My space-cadet tendencies earned me the nickname "butterfly brain" when I was about 8 years old. Even as an adult, working from home, I can spend the day flitting from one thing to the next, doing nothing of any use at all. When that happens, I'll feel stressed and frustrated - and I'll have even more to do the next day.

Lack of focus and a susceptibility to procrastination are both hallmarks of a brain that is not under the proper control of its owner. I'm not the only one who struggles with this problem. In one recent survey, 80 percent of students and 20 to 25 percent of adults admitted to being chronic procrastinators. The evidence suggests that this behavior actually leads to stress, illness, and relationship problems.

Letting the mind wander off doesn't seem to make us any happier. In another study, researchers interrupted people during the day to ask what they were doing and to score their level of happiness. They found that when people were daydreaming about something pleasant, it only made them about as happy as they were when they were on task. The rest of the time, mind-wandering actually made them less happy than they had been when getting on with their work.

While I was banging my head on my desk in frustration one day, I remembered once interviewing Joe DeGutis, a neuroscientist at Harvard, for an article I was writing. I knew that cognitive training, and attention in particular, was his thing. So I e-mailed him to see if he might be able to sort me out.

DeGutis and Mike Esterman, of Boston University, run the Boston Attention and Learning Lab at the VA Medical Center. They had been working on a combination of computer-based training and magnetic brain stimulation (also known as TMS) to help people focus better. Their program seemed to improve people's ability to sustain attention, though, like in most neuroscience studies, they had only tried it on people with serious problems - ranging from brain injuries, strokes, and post-traumatic stress disorder to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. I couldn't help but wonder: might it work for me, too? Probably not, came the reply. But they humored me and sent me a link to a version of a sustained-attention test they use, and several questionnaires to measure things like how often I make silly mistakes because I'm not paying attention (quite often), and a "mindlessness" scale, which would measure how much I wander around in a daze (a lot).

I sent it all back to them, and the next day the cold, hard truth hit my inbox. I scored 51 percent on the attention test - a good 20 percent below average. And the questionnaires were pretty telling too. "Considering all your results, it's very clear that you have issues with attention and distractibility both in the lab and in daily life," wrote DeGutis. Then, to soften the blow - and aware that I was working on a book proposal on the subject - they invited me over from the United Kingdom to see if they could help. No promises, but they'd do their best.

A month or so later, DeGutis and Esterman take me down to a disused hospital room at the VA that was last decorated in bright orange around 50 years ago. There is a huge black chair where the bed should be, an ancient X-ray viewer, and two clocks that clearly haven't ticked in years. The chair is part of the TMS machine that they will be using to zap me in the head the following day.

First I've got two hours of assessments to get a baseline measure of my skills - or lack of them - in this particular week and a brain scan so they can map out which region they want to stimulate. I start with a test Esterman has nicknamed "Don't Touch Betty." My task is to look for the only female face ("Betty's") among a constant stream of male faces as they fade into each other at the rate of about one a second. When I see a male face I press a button, but when Betty pops up I "don't touch." It sounds easy, but the faces are all black and white and surrounded by black-and-white scenes of mountain- and city-scapes, which fade into each other at different speeds to the changing faces. The test lasts for 12 minutes, but it feels much, much longer. I'm finding it not so much difficult as physically impossible. Even when I spot Betty, there never seems to be enough time to tell my hand not to press the button. I spend the whole 12 minutes berating myself as Betty's Mona Lisa smile starts to look more and more mocking. In fact, I'm convinced that the researchers will wonder if I even understood the instructions when they look at my results.

One test measures my brain efficiency, or how quickly my attention circuitry can reset itself and spot something new. Other tests help them work out which side of my brain I tend to use more to pay attention, and how easily I am distracted by something in my peripheral vision, like an e-mail notification on the screen or a bird flying past the window.

Then they put me in a magnetic resonance imaging scanner to get a 3-D picture of my brain. We head downstairs to a white room where the MRI scanner is kept. The technician hands me an enormous paper trouser suit. They pack me into the scanner with earplugs and a foam neck brace, and I promptly start to doze.

Their main area of interest is called the dorsal attention network, which links thinking areas toward the front of the brain to the parietal cortex, which lies above and slightly behind the ears and acts as a kind of switchboard for the senses. Both sides of the brain have a version of this network, but realtime imaging studies suggest that most of the work is done by the right side. People who struggle to sustain attention, though, often have more activity in the less efficient left side.

DeGutis and Esterman tell me I am going to do three rounds of 12-minute training, twice a day for a week, with extra sessions on two of the days following the brain stimulation. To be honest, the training is pretty boring. Much like the Betty test, there is a target image on the screen that you don't press the button for - say a white cup on a brown table - though you do press for any other cup-table combination. On my first attempt, I get only 11 percent of the "don't touches" correct. They adjust the training as needed - making the target appear more or less often, for example, or flashing the pictures at more regular intervals - in order for me to get 50 percent correct. Only when I hit that magic number can they start to improve my skills.

The next morning is zapping day, and I wake up excited about seeing my brain for the first time. We head up to the room with the big chair in it - and there it is, large as life, on an enormous screen. My brain. I'm not sure what I was expecting, but it all looks fairly normal, lumps in all the right places and no obvious holes that shouldn't be there. Esterman has overlaid the position of the dorsal attention network with the image of my brain, marking the area he is going to target.

I had assumed that the plan would be to jolt my brain into working better, but it turns out to be the opposite. The plan is actually to knock out activity in part of the left side of the attention network, using targeted magnetic pulses, to force me to use the right - the one I should be using anyway. The idea is that the right side will eventually become strong enough to take over from the left in everyday life, in a self-perpetuating cycle.

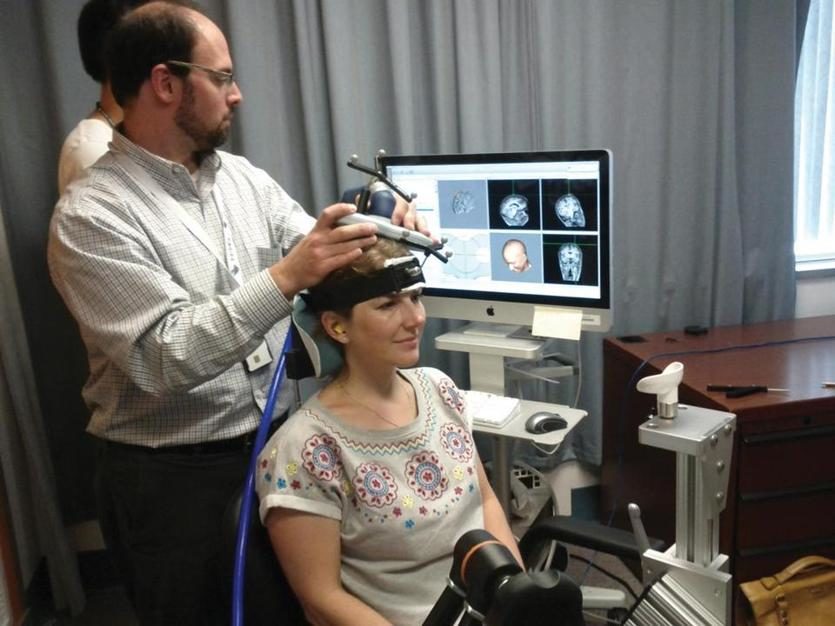

Strapped into that chair, I look ridiculous, wearing a tight headband with what looks like a coat hook on the top. Research assistant Hide Okabi tells me it's basically an expensive version of a Nintendo Wii, linking your movements in real life to what is happening on the screen version of you. So when Esterman moves the magnet over my head, he will be able to see on the screen where in my brain he is aiming.

It feels seriously weird; my hand clenches in front of my eyes as if someone is pulling it with strings. It doesn't hurt, but the hit of electromagnetic energy feels a lot like someone flicking me pretty hard on the head once a second, in time with a loud click. At first, it's just a light tap, but five minutes later, it has become very annoying. I'm starting to feel a bit lopsided. I'm supposed to have three eight-minute sessions of stimulation, but when I admit to feeling a bit dizzy, they decide that two is probably enough.

After the zapping, I do another session of DeGutis's training and it soon transpires that, with or without brain stimulation, the training is just as frustrating. I do even worse at the tests, and I can tell that Esterman is a bit perturbed. He's not saying much, but it seems that he expected me to do better after a short, sharp zap.

By day three, I am still not improving, and I am so frustrated I feel like yelling every time I hit the space bar in error. I have no trouble spotting the target; in fact, I see it straightaway. But it feels as though a gun to my head couldn't stop me from pressing the space bar. The researchers are looking even more frustrated than I am - and a bit worried, too. DeGutis later confesses that he was scared I'd go write about how his training program is "the dumbest thing ever."

But then, out of the blue, sometime between morning and evening training on day three, something clicks. My score jumps from between 11 percent and 30 percent correct "don't touches" to 50 percent to 70 percent. What's more amazing is that I'm starting to enjoy it. And when I accidentally make a mistake, I have a strange understanding of where my mind went. I realize, for example, that I got one wrong because I was wondering what my son was up to back home. In another lapse of attention, I was wondering whether I should have wine or beer after the training.

By the next day, I am doing it one-handed, while casually grabbing for my cup of tea with the other hand. DeGutis seems excited by this - and tells me it could be an important development. Being aware of what you are thinking is known in psychology as "meta-awareness," and it's essential if you are trying to spot mind-wandering before it takes you too far away.

And it might be my imagination, but I feel a lot calmer, too. Normally I procrastinate when I should be working, and, as a result, I end up working - and stressing - in what is supposed to be relaxation time. But this week I'm a journalistic ninja: I do all of my work in the allotted time slot, then have a great time catching up with friends in Boston, with no guilt or stress about work not being done. It might not sound like much, but it's a revelation to me. Maybe life doesn't have to be so stressful after all.

I also noticed a few more subtle changes outside work. On day two in Boston, I moved out of the hotel and went to stay with friends for the rest of the week. This normally would have caused me to get in a right old state. Even with good friends and close family, I am an anxious houseguest, unable to relax because of the nagging feeling that I'm in the way, or that I should be doing more to help with the cooking and cleaning, or that I should be making better conversation. I even worry that my worrying is stressing everyone out. But not this week. This week, it's all good.

Aside from confirming that there is room for improvement, and that I probably don't have ADHD, the researchers are saying nothing until I re-sit the Betty test on Friday. Keeping experimental subjects in the dark is part of how science works: The more I know, the more likely my expectations will skew the results. All I know is that training has now become easy and that the butterfly feels under control for the first time in a long, long time.

Mind-wandering must have evolved for a reason - most probably for hunting and gathering purposes; a state of mind that allows you to scan the surroundings, waiting for something interesting to crop up, is useful in an unpredictable environment. Nowadays, it serves us well when we are casting around for ideas or just need a mental break. On the other hand, focusing hard is too exhausting to keep up for long, so the best way to sustain focus over minutes to hours is to turn it down a little bit - let the mind wander when it wants to but not too far before bringing it back.

Comment: The 'purpose' for mind-wandering may be quite different than what is commonly assumed. See:

Regular breaks are often touted as a way to help focus, since "alertness cycles" in the brain supposedly give us about 90 minutes of alertness before zoning out for a while to reset. Other psychologists argue that it is more likely we pay attention quite literally using a reserve of mental energy, eventually running out of funds. Then there's mindlessness theory, which says that loss of attention happens when the brain gets so used to the task that it shifts into automatic mode, essentially taking focused, effortful attention elsewhere. For me, the trouble with all of these solutions is that they require not only a certain amount of mental control but a lot of organization, and that's not always easy when you're already battling a limited attention system. Plus, what I'm trying to do in Boston is to make such strategies redundant by fundamentally changing the way my brain uses its attention resources.

So did all that training and zapping really do anything to my brain? Well, the short answer seems to be yes. My score on the Betty test showed a huge jump, going from 53 percent incorrect before training (worse than any other healthy person they had tested, and in the region of a brain-injury patient) to 9.6 percent afterward (almost as good as the best healthy person in the same study).

DeGutis was as amazed as I was. "We were like, 'What? Did we run the same version of the test? That's remarkable,'" he says. But they checked, and it was indeed exactly the same test. This time, it felt as if I had all the time in the world to spot Betty. And when she came on the screen, she didn't smirk before disappearing - instead, she gave me a friendly smile, as if to say "Hi" before slowly fading away. A few times, I even smiled back. Everything felt as if it were happening in slow motion.

Have I really changed my brain in just one week, after only four hours of boring but fairly easy brain training and a side order of stimulation? "Not structurally," say Esterman and DeGutis in unison, keen to rid me of any notions that they have rebuilt my brain. "But functionally, how you engage the brain . . . something is different," says Esterman. That means that while I might not have wired in a completely new circuit, the one I already have might be working more efficiently. In a way, that's even more exciting because it means that you don't have to make huge structural changes to the brain to fundamentally change the way it works and - crucially - the way you experience life.

Perhaps I started using the same basic circuits more efficiently by engaging the right side of the network more, or by doing a better job of nipping my wandering mind in the bud. According to the laws of brain plasticity, over time, this might add up to larger areas of brain tissue and more connections between different parts of the dorsal attention network. Eventually, it might become part of who I am, just like my butterfly brain is now.

Could focusing better be a simple matter of getting into a relaxed state of mind, concentrating, and letting the mind wander occasionally? It seems so.

"If you're always on then you can grind yourself into a little nub," DeGutis says, "and you're fighting yourself the whole time and you do worse work."

Then DeGutis gives me the bad news. My newfound calm almost certainly won't last unless I do something to keep it going. Just like physical exercise, you have to keep at adult brain training or you'll end up as flabby as before. "The dose you had will probably last two or three weeks," he says apologetically. DeGutis and Esterman are more than happy to admit that they still don't exactly know what the training does to the brain. In fact, they have never tried this on someone who didn't have serious brain problems, and they are as interested as I am to see how I get on after I get home.

So did I keep the calm, even when the demands of juggling a young child, work, and chores kicked back in? Actually, yes. For a few weeks, I felt as relaxed and focused as I had during my stay in Boston. Life was good - easy even. Things that previously would have sent my concentration running for the hills, like playing Lego with my son when I had a million jobs to do, were actually pretty enjoyable. Afterward, I at least could remember what it felt like to be in the zone that I had practiced in Boston. Thankfully, it turned out that there are other ways to get the same effect.

One of the best options is meditation. It shouldn't be much of a surprise - after all, Buddhist monks have been working at sitting still and being calm for centuries. But meditation has always sounded a little too new age for me. And, seriously: Who has the time? Sara Lazar, a neuroscientist at Harvard Medical School, has spent years studying the effects of meditation on the brain and has found that long-term meditators have lower activity in a region of the brain called the posterior cingulate cortex, part of the default-mode network that controls mind-wandering. She recommends 10 minutes a day - but every day. Even after an eight-week course of mindfulness meditation, she tells me, there are changes in the brains of total beginners. Yoga is almost as good, apparently, and since I do that at least once a week, I am already at least some of the way there. Lazar suggests maybe doing 20 minutes of yoga every day instead. I manage it for about a week, and then the good intentions start to wear off.

One other option, though, has proven much easier to keep to, because it involves almost no effort.

In studies, people were able to rejuvenate their attention simply by spending a few minutes looking at a picture of a natural scene. Other studies show that it works even better if you exercise at the same time. Looking at city scenes had no such effect. Luckily, I've recently taken on a restless sheepdog puppy who needs a lot of running around outside. Now, whenever my brain starts to misbehave, I stop what I'm doing and take him for a stomp through the woods. So far, nine times out of 10 it does the trick.

Caroline Williams is a writer based in England whose work has appeared in New Scientist Magazine, The Guardian, and the BBC. This story is excerpted from her new book, My Plastic Brain: One Woman's Yearlong Journey to Discover If Science Can Improve Her Mind, published 2017 by Caroline Williams.

Notice Caroline said she needed meditation and visualization of nature to set the stage for focused attention. Men are hardwired for this by hormonal chemistry, apparent in crisis or emotionally charged situations, and are more adept at setting aside emotion in order to be task focused the more the father has influenced the early personality development.

In Expendables 2, Maggie asks Barney: "Do you think about the young man who died?"

Barney: "All the time."

Maggie: "You don't talk about him much."

Barney: "No, that's how we deal with death. Can't change what it is, so we keep it alive until it gets dark. Then we get pitchblack. Understand?"

Training, Discipline. Ordered attention. A time and place for non-damaging emotional expression.

Yoda's complaint about Luke, the fatherless Jedi wannabe: "Never his attention on where he's at!"

What is it the Feminists complain about most? That women lament the most? Males instilling order, predictability, security, competency, leadership.