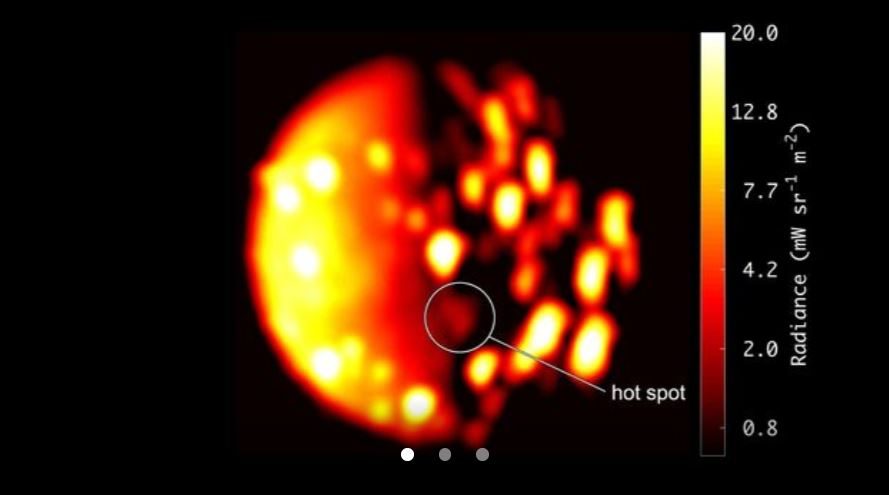

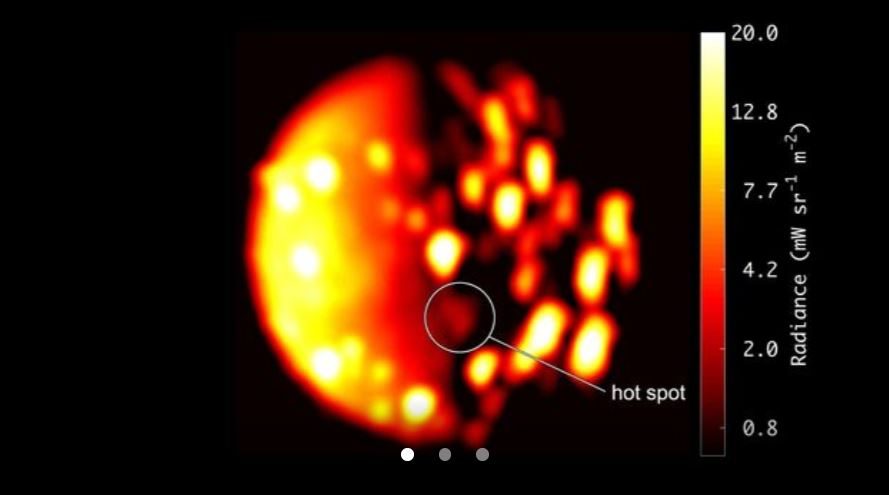

© NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/ASI/INAF/JIRAMThis annotated image highlights the location of the new heat source close to the south pole of Io. The image was generated from data collected on Dec. 16, 2017, by the Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) instrument aboard NASA's Juno mission when the spacecraft was about 290,000 miles (470,000 kilometers) from the Jovian moon. The scale to the right of image depicts of the range of temperatures displayed in the infrared image.

Higher recorded temperatures are characterized in brighter colors - lower temperatures in darker colors.

NASA's Juno spacecraft recently

spotted a possible new volcano at the south pole of Jupiter's most lava-licious moon, Io. But this volcanically active moon is not alone in the solar system, where sizzling-hot rocks explode and ooze onto the surface of several worlds. So how do Earthly volcanoes differ from those erupting across the rest of the solar system?

Let's start with Io. The moon is famous for its hundreds of volcanoes, including fountains that sometimes spurt lava dozens of miles above the surface,

according to NASA. This Jupiter moon is constantly re-forming its surface through volcanic eruptions, even to this day. Io's volcanism results from strong gravitational encounters between Jupiter and two of its large moons, Europa and Ganymede, which shake up Io's insides.

Rosaly Lopes, a senior research scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, managed observations of Io between 1996 and 2001, during the

Galileo spacecraft mission to Jupiter.

"Io has lots of caldera-like features, but they are on the surface," Lopes told Live Science. "There are lots of lava flows and lots of lakes. Lava lakes are pretty rare on Earth. We have half a dozen of them. We think they have occurred in the past on Venus and Mars. But on Io, we actually see lava lakes at the present time."

Hawaii's Kilauea volcano is one such spot on Earth dotted with lava lakes.

Juno scientists asked for Lopes' help in identifying Io's newly found hotspot. She said the new observations of Io are welcome, because Galileo was in an equatorial orbit and could rarely see the poles; by contrast, Juno is in a polar orbit and has a much better view. There are some hints that Io might have larger and less-frequent eruptions at the poles, she said, but scientists need more observations to be sure.

Comment: See also: