to get on the train were routinely shot in each action.Moreover, the document makes clear that this action was only one among many in which members of Reserve Police Battalion 133 participated alongside the security policy in Galicia during the late summer of 1942."

So that's what these guys were doing for this period of time, clearing out villages, executing hundreds of people a day, sometimes thousands, and then shipping off thousands of people in the trains and killing hundreds on the way, either deliberately or through neglect of the passengers. At the end of the book he's got the tables for Reserve Battalion 101 showing the known minimum estimates for the number of Jews they killed or deported.

There are a bunch of huge massacres, like Józefów.

Corey: Yes.

Harrison: They shot 1,500 people that day, 1,700 the next month in another operation, 1,100 in another and then looking at the others, 960, 200, 200, 100, 150, 290, 300, 1,000. So they were killing up to 1,700 people a day in these shootings and then with the deportations, 5,000, 10,000, 2,000, 7,000. And again, if any number of these deportation train rides were as bad as the one that was just written about, more than 25% of the people on those trains would die en route through suffocation, exhaustion or from trying to escape and being shot.

Corey: Just to put that into the big picture, at the beginning of the book Chris Browning writes about the number of victims of the Final Solution who were still alive in March 1942. About 75-80% of the victims of the Final Solution were still alive but 11 months later in 1943, the numbers were completely reversed and it was largely because of battalions like this and the choices that "ordinary men" were making in the elimination of all of these hundred and hundreds of thousands of people.

I just wanted to go back a little bit. You had discussed the ethical stances that some of these people had chosen in not wanting to participate. I want to read a little bit from the book. This is what he has to say.

"

Most of the interrogated policemen denied that they had any choice. Faced with the testimony of others, many did not contest that Major Trapp (in this particular instance of the massacre at Józefów)

had made the offer of refusing to murder but claimed that they had not heard that part of the speech or could not remember it. A few policemen made the attempt to confront the question of choice but failed to find the words. It was a different time and place, as if they had been on another political planet and the political values and vocabulary of the 1960s were useless in explaining the situation in which they had found themselves in 1942.Quite atypical in describing his state of mind that morning of July 13th, was a policeman who admitted to killing as many as 20 Jews before quitting. 'I thought that I could master the situation and that without me the Jews were not going to escape their fate anyway. Truthfully, I must say that at the time we didn't think about it at all. Only years later did any of us become truly conscious of what had happened then. Only later did it first occur to me that what I had done had not been right.'"

And another.

"

The two men who explained their refusal to take part in the greatest detail both emphasized the fact that they were freer to act as they did because they had no careerist ambitions. One policeman accepted the possible disadvantages of his course of action 'because I was not a career policeman and also did not want to become one, but rather an independent skilled craftsman and I had my business back home. Thus it was of no consequence that my police career would not prosper."And the last.

"

This Lieutenant Buchman had cited an ethical stance for his refusal. As a reserve officer and Hamburg businessman, he could not shoot defenceless women and children. But he too stressed the importance of economic independence when explaining why his situation was not analogous to that of his fellow officers. 'I was somewhat older than, and moreover a reserve officer, so it was not particularly important to me to be promoted or to otherwise to advance because I had my prosperous business back home. The company chiefs on the other hand, were young men and career policemen who wanted to become something."Here's the final quote.

"

In short, the psychological alleviation necessary to integrate Reserve Police Battalion 101 into the killing process was to be achieved through a twofold division of labour. The bulk of the killing was to be removed to the extermination camp and the worse of the on-the-spot 'dirty work' was to be assigned to the individuals talked about earlier (these ruthless murderers).

This change would prove sufficient to allow the men of Reserve Police Battalion 101 to become accustomed to their participation in the Final Solution. When the time came to kill again, the policemen did not 'go crazy'. Instead, they became increasingly efficient and calloused executioners."

Harrison: One more from that same chapter, on these reactions. He talks about one guy, pointing out that he was the remarkable one. I'll read the whole paragraph.

"

In addition to the easy rationalization that not taking part in the shooting was not going to alter the fate of the Jews in any case, the policemen developed other justifications for their behaviour. Perhaps the most astonishing rationalization of all was that of a 35-year-old metalworker from Bremmerhaven. 'I made the effort and it was possible for me to shoot only children. It so happened that the mothers led the children by the hand. My neighbour then shot the mother and I shot that child that belonged to her because I reasoned with myself that after all, without its mother, the child could not live any longer. It was supposed to be, so to speak, soothing to my conscience, to release children unable to live without their mothers.'"Then Browning comments:

"

The full weight of this statement and the significance of the word choice of the former policeman cannot be fully appreciated unless one knows that the German word for release, erlösen, also means to redeem or save when used in a religious sense. The one who releases is the erlöser, the saviour or redeemer."

So this guy saw himself as the saviour of these children for killing them after their mothers have been murdered by the guy next to him. But he also points out that after this killing, he writes,

"

The resentment and bitterness in the battalion over what they had been asked to do in Józefów was shared by virtually everyone, even those who had shot the entire day."

Maybe this will lead into the second part of our conversation here,. The point he's making is that these were ordinary people. These weren't a bunch of psychopaths that they got together to form this police battalion. It would be as if you were to go around to various businesses around your neighborhood and randomly pick 500 guys. These would be the men in this battalion. Almost universally, they reacted with revulsion. I wouldn't say they couldn't live with themselves, but at the very least they had negative emotional reactions to what they'd done that day, even if they hadn't refused to do anything about it. They had a moral revulsion even if they couldn't frame it in terms of moral revulsion, just the physical.

So in the last chapter of the book he gets into the explanations, the whys. He tries to dig a bit deeper into the explanation for how this happens. Whenever this kind of discussion comes up there are a few pat responses and theories that will come up. Some of them might be 1) that all these Nazis were brainwashed and it was the Nazi government that brainwashed them into hardened serial killers, essentially; then 2) it was just conformity; or 3) they were all just psychopaths; or 4) if you take in the reason that Jordan Peterson often brings up this story, it's the reaction of someone viewing that from the outside, "Oh well that would never be me. I'd be the person who would refuse". Well Browning wouldn't agree with that and we'll read how he gets into that later on.

But I want to go through some of the explanations he gives and then how they either do or do not apply to this reserve battalion and what he could find out about these individuals themselves. The first point he makes is that, again, one of the pat, stock answers given to something of this sort is that it's the brutalization of war. When you're engaged in a war there's a dehumanization and a brutalization that takes place. This of course is true, so he concedes this point that this is a factor, especially a race war. Total war, one country against another is bad enough. When you add a racial element to that with elements of race superiority and the total dehumanization of the enemy, that polarizes things even further.

So it's no surprise that you get atrocities in war. He brings up a few examples from all kinds of wars including Vietnam and various other ones, but makes the point that most of the atrocities that take place in wars ordinarily, are from a breakdown in etiquette, from a breakdown in the rules of war. Oftentimes there are at least stated or implicit rules of war that then get broken. The chain of command gets broken and you get atrocities that aren't directly ordered by the top chain of command.

It's not like in all these wars you get explicit orders, "Okay, go and commit a massacre in this village". Sometimes you do, but oftentimes you don't. So a lot of the massacres that do take place are a breakdown of the chain of command and that is through this brutalization process that he's talking about. But he points out that this doesn't apply to the reserve battalion because these guys weren't war-hardened. They hadn't been developed in combat. They hadn't experienced anything of the sort.

The way he puts it is it wasn't the war that led to the brutalization, it was the brutalization of the murders that actually led to the - I can't remember. He had a really well formulated way of putting it, that it was the act of taking part in the atrocity that led to the numbing of their feelings and the brutalization of their feelings. It wasn't the other way around through the escalation of the war and of the killing to then reach that point. They were put into the middle of it. They didn't have the chance to become numbed to seeing their buddies killed in war or anything like that. It was just being thrown into the middle of a village out of nowhere and then being told to shoot a whole bunch of people. So that didn't really apply in this case.

The next one was the negative racial stereotyping and other methods of distancing. That includes bureaucracy. So that too was a factor of course in the war and in most of these wars and it is proven again and again that this distancing phenomenon takes place. It's easier to dehumanize and to kill essentially when there's distance between you and your victim. We see this nowadays with the drone wars. It's a lot easier to kill someone with a joystick than it is to stab them right in front of them, one-on-one, to personalize it. It's a lot easier to kill people from a desk than it is with your own two hands.

The other one is the idea of a selection process, that the SS for instance, or the people involved in these massacres were selected because of their psychological features that would make them adaptable to this situation. Then the idea of self-selection too. It was the violent people who would join the SS for instance. They would select themselves to enter this organization because they knew it could be an outlet for their violent tendencies. But as he points out, that doesn't apply to Battalion 101 either because they weren't selected and they weren't self-selected. They were selected because they were the only people available. There was nothing about them personally, about their careers or about their histories that would point to them being good executioners. They were just random people off the street, essentially.

Corey: Yeah, and if anything, they were negatively selected because at this point in time, enlisting in the police was one way of escaping war service.

Harrison: Yeah, escaping.

Corey: Escaping the need to actually go on the front lines and do these things. So if anything, you're selecting for people who are a little bit more pacifist or who go along to get along, maybe. They don't want to go out and murder. They just want to do whatever they can in order to maintain the lifestyle that they're living.

Harrison: I want to read a sentence or two from the section where he's talking about bureaucratic life.

"S

egmented, routinized and de-personalized, the job of the bureaucrat or specialist, whether it involved confiscating property, scheduling trains, drafting legislation, sending telegrams or compiling lists, could be performed without confronting the reality of mass murder."

So again, this is like Hannah Arendt's banality of evil, the bureaucrat stamping people to their deaths, that kind of things. As we'll see, that's actually supported by some research, the studies everyone's heard about but we'll get into them because they do have some good insights.

But on the subject of this selection and self-selection, I want to read this paragraph.

"

Subsequent advocates of a psychological explanation have modified the Adorno approach (Adorno was the guy that came up with the F-scale, the Fascist personality, the right-wing authoritarian inventory)

have modified his approach by more explicitly merging psychological and situational social, cultural and institutional factors. Studying a group of men who had volunteered for the SS, John Steiner concluded that, 'A self-selection process for brutality appears to exist'. He proposed the notion of the sleeper, certain personality characteristics of violent-prone individuals that usually remain latent but can be activated under certain conditions."

He gives the example of these guys that in normal life, pre-war, seemed to be ordinary people. In war, this violent barbarian comes out of them and then after war they go back to regular life. Then he quotes some people who don't agree with that. For example a guy called Staub, "

Evil that arises out of ordinary thinking and is committed by ordinary people is the norm, not the exception." So he's saying that no, there aren't these pre-existing personality constructs. It's all normal people.

So you have these two extremes, right? So far we've got the first guy Adorno saying it's all personality, Steiner saying it's personality and then the environment that brings out that personality in extreme situations, and then you've got the other extreme which is, it's all just normal people so it all must be situational. Then one more bit.

"

If Staub makes Steiner's sleeper unexceptional, Sigmund Baumann goes so far as to dismiss it as a metaphysical prop. For Baumann, 'Cruelty is social in its origin, much more than it is characterological. Baumann argues that most people slip into the roles society provide them and he's very critical of any implication that faulty personalities are the cause of human cruelty. For him the exception, the real sleeper, is the rare individual who has the capacity to resist authority and assert moral autonomy but who is seldom aware of his hidden strength until put to the test.'"

I just want to make a few comments on these approaches so far, first to say that they're all idiots but they're all kind of smart at the same time. They've all got something going for them. The first thing that stuck out to me was Steiner's idea of the sleeper. That sounds like a good idea to me. It's like each person has this one piece of the puzzle and then looks at it to the exclusion of all contradictory evidence when what you should really do is realize that humanity is complex and there is a variety of different personality types. It's going to be different in different situations and with different individuals. I believe, yes there are sleepers.

If you read

Political Ponerology, which we've discussed on the show numerous times, Lobaczewski gets into this kind of stuff in-depth and has aspects of all of these different approaches because they're all true in certain situations to certain degrees. So there are individuals who have certain personality characteristics that either lay latent for a while or don't really express themselves but when given the opportunity, it's like, "Yes, now I have the opportunity to do this. I've always wanted to do this. Now I get the chance." And then in regular life, back to normal.

It's also possible, if you just look at the phenomenon of serial killers, like the show we did on Israel Keyes, that perhaps these people aren't perfect in their ordinary life before and after, it's just that in a war environment, it's the chance to take the mask off temporarily because now their own inclinations and behaviour are social, morally acceptable. It's okay now if I just kill a bunch of people right out in the open because no one's going to sanction me for it. There are people like that.

So the impression you get is that there is something to this personality-centered approach, that there are a small minority of people, we call them psychopaths, who do have these tendencies, who have no problem killing and oftentimes enjoy it because there are extreme sadists among the psychopathic demography, that when put into a war situation, it is time for the mask to come off. It's an acceptable way for them to reveal who they really are. But that's only going to be a tiny minority of the population. Everyone else is going to have a different psychology because they themselves have a different psychology. They have a different personality makeup.

So for this guy that says that evil arises out of ordinary thinking and is committed by ordinary people and that that's the norm, well it's only the norm in the sense that normal people are the norm. Yeah, for sure. Most people have a relatively normal personality structure. They have normal emotions. A small minority has very F-ed up emotions, no emotions. They have this negative emotional substructure where they can't feel. They don't feel empathy. They don't feel anything and in fact they often feel the opposite. They like being cruel. They get something out of it, just like serial killers. Again, serial killers are an extreme example, but you can learn something from them because they have these tendencies in the most extreme form possible. But only a fraction of psychopaths are serial killers but all psychopaths have something in common, and that is that total lack of conscience. So there's this guy who says that he's critical of any implication that faulty personalities are the cause of human cruelty. Well Jesus! Just read one account of a serial killer and you'll get an idea of what a faulty personality can do!

He then goes on to talk about some of the studies. Of course there's Zimbardo's Stanford prison experiment that he talks about. For those not familiar with it, he's the guy who set up the experiment where they got a bunch of ordinary people - at least this is the way it's sold - a bunch of ordinary people, randomly assigned them as guards or prisoners and then just let them lose and some of the guards became total sadists and some of them weren't. That's it in a nutshell.

Corey: Right. What was the one flaw in the study that came out years later? Was it that Zimbardo was coaching the guards to be more intense and more aggressive, which doesn't necessarily change the information. It's just good to have that information in mind. It doesn't make the study irrelevant. It's still useful. I think that was the main detail that you'd want to keep in mind when making comparisons.

Harrison: Yeah. So there's some evidence that he gave some coaching that wasn't shown in the published paper and also there might have been an element of self-selection in the way that they found volunteers. So it's not a totally clean experiment but it does show some interesting things. He points out that about one-third of the guards emerged as cruel and tough, constantly inventing new forms of harassment and enjoying their new-found power. The middle group was tough but fair. They played by the rules and did not go out of their way to mistreat prisoners, but only two, less than 20% emerged as good guards who did not punish prisoners and even did small favours for them.

Browning sums up,

"

Zimbardo's spectrum of guard behaviour bears an uncanny resemblance to the grouping that emerged within Reserve Police Battalion 101. A nucleus of increasingly enthusiastic killers who volunteered for the firing squads and Jew hunts, a larger group of policemen who performed as shooters and ghetto clearers when assigned but did not seek opportunities to kill and in some cases refrained from killing, contrary to standing orders when no one was monitoring their actions, and a small group, less than 20% of refusers and evaders."

This is why, while I appreciate Jordan Peterson's take on it, this is why I don't totally agree with the way he presents it because his presentation is geared to an individual for a pedagogic purpose, to teach them something, that "you could be this person". But in reality, you take 100 people, put them in this situation, not all 100 are going to behave in the same way. It's not like every one of them is going to be an executioner. You do get a small minority that does refuse and there is always that small minority. Of course the fact is that the vast majority do not refuse so chances are you're going to be one of the killers. But if we want to look at human nature in its variety, you have to acknowledge that there are some people who don't who for whatever reason will not engage in that. For whatever reason they give, they might give a self-serving reason, but the fact is they're not out in the forest shooting people.

Then moving on to the next one, one excuse that was often given by these people in interrogations was that they simply had no choice. He points out that no, it wasn't true. They were actually given a choice. Or some people say that people in this situation, when they commit atrocities, it's just because they were given orders. That's not true, especially in this case with Major Trapp. They

did have the choice, explicitly and they understood. There are reports of his inferiors of him walking around crying after the first one saying, "Oh god! Why did they give me these orders?! I can't believe this!" He could not take it.

