Daydreaming need not be the enemy of focus. Learn to do it right and you could reap the benefits from more successful revision to more motivation

Your exams start in less than a month. Or there's that make-or-break meeting next week that you need to prepare for. But no matter how hard you try to focus, you just can't. The clock is ticking, but the sun is shining and, oh, is that a barbecue you can smell?

If losing concentration sometimes feels inevitable, that's because it is - your brain is hardwired to give in to distractions and take you away with the fairies. To make matters worse, science has long backed up the idea that a wandering mind is the enemy of productivity. Failing to focus has been linked to lack of success, unhappiness, stress and poor relationships. It's enough to make you give up and head for the beach you were just daydreaming about.

But don't. Recently, psychologists have been having a rethink. If we spend so much time in a state of reverie, they reason, it's probably not some psychological mistake. It turns out that there are several kinds of mind-wandering, and they don't all make you unhappy or unproductive. A wandering mind could even be a key weapon in your cognitive arsenal - if you know how to use it.

To master mind-wandering, you first need to understand what's happening in the brain when you try to pay attention. Broadly speaking, we have two attention systems that constantly keep track of what's going on around us. One, the bottom-up system, snaps our focus to anything that stimulates the senses: a loud noise, an email notification or someone tapping you on the shoulder. It may be annoying, but this ancient skill evolved for a reason - it's no good focusing well enough to knap the perfect spear tip if you get eaten by a lion before you can use it. Ignoring such disturbances is physically impossible, so the only way to stop them from hijacking an otherwise productive day is to shut them out: eliminate unpredictable noise, turn off email notifications, disconnect Wi-Fi.

Even these extreme measures won't stop the brain's goal-directed system from leading you astray. This helps you focus on the task at hand. It involves a constant tug of war between the executive control network, a set of brain areas responsible for goal-oriented thinking and controlling impulses, and the default mode network, which fires up when we think about nothing in particular. The default network uses this time to do various bits of housekeeping - sorting through memories, forward planning and filing new information, for instance - but it is also the brain region that is most active when we daydream.

Our ability to stay on track largely depends on keeping the volume of this chatter low. Too much activity in the default mode network, or too little executive control, leads to a mind that is prone to losing focus.

The problem is, the brain seems pre-programmed to find mind-wandering easier than concentrating. Recent studies have shown that the default mode network is highly connected to itself and other brain regions, allowing it to flit between many different mental states with little energy input. The executive control network, however, is more sparsely connected, so requires more input to shout over the noise. This might explain why, even on a normal day, we spend as much as 50 per cent of our time thinking about anything except what we should be doing.

Deliberate drifters

Given that a wandering mind has been considered a fast-track to failure, that sounds bad. But there are advantages to a propensity to drift off. We already know, for instance, that daydreaming brings numerous benefits to do with creativity and forward planning (see "Free your mind"). Now we are starting to see that those benefits extend even further, after figuring out a flaw in previous research.

Until recently, researchers assumed that volunteers asked to do a boring task in the lab would try their hardest to concentrate until mind-wandering unintentionally took over. What they failed to consider is that sometimes we intentionally let our mind drift to more appealing topics, especially when doing something boring.

In one experiment, Paul Seli, a psