A five-year research project by a team of archaeologists led by Professor Stephen Rippon at the University of Exeter shows the links between merchants in Exeter and France, the Low Countries, Spain, Italy, Portugal, and the Mediterranean.

The artifacts are held by the Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Art Gallery in Exeter. The analysis has helped experts establish where various pottery vessels found in Exeter were made,

The analysis shows that in the Late Roman period people in Exeter traded with other ports along Europe's Atlantic coast and in the Mediterranean. Fine quality table wares were imported from South West France, while vessels carrying olive oil, wine, and fish sauce arrived from North Africa.

The research shows pottery was imported from mainland Europe in the medieval period from Normandy, Brittany, and France's South West coast, though some vessels also came from the Low Countries. In the 15th century pottery vessels were imported from even further afield including northern France, Spain, Portugal, and Italy.

The research project "Exeter: A Place in Time," is a partnership between the University of Exeter, Cotswold Archaeology, Historic England, Exeter City Council, the Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Art Gallery, and the University of Reading. It was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, Historic England and the University of Exeter.

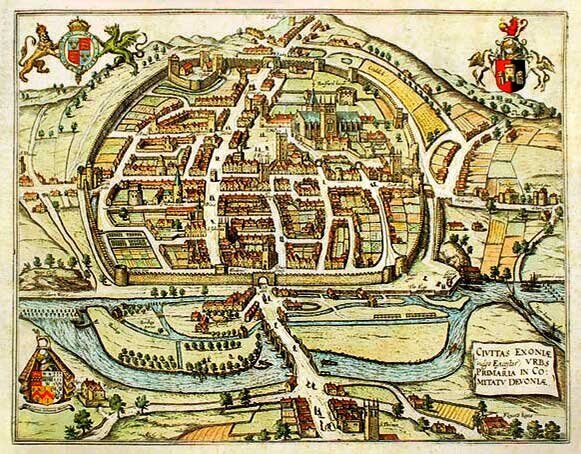

Exeter began life as a fortress housing a Roman legion that, for a few years in the 60s AD became one of the most important supply bases in Britain as the Roman army tried to defeat a rebellion led by the British queen Boudica.

Exeter was a major town in both the Roman and medieval periods, with its fluctuating fortunes reflecting demand for local resources such as tin and silver, and its role in international trade.

When Britain ceased to be part of the Roman Empire in the early 5th century AD Exeter was abandoned for a few hundred years, but from the 10th century its fortunes revived. It became the fifth most productive mint in England, and a major center for the tin trade. In the 16th and 17th centuries the region's production of woollen cloth led to Exeter becoming the sixth wealthiest city in England.

Most of the pottery used by people living in Exeter was produced locally, although chemical analysis carried out as part of the project shows that vessels known as "Fortress Wares" were made from fine-quality potting clays found in the Teign Valley east of Dartmoor. This suggest that the Roman potters scouted quite widely around Exeter's hinterland, searching for good quality material to work with.

Scientific analysis of another distinctive type of pottery found across the South West — South Western Black Burnished Ware — shows it was produced in the western parts of the Blackdown Hills, perhaps in the Hemyock area. In the Roman period clay from there was used to produce roofing tiles, and stone was quarried to make quern stones for grinding corn. Iron was also produced, showing how this now rural area was once a hive of industry.

Chemical analysis of animal bones from Exeter carried out as part of the project shows animals were moved seasonally during the Roman period, around a thousand years before the practice of taking livestock to graze on Dartmoor in the summer was recorded in written documents in the medieval period.

Professor Stephen Rippon of the University of Exeter said: "It is great to see this major study of Exeter's emergence as a major city published. The application of modern scientific techniques has shown us how Exeter was at the center of a network of trade routes that stretched across much of Europe."

Neil Holbrook, Chief Executive of Cotswold Archaeology said: "As an archaeologist who worked in Exeter in the 1980s I was delighted to be a partner on this project. Together we have been able to achieve much more than any one of us could have done alone. The heroic efforts of Exeter City Council archaeologists working to salvage information ahead of redevelopment in the 1970s and 80s were not in vain — we can now see Exeter more clearly in its national and international context, in both the Roman and medieval periods. This project is an exemplar that can be followed by archaeologists and historians interested in other British historic towns and cities."

Owen Cambridge, Principal Project Manager (Heritage) at Exeter City Council, said: "This is an important book which represents the culmination of five years of collaborative research. It results in a comprehensive re-evaluation of our understanding of how the City evolved, the influences and events which shaped its history, and ultimately how the past provides the context for the present, and for the future, of this unique City."

Camila Hampshire, Museum Manager and Cultural Lead at the Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Art Gallery, said: "The project has brought out the potential of Exeter's archaeology collection that have been stored at the RAMM for many years. The museum can now bring the new discoveries and the science behind them to a wider audience."

The research is published in two books the first of which, "Roman and Medieval Exeter and their Hinterlands: From Isca to Excester," is published by Oxbow books this month. A companion volume, "Studies in the Roman and Medieval Archaeology of Exeter," will be published later in March. Both will be available as both an open-access downloadable PDFs and in print form.

R.C.