Using a technology called mantle tomography — akin to a CT (computerized tomography) scan of Earth's mantle — a team of geologists identified a rock slab under the crust of northern Canada that could be a remnant of the Resurrection plate. They then used 3D imaging technology to unfold and raise this "Yukon slab" back to the surface while winding back the geological clock. They found the Resurrection plate neatly plugged a gap between two known plates, the Kula and the Farallon, and also aligned with volcanic belts along the coasts of Alaska and Washington that typically form at plate boundaries.

The tomography technique used to resurrect the Resurrection plate could be a useful tool for finding other disappeared plate boundaries, according to the authors. These rediscovered boundaries could, in turn, help identify new volcanoes and mineral deposits and even refine models of past climate.

A New Tool for an Old Debate

Geologists' debate over the Resurrection plate has historically revolved around differing interpretations of a geological puzzle along North America's Pacific coast. A volcanic chain along the coast of Alaska seems to have formed around the same time as, and through a process similar to, a volcanic chain along the coast of Washington and Oregon. The problem is, more than 4,000 kilometers (2,500 miles) separate these two regions. There are two possible explanations for this anomaly: Either these chains were once much closer and moved apart over time, or they were connected by a shared plate boundary that no longer exists.

"We were sort of stuck at this point where there was a lot of argument about whether or not certain rocks have been translated long distances, and it was pretty hard to move forward," said Michael Eddy, a geologist with Purdue University who was not involved in the research.

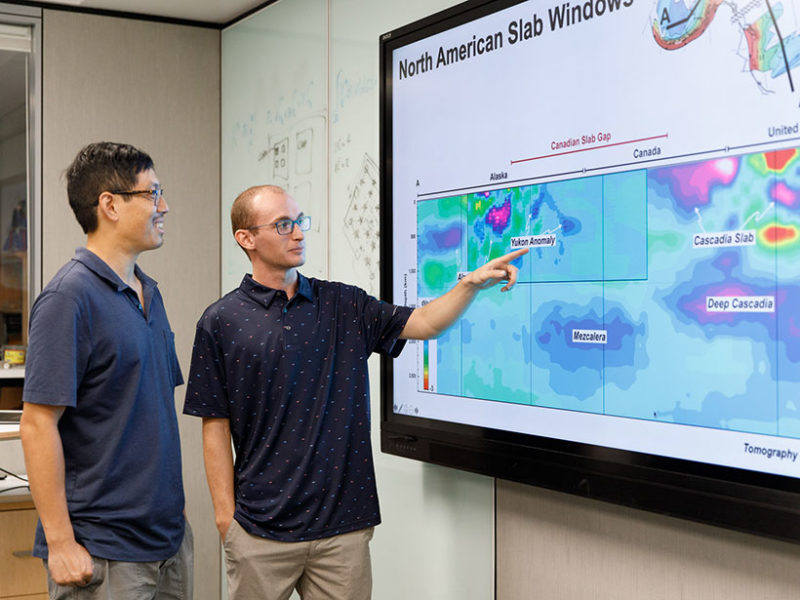

Mantle tomography offers a new line of evidence for this old debate. The technology analyzes seismic waves produced by earthquakes or explosions, reconstructing a 3D image from the way the waves reflect, refract, and change their speed as they move through Earth's solid layer of crust and upper mantle (lithosphere).

"It essentially looks like a heat map of Earth's mantle," said Spencer Fuston, a geologist at the University of Houston and lead author of the paper. Subducted rock from Earth's crust is cooler than its surroundings, and tomography can locate these cooler slabs. The Resurrection plate debate provided the perfect testing ground to see whether tomography technology had reached the point where it could help identify lost plates.

Finding the Missing Puzzle Piece

To get their geophysical evidence, Fuston and principal investigator Jonny Wu, another geologist with the University of Houston, first used tomography and 3D modeling to pull out known plates. These plates once formed the bottom of the Pacific Ocean but have now largely been folded under North America. "When we did that, these two reconstructed plates had a big gap in the middle where we couldn't account for any subducted ocean lithosphere. That is, until we looked below northern Yukon," Fuston said.

That's when they found the Yukon slab, completely buried below the continent. When the researchers added this slab to their model, it fit like a missing puzzle piece, providing the most direct evidence yet that the Resurrection plate once existed.

"What I really appreciated about their work is they tried very hard to integrate their geophysical study with the surface geology we've been looking at for decades," Eddy said. "This is the sort of thing that's going to really push the field of tectonics forward."

"The idea was, if we could get it to work here, we could probably find many new disappeared plate boundaries around the Earth throughout history," Wu said.

Tomography could also help scientists better understand volcanism in Panthalassa. "When we're looking at understanding climate change in the ancient Earth, understanding these anomalous volcanoes is very helpful," Fuston said. "And understanding ancient climate change is really the key to understanding and forecasting modern day climate change."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter