On 29 October 1945, the New York City branch of Gimbels department store unveiled a new product. Billions upon billions would follow in its wake.

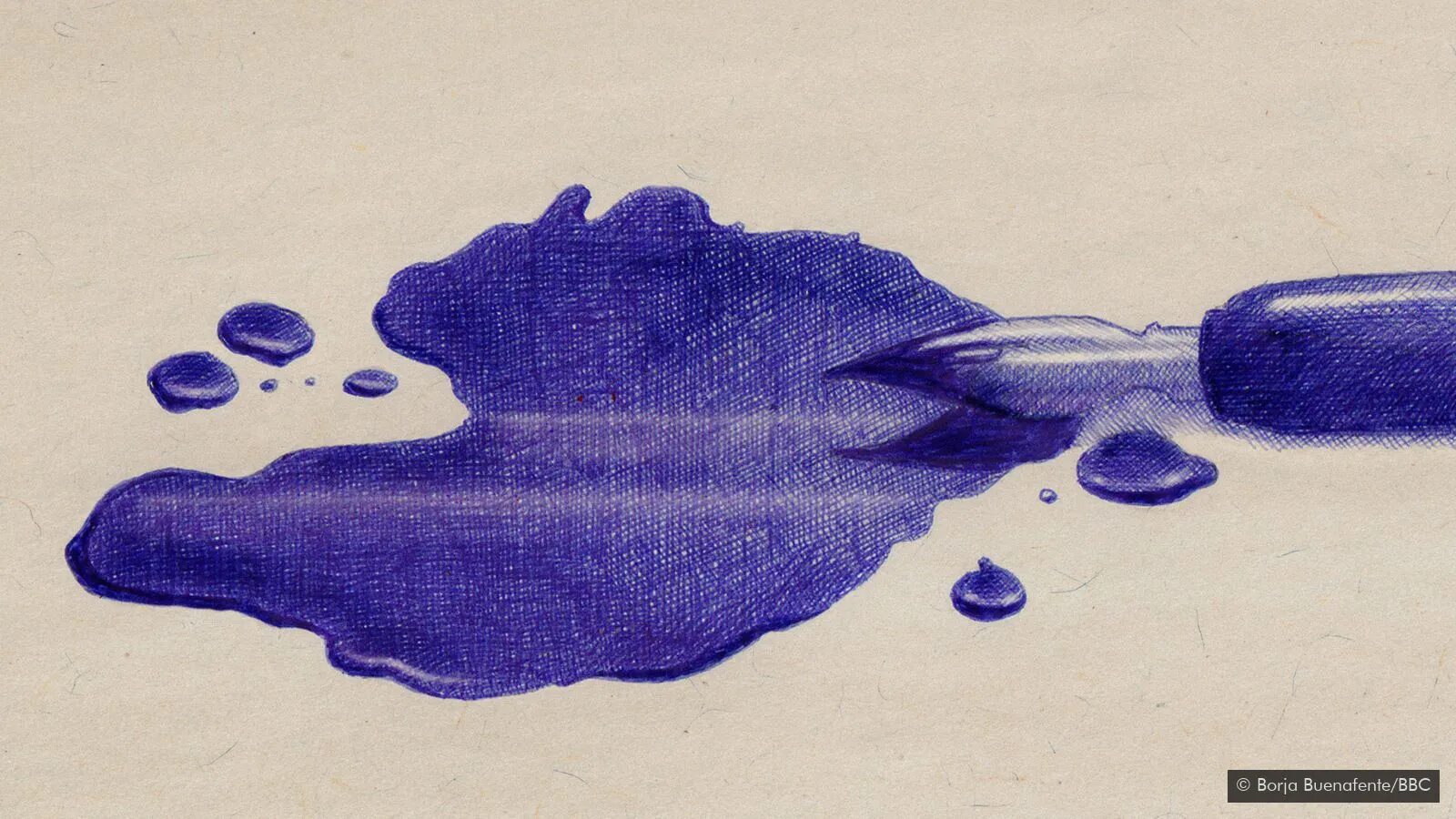

Gimbels was the first to sell a new kind of ink pen, the design of which had taken several decades to come to fruition. The pens, made by the Reynolds International Pen Company, promised an end to the messy mishaps users of fountain pens encountered - leaking ink, smudges and pooling ink blots.

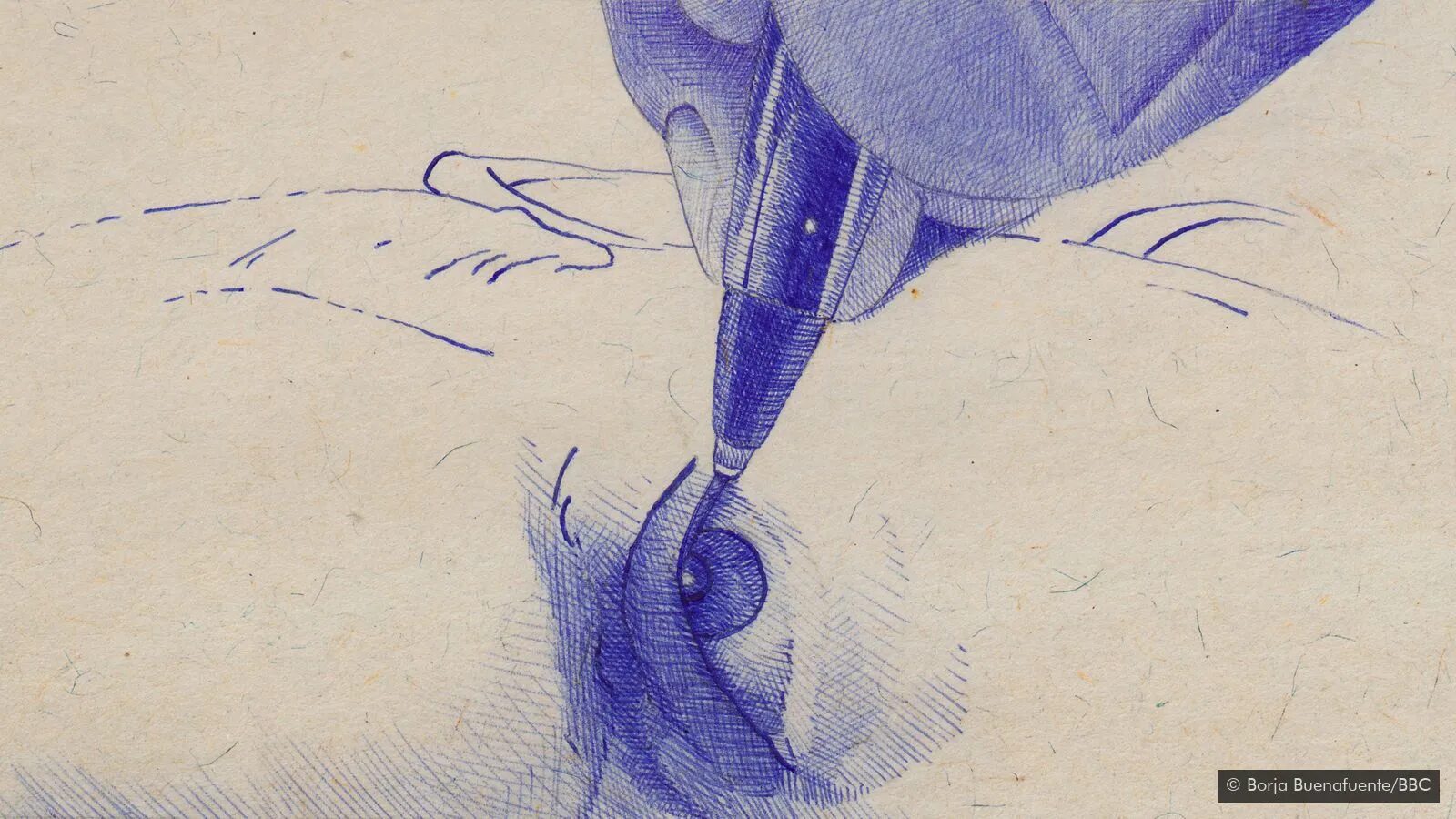

The new ballpoint pens did away with this, using a special viscous ink which dried quickly and didn't leave smudges. At the heart of it, the rolling ball in the nib - and gravity - ensured a constant, steady stream of ink that didn't smear or leave solid pools of ink on the page.

The new ballpoint was clean and convenient. What it wasn't was cheap.

The new Reynolds ballpoint cost $12.50 - convert that to 2020 money and it's more than $180 (£138.50). Today, if you were buying your pens in bulk, from stack-'em-high superstores, you could end up with more than 1,000 for the same price.

The pen was the first to go on sale in the US, but it was by no means the first ballpoint pen - the head of the US company that made it had in fact discovered a version during a business trip in South America. Its evolution is, in many ways, an example of a game-changing design waiting until outside factors - in this case the rise of plastics and mass-production infrastructure, and a brilliant marketeer - allowed it to achieve its full potential.

Loud, then quiet

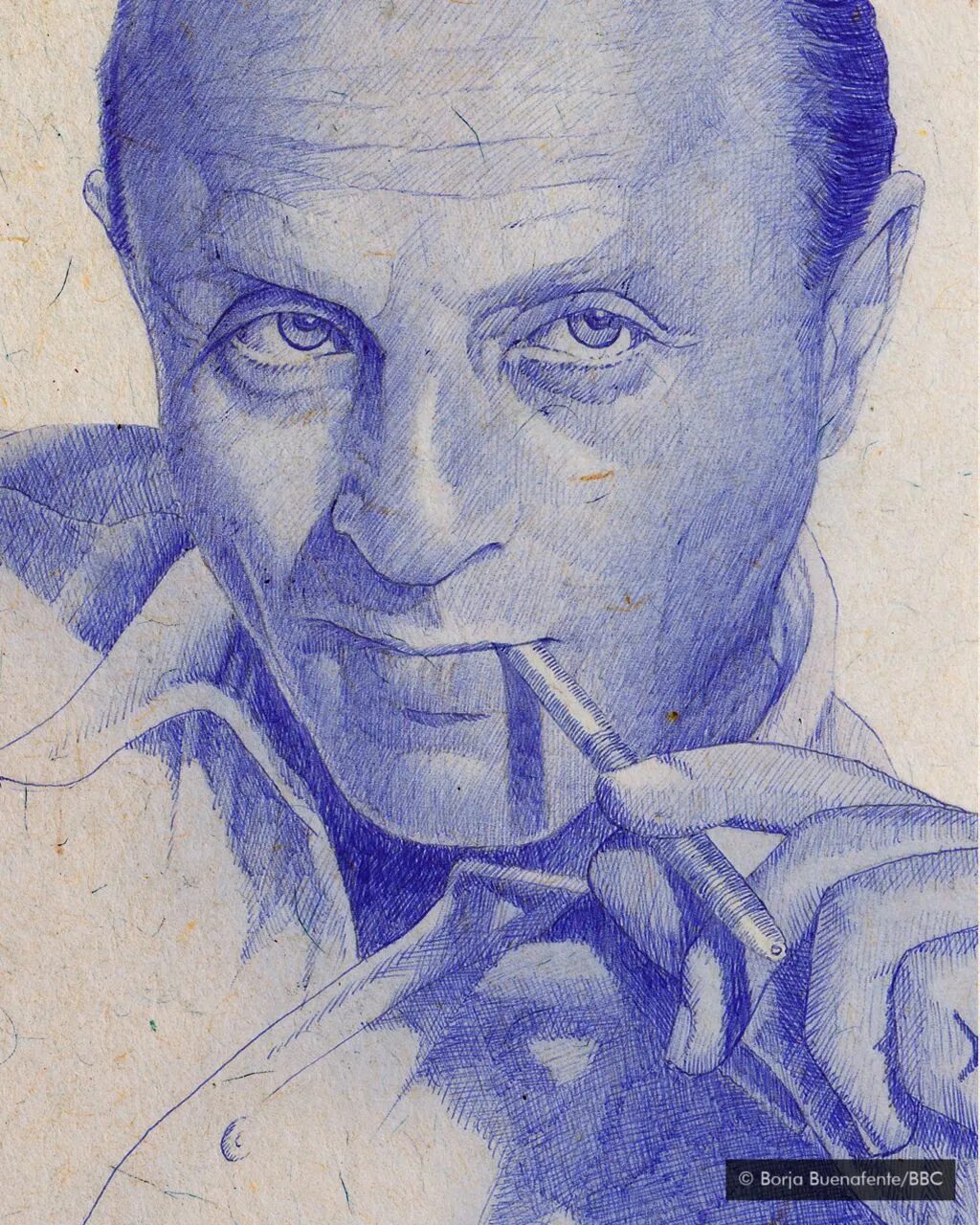

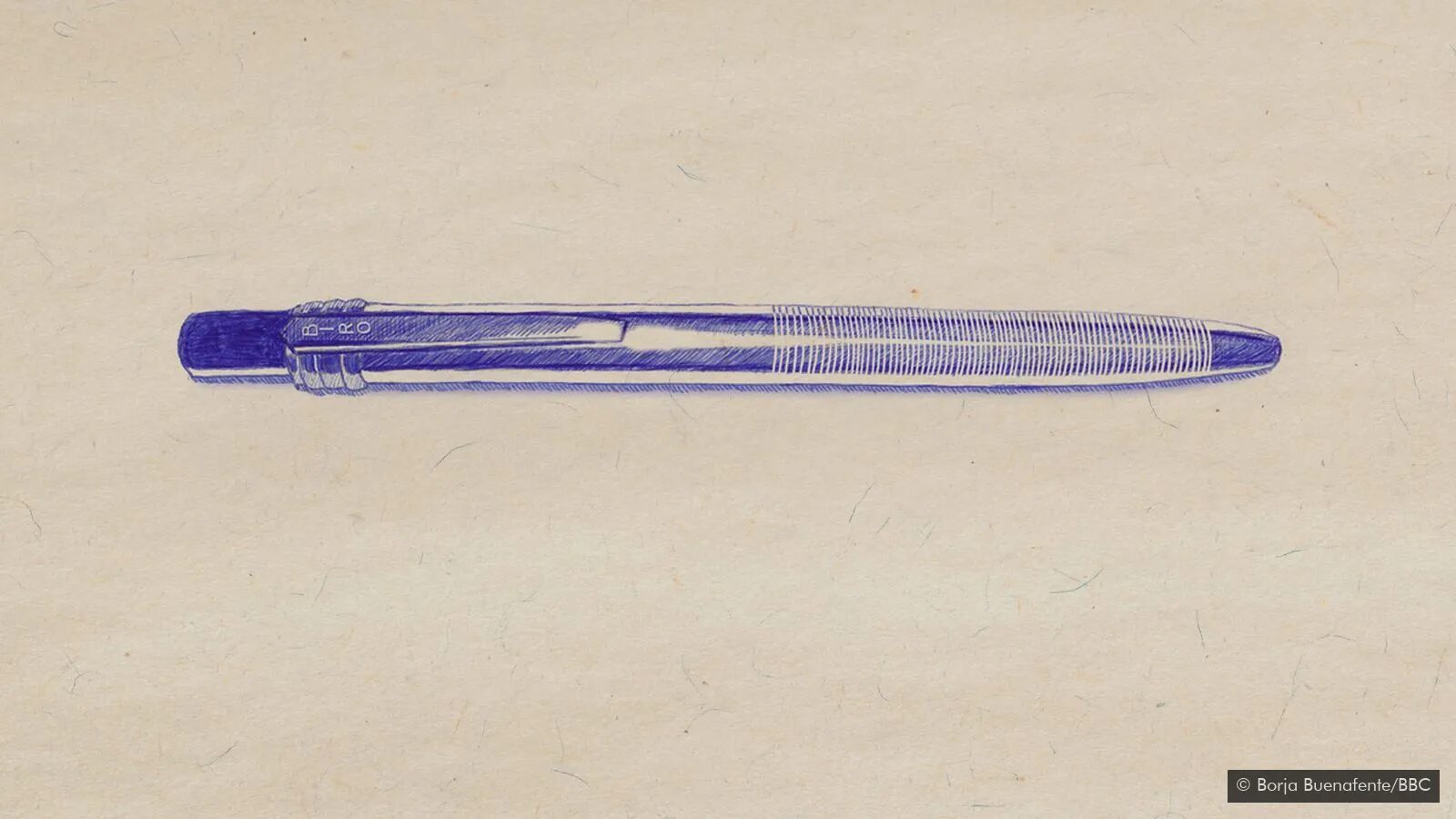

The creation of the ballpoint pen is usually credited to a Hungarian-Argentinian inventor László Bíró, whose name inspired a catch-all term for modern ballpoints. But it is, in fact, a lot older.

An American, John J Loud, received the first patent for a ballpoint pen back in 1888. Loud, a lawyer and occasional inventor, wanted an ink pen which would be able to write on rougher materials such as wood and leather as well as paper. His masterstroke was the revolving steel ball, which was held in place by a socket. In his 1888 patent filing, he wrote:

"My invention consists of an improved reservoir or fountain pen, especially useful, among other purposes, for marking on rough surfaces-such as wood, coarse wrapping-paper, and other articles where an ordinary pen could not be used."Loud's pen was indeed able to write on leather and wood, but it was too rough for paper. The device was deemed to have no commercial value and the patent eventually lapsed.

Various inventors tried to improve on Loud's design in the coming decade, but none were able to take it into production until Bíró in the 1930s. A journalist in Hungary, Bíró used fountain pens daily and was very familiar with their drawbacks.

"He was used to the fountain pen which was very leaky and left ink on your hands and smudged and he was very frustrated by it," says Gemma Curtin, a curator at London's Design Museum.

Simply adding fountain pen ink to a ballpoint pen was not the solution, however. The ink itself needed to be rethought.

László turned to his brother, Győrgy, a dentist who was also a talented chemist. László had realised the ink used in fountain pains was too slow to dry and needed something more like the ink used on newspapers. Győrgy came up with a viscous ink which spread easily but dried quickly. What's more, the pen used far less ink than the spotting, dripping fountain pens.

"Other people had thought of it before, but it was down to him, working with his brother - who was a good chemist - and getting the texture of the ink right," says Curtin. "It is very like printer's ink, and it doesn't smudge."

The principle at the heart of the ballpoint pen mimics the action of a roll-on deodorant - gravity and the force applied smear the rolling ball with a continuous stream of ink as the ball rolls along the writing surface When the pen isn't used, the ball sits tight against the end of the ink reservoir, preventing air entering and drying out the ink. Most often, ballpoint pens run out of ink long before they dry out.

The first "birome", as it became known in Argentina, was released in 1943, while war was still raging in Europe and the Pacific. The design piqued the interest of the Royal Air Force (RAF), who put in an order for 30,000: the pens were able to be used by aircrew at high altitude unlike fountain pens, which tended to leak because of the pressure changes. Otherwise, the original pen was little-known outside its South American home - the few original models current all for sale on online auctions all hail from Argentina.

In 1945, two US companies - the Eversharp Co and Eberhard Faber Co - teamed up to licence the new pen for the US market, having spent half a million dollars ($7.2m or £5.6m in today's money) to sew up the rights to North and Central America. But they were too slow on the draw. American businessman Milton Reynolds was visiting Buenos Aires and was impressed with the new pen - he bought several, and on return to America set up the Reynolds International Pen Company to market a new design.

Crucially, the Reynolds design had enough changes to sidestep László Bíró's patent, and was the first to go on sale on October of that year. It was, almost instantly, a must-have accessory. As Time magazine reported, "thousands of people all but trampled one another last week to spend $12.50 each for a new fountain pen", noting that the new pen only needed refilling once every two years. Gimbles had ordered 50,000 of the new pens and had sold 30,000 of them by the end of the first week. According to Time, Gimbles made more than $5.6m in sales ($81m or £62m in 2020) from the new pen in the first six months.

The biro might now be regarded as an everyday, almost disposable object, but it's worth taking a step back and appreciating the no-mess simplicity of its operation, says Curtin. "It's one of those design stars that everybody loves."

The first generation of ballpoint pens mimicked the style of fountain pens. They were made of metal and intended to be refilled with ink. The Reynolds pen made a big point out of its ability to write for two years without needing to be refilled, worlds away from the experience of using a fountain pen. Ballpoint pens might not have had quite the bookish cachet of fountain pens, but they were still seen as a desirable object. If you wanted a truly cheap writing implement you used a pencil.

But this created a problem. So many companies - including Eversharp and the fountain pen maker Parker - jumped on the ballpoint bandwagon that the market became saturated. People bought refills, but they didn't buy more pens.

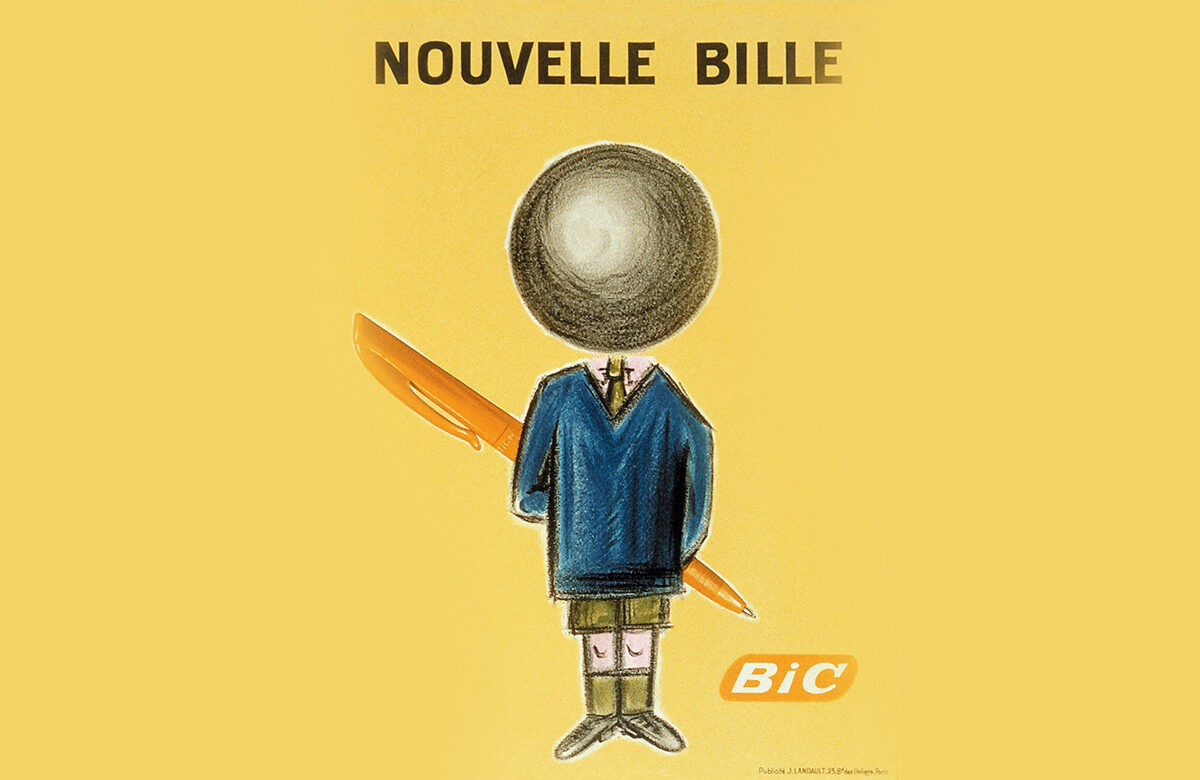

The masterstroke which would change the ballpoint pen forever came not from the US but from France. Michel Bich was an Italian-born French industrialist who ran a company making ballpoint pens. "No one understood better than Marcel Bich that potent 20th-century alchemy of high volume/low cost," ran his obituary in the UK's Independent newspaper when he died in 1994. "To this formula he added the magic catalyst of disposability. He invented nothing, but understood the mass market almost perfectly."

