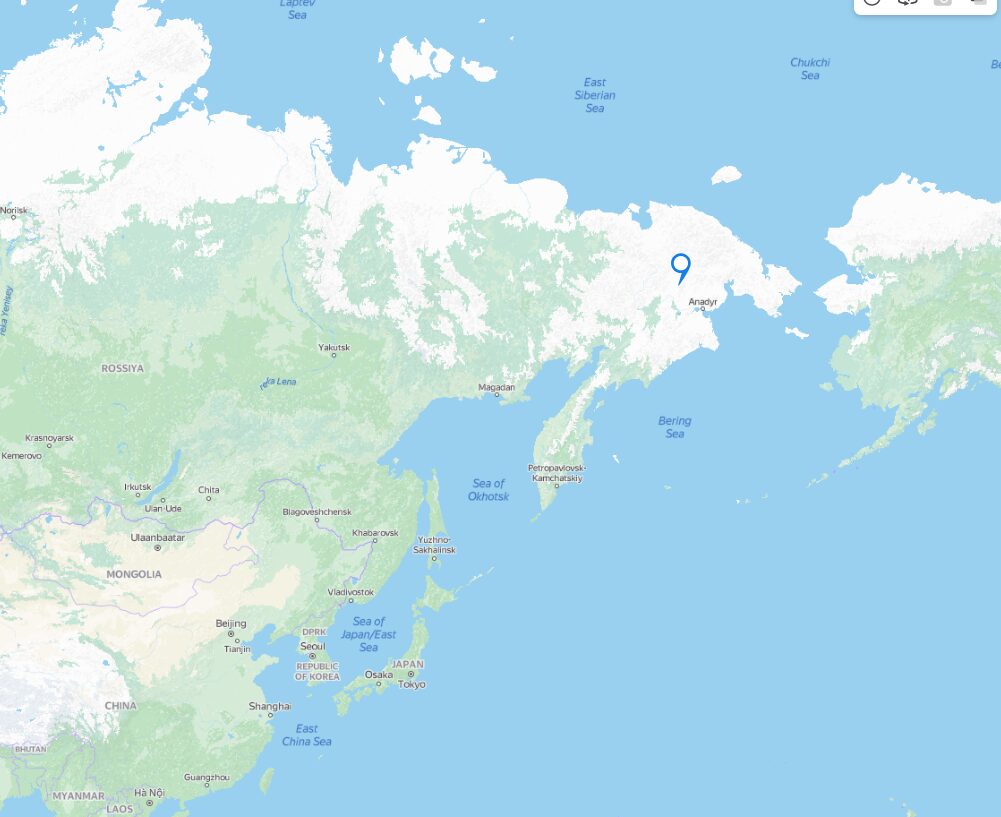

The spectacular art gallery - scientists found 350 stone planes, each with dozens of drawings - was 'opened' at least two thousand years ago, when ancient artists embossed petroglyphs on rocks of what is now Chukotka, Russia's easternmost corner.

The area is so remote it can only be reached by a helicopter. The nearest town to the site is Pevek, some 5,555 km east of Moscow.

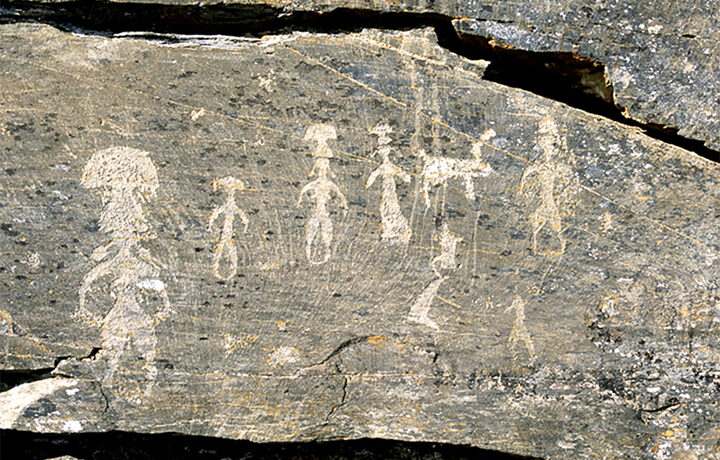

The most striking part of the gallery are petroglyphs of 'mushroom people' - women and men with large mushroom on their heads, or with one or several mushrooms replacing heads. In some cases their legs are shaped as mushroom stems, too.

Russian experts have christened them the 'fly agaric people' after the hallucinogenic mushrooms it is believed they consumed.