In this case they knew they had the opportunity not to. Then there was the fact that they were under what's called putative duress. So they had to do it. They were in this situation and it was just the pressure of their superiors giving them orders and then the fact that if they didn't bad things would happen to them. But he points out that there's not one case where a refuser was given any serious punishment and not only in this battalion. He gives the implication that almost in the entire literature on this subject, whenever there's an atrocity like this, it's usually and most often and almost always the case, that nothing happens to the people who don't do anything. They may get called names. But at least in Battalion 101 in particular, no one experienced any bad consequences if they didn't. The one guy who was most adamant that he not participate actually demanded to be transferred back to Hamburg and eventually got that.

So there were no bad consequences for not participating, despite the threats. Those are a couple of points that he makes on that. And then the last one which to me is most interesting, is the Milgram experiment. It's kind of cliché at this point. Most people know about it. It's talked about all the time. We'll give a little summary for those who haven't heard about it, but there's so much in there and it's probably one of my favourite experiments of this type because the more you look at it and the variations, there's so much that you can learn from this one experiment, despite its flaws and the things that it didn't and can't test for.

The Milgram experiment was the famous one where subjects were put in a room with a button in front of them and told to give shocks to the other person in the other room who was taking a certain test, a vocabulary or spelling and every time they got an error they were to give them an electric shock. As they made more errors they were to increase the voltage. As Browning sums up, the vast majority of people ended up giving shocks that would have killed the person. So they can either see or hear the other person screaming, begging no and then the person in charge of the experiment says, "No, you have to give that shock". Some of these people were sweating and saying, "Oh god!" They'd give the shock.

And of course the person isn't actually getting a shock. They're a confederate. They're in on the experiment, but the person giving the shocks doesn't know that. That's the experiment in a nutshell. But there are also variations on it to show what factors might either increase their conformity or decrease it. I want to read some of the different situations here.

"

Several variations on the experiment produced significantly different results. If the actor/victim was shielded so that the subject could no longer hear or see their response, obedience was much greater. If the subject had both visual and voice feedback, compliance to the extreme fell by 40%. If the subject had to touch the actor victim, physically, by forcing his hand onto the electric plate to deliver the shocks, obedience dropped to 30%. If a non-authority figures gave orders, obedience was nil. If the naïve subject performed a subsidiary or accessory task but did not personally inflict the electric shocks, obedience was near total.In contrast, if the subject was part of an actor peer group that staged a carefully planned refusal to continue following the directions of the authority figure, the vast majority of subjects, 90%, joined their peer group and desisted as well. If the subject was given complete discretion at the level of electrical shock to administer, all but a few sadists consistently delivered a minimal shock. When not under the direct surveillance of the scientist, many of the subjects cheated by giving lower shocks than prescribed, even though they were unable to confront authority and abandon the experiment."

So again you see that it's not that simple. It's not like there's one or two responses and you fall into either of them. In the ordinary situation, most people end up giving all these shocks. You have some that drop off right away and say no and then a few more that drop off as things get worse, but overall the majority of them go through with it, just like Reserve Battalion 101. Then again you get this distancing factor. So the closer you are, the less likely you are to do it.

So if you have to actually force the person's hand onto the shock, only 30% will do it, or something like that. If you can't hear them or see them, fine, most people will do it. Again, it's the drone joystick phenomenon. If the person giving the order isn't a researcher, just some schlub off the street...

Corey: Not wearing a lab coat.

Harrison: Not wearing a lab coat, they won't listen to him. On the other hand, if it's just some schlub off the street that they've gotten and put into a lab coat, they'll listen to him because he has the

appearance of authority.

So those are some of the variations. Browning then applies these to the battalion with a few other examples. He give some other factors that could contribute to disobedience or refusal or their opposites. For example, one is the momentum of the process. So the more you do it, the more you're invested in finishing it. So if you're halfway through the experiment so far, there's momentum. You're already doing it so you're more likely to keep doing it. A variation on that is the situational obligation or etiquette. So now you'd be rude if you refused to carry on. And you don't want to insult this esteemed researcher/doctor who might just be some schlub off the street wearing a lab coat. There's a social anxiety over the potential punishment for disobedience. "What if I do refuse now? What if I say no? What's going to happen to me? Well something bad might happen to me." So all these things are going on in the head as this goes on.

This is what I thought was the best thing, where he's talking about the mix between authority and conformity because it wasn't all authority. For example, Trapp obviously didn't want to be doing this. He wasn't enforcing it. He wasn't saying everyone had to do it. He was explicitly giving the option not to. But there was authority in the sense that these orders had come from the top. So in this case Trapp was in the trenches with them. He didn't want to do it. They didn't want to do it but they had this distant, central authority telling them they had to do it.

So that's where the authority was in this situation. But perhaps the biggest was the peer pressure, the actual impulse to conform. I'll get to that in a second. There are a couple of other points he makes that you can see from the Milgram experiment. There's of course the direct proximity. We see that in the Reserve Battalion. When they were paired up one-on-one with their victims it was a lot harder for these guys to do it. When it was more distant, when it was just a mass of people they were shooting at, it was a lot easier for them to carry out these executions.

And then there's the surveillance. When you're being watched by some superior, you're more likely to go along with it. When there's no one really watching you can pretend to do it. You can miss. You can shoot off next to their head as opposed to the back of their skull. Or you can go off into the woods and just get lost for a while and say, "Oh, I was off doing something else."

Also in a lot of these cases it wasn't very organized. They had different battalions and groups that would mix up so there weren't a set number of people in each execution squad, essentially. So if you were missing, no one really knew because no one really knew where you were supposed to be. So that's how a lot of these guys got away with avoiding these. Do you want to go?

Corey: Yeah. I just wanted to comment on that whole idea of this out-of-sight/out-of-mind that you see in the Milgram experiment where if you can't see the person you're electrocuting and you can't hear them then you just assume they're not dead. And also, if you're just walking off in the woods and you're not actually seeing people getting murdered or whatever, as long as you are comfortable and you're not nauseous, it's as if the final solution isn't necessarily happening.

I think this describes a large number of people. In the Milgram experiment, how many people was it who were able to administer shocks all the way up to death?

Harrison: Under what conditions?

Corey: Under the condition that they could not see or hear the victim.

Harrison: Oh, I think that was the one where it was almost everyone.

Corey: Almost everyone was able to do that. Let that sink in.

Harrison: It was when they were performing a subsidiary task that it was near total. So if someone else was giving the shock and they were just the one massaging their elbow while they were pushing it - that wasn't really what they were doing. If they were given a bureaucratic role, for instance, then it was near total. So there was no one that wouldn't go along with it if it was someone else giving the shock.

Corey: It's something that this book delivers deep down as you read it, what people are capable of, just purely, the kind of potential for evil that lurks out there. As you discussed, there's definitely psychological factors involved but that's not the whole story.

Harrison: No. It reminds me of another passage in

Ponerology where he's talking about the prison guards and how when Lobaczewski was arrested and tortured he made the point to one of his torturers as a sarcastic remark, "Well why do you guys always end up in the mental asylum with your brains degenerating after all this work?" The guy looks at him and says, "Well it's such damn horrible work!" So Lobaczewski, as a psychologist, knew that that was an occupational hazard for these guys who were working in the prisons. It was such horrible work that it did a number on their bodies, on their brains. Being put in the role of a prison guard for so long degenerated their brains.

That's the complexity and variety that you see. We may not all be born killers but the vast majority of us can be influenced to be killers but we'll still have our normal emotional reactions. We won't

like what we're doing, but we'll still do it. We might suffer some consequences but we'll still do it. That's the take home message that people should take from these things, not that these other people are evil. "Look how these other people are evil. Look what evil things they do." No, that's you! You would do that in a similar situation or at least it's likely that you would, it's probable that you would. Chances are, just based on statistics, you wouldn't be one of the guys that refused. That's the message to take from that.

Then one last point on the conformity and then we'll wrap up for today. He's trying to give some of what must have been going on in these guys' minds. I'll read a bit.

"

Along with ideological indoctrination, a vital factor touched upon but not fully explored in Milgram's experiments, was conformity to the group. The Battalion had orders to kill Jews but each individual did not. Yet 80-90% of the men proceeded to kill though almost all of them, at least initially, were horrified and disgusted by what they were doing. To break ranks and step out, to adopt overtly non-conformist behaviour was simply beyond most of the men. It was easier for them to shoot. Why?First of all, by breaking ranks, non-shooters were leaving the dirty work to their comrades. Since the battalion had to shoot even if individuals did not, refusing to shoot constituted refusing one's share of an unpleasant collective obligation. It was, in effect, an asocial act, vis-à-vis, one's comrades. Those who did not shoot risked isolation, rejection and ostracism."

So put yourself in the situation. It's uncomfortable, but think about it. You've got a bunch of friends, people you're close with, people that you've been in the trenches, figuratively, with have got a really horrible task to do and you don't join them. Of course you shouldn't join them. No one should join them, but the emotional reaction you'll have is, "They're doing the dirty work and I'm just selfishly evading my obligations and I'm leaving the dirty work to them."

Corey: Right. That's the really critical part. That's how it's viewed as dirty work. It's a dirty job. It's like on Discovery Channel or whatever that network television show is, "Dirty Jobs". It's guys who have to go around and repair things under the ocean or work in horrible places. To the people in this era, that's all this was. Racial ideologies pretty much ruled the day, social Darwinism, eugenics, the progressive era in Nazi racial ideas. All of these racial ways of viewing things had the strength of science and the power and brilliance of Darwinian evolution behind it, this massive idea that just seemed so obvious. It was all over journals by academics and intellectuals. Everyone was talking about and singing the praises of these different racial categories and all this.

One thing that he points out is that this made it possible for ordinary Germans to view this just as dirty work. "Well they're not like us. They're not us." This was just a part and parcel of the intellectual era.

Harrison: There's a section in here where he gets into the ideological material, the pamphlets and stuff that they'd have to read, the meetings they'd have to go to and their hourly indoctrination for the week. We haven't really gotten into that, but read the book for insight into what was going on there.

I want to read on from that last quote that I read on the isolation, rejection and ostracism that could result from shirking your responsibility.

"

This threat of isolation was intensified by the fact that stepping out could also have been seen as a form of moral reproach of one's comrades. The non-shooter was potentially indicating that he was 'too good' to do such things. Most, but not all non-shooters, intuitively tried to defuse the criticism of their comrades that was inherent in their actions. They pleaded not that they were too good, but rather that they were too weak to kill. Such a stance presented no challenge to the esteem of one's comrades. On the contrary, it legitimized and upheld toughness as a superior quality. For the anxious individual, it had the added advantage of posing no moral challenge to the murderous policies of the regime though it did pose another problem since the difference between being weak and being a coward was not great."

So that's what you see in practically all of the people who didn't do this. It wasn't for any noble high purpose. I was because they were too weak, like we said earlier. It was because they just didn't have the stomach for it. So he writes,

"

Insidiously therefore, most of those who did not shoot only reaffirmed the macho values of the majority according to which it was a positive quality to be tough enough to kill unarmed, non-combatant men, women and children and tried not to rupture the bonds of comradeship that constituted their social world."

Did you have any final thoughts before I give my final thought?

Corey: No.

Harrison: Okay, well to close out today I want to read the final paragraph because I think Browning says it best.

"

The reserve policemen faced choices and most of them committed terrible deeds. But those who killed cannot be absolved by the notion that anyone in the same situation would have done as they did for even among them, some refused to kill and others stopped killing. Human responsibility is ultimately an individual matter. At the same time however, the collective behaviour of Reserve Police Battalion 101 has deeply disturbing implications. There are many societies afflicted by traditions of racism and caught in the siege mentality of war or threat of war. Everywhere a society conditions people to respect and defer to authority and indeed could scarcely function otherwise. Everywhere people seek career advancement. In every modern society, the complexity of life and the resulting bureaucratization and specialization attenuate the sense of personal responsibility of those implementing official policy. Within virtually every social collective, the peer group exerts tremendous pressures on behaviour and sets moral norms. If the men of Reserve Police Battalion 101 could become killers in such circumstances, what group of men cannot?"

So with that, we want to thank you for listening today and we'll be back next week. So make sure to like if you like this video and subscribe if you haven't already so you can watch our future shows and get notifications on YouTube. Thanks everyone and take care.

Corey: Bye everybody.

The below linked article discusses the emasculation of men about one generation after mine. (In Canada but it could just as easily be in most places in the US today.)

I have dealt with folks with guns, and I have protected women unknown to me. I bet most SOTTguys have done so - at least the latter. But today's truthseeker has a great article - Young Men Cowered While Young Women Were Massacred - about what 'feminism' long ago wrought: [Link]

Being down in the USA I do not recall this event. My reaction? PATHETIC!!! Try that at my high school and all the white and black guys would put aside our literally deadly feuds to rip that fucker limb from limb!

Talk about going out with a bang - at least one of his eyeballs would have been in ripped apart by my teeth as I died.

R.C.

P.s., The comments there are likewise on point.

RC