Bich realised the ballpoints so far had been premium products - an alternative designed to be regularly replaced could be a lot cheaper. Bich acquired a dormant factory near Paris and set about creating his new company, Societe Bic. An advertising executive had suggested the industrialists shorten his surname to create an instantly recognisable three-letter trademark. The company's trademark logo, the Bic Boy, had a smooth featureless orb as a face - a reference to the metal ball in the point of the pen.

The new pen had an equally dramatic effect on the act of writing itself, says David Sax, the Canadian journalist who wrote the book The Revenge of Analog. "The ballpoint pen was the equivalent of today's smartphone. Before then, writing was a stationary act that had to be done in a certain environment, on a certain kind of desk, with all these other things to hand that allowed you to write.

The ballpoint pen is testament, Sax says, to one of the tenets of "really great design - it almost disappears. If the ballpoint didn't exist and you launched one today on Kickstarter, it would be the biggest thing ever," he says.

One major reason Bich's cheap and cheerful pen took off was thanks to changes in production techniques. Plastic mass production allowed the new ballpoint pens to be made very cheaply. Over the following decades, the pens have become even cheaper, without compromising on their ability to write. "The basic, cheap example made by Bic works as well as it did 50 or 60 years ago," Sax says.

Author Philip Hensher, who also runs a creative writing course at Bath Spa University in the UK, wrote a 2012 book on handwriting called The Missing Ink in which he praised the ballpoint pen. He says Bic not only found the way to produce vast quantities cheaply, but crucially hit upon a winning design right from the start. "If you have a product that needs no improvement - only tiny changes have been made to the Bic pens since the 1960s - you probably don't have a lot of overheads."

Produced since 1950, the Cristal has sold in mind-boggling quantities: it notched up 100 billion sales by 2006. It is such an everyday object that its strengths are easy to overlook.

The hexagonal body makes it easy to grip; the "transparent shaft that allows you to see the ink running out", Hensher says. A tiny hole in the body equalises the air pressure both inside and outside the pen. Then there is the ink, drying in a couple of seconds instead of the 10s of seconds. "To be perfectly honest, the Bic pen is just such a miracle you don't even think about it anymore.

"You have to look, too, at the effect the Bic biro had on Africa," Hensher says. "It was marketed by Bic as something very modern. It really transformed African society. There just wasn't a way for people to write easily before the Bic."

The billions upon billions of cheap ballpoint pens made by various manufacturers since the 1950s have another lasting legacy, however, and this one is less heralded. Their disposable nature has created an enormous amount of plastic waste. More than 1.6 billion are thought to be thrown out every year in the US alone.

"Those 100 billion ballpoint pens sold are probably all still in landfill," says Curtin, noting that in most cases the pens' bodies themselves are perfectly able to be reused again and again. "Just because the ink has run dry, we throw the whole thing out. That's quite strange."

Ballpoint pen manufacturers are aware of this plastic pollution crisis. Bic themselves make a range of pens produced from 74% recycled plastic. More producers are promoting the idea of refills for plastic pens, and not just the metal ones that come with premium price tags. Other pen manufacturers have replaced the plastic body with tubes made of cardboard, or metal - the very material the first premium ballpoints were made of more than seven decades ago.

Our digital-first culture might celebrate screen over paper, but Sax believes the cheap ballpoint is here to stay. "When people in the tech world talk about outdated tech, they are never arguing that pens are outdated. Even Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk will have a bunch of pens sitting around."

I'm going to guess that they added diatomaceous earth.

Not gonna research, though.*Well, as re the ballpoint pens they extol so much, these days, at least, this is BS: R.C.

*I decided to. I do inventions, akin to the first inventor above. My bald guess IS RIGHT! RC