'They were often depicted with their arms spread apart, and legs slightly bent at the knees,' said Dr Mikhail Bronstein, chief researcher at the the Russian State Museum of Oriental Art.

The Pegtymel petroglyphs highlight 'a ritual, magical dance, comparable to the dances of shamans', according to a leading hypothesis, he said.

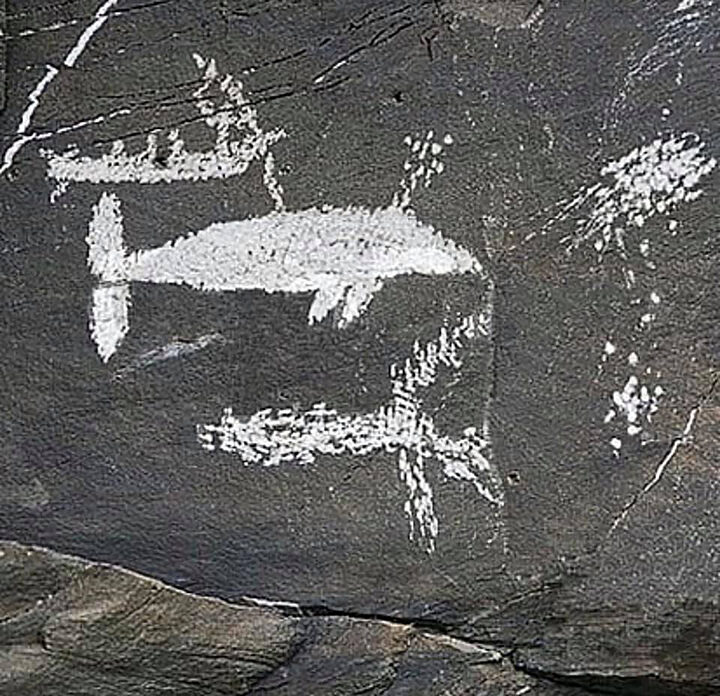

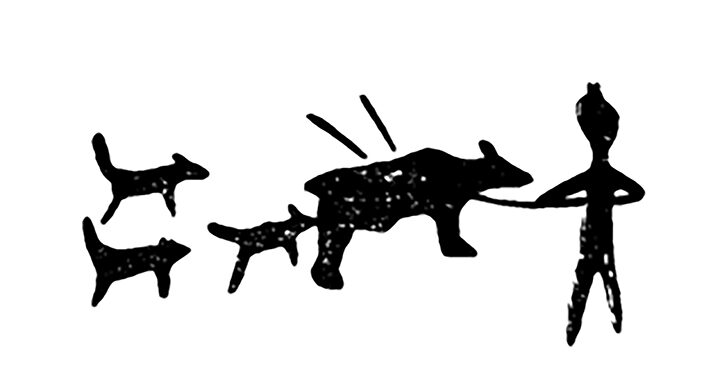

They were clearly skilled hunters, knowing how to use dogs to get brown bears, hunting whales and reindeer - some petroglyphs show them using boats to spear reindeer as they swam across rivers on seasonal migrations.

Despite the remoteness, they must have been in touch with people far to the south with metal smelting abilities, because some of the petroglyphs were made with metal cutters.

The artists used pieces of white quartz for sketches; fine white lines are still visible on the rocks.

'Among the people who inhabited Chukotka in ancient times, there were pioneers ready to take risks and go to foreign, unknown lands,' wrote Dr Bronstein.

'The Pegtymel petroglyphs give us a rare opportunity to look into the mysterious world of mythological representations of ancient people, destroying the myth that still exists today about the cultural backwardness of Chukotka, allegedly from ancient times,' wrote Dr Bronstein.

'It was not at all like that. This remote Arctic outpost was a land of polar hunters, nomads, sailors and talented artists 2,000 years ago, with evident contacts to the outside world', he said.

This summer the first scientific expedition since 2008 got to the site to start a major project on preserving unique stone drawings as they get destroyed with time.

Five archeologists and three volunteers spent two weeks gathering photo material to create 3D models of Pegtymel petroglyphs, and to map the whole 'gallery'.

The aim is to have exact copies of the Arctic petroglyphs on online display.

'It's impossible to complete the project within a year. We found stone planes, and obtained their exact coordinates; hopefully we'll be able to publish first results by the end of this year', said leading scientist of the expedition Yelena Levanova, head of PaleoArt Centre at Russian Institute of Archeology.

They aim to return to Pegtymel next summer to continue copying the petroglyphs until the whole gallery is preserved in 3D.

It takes one to know one LOL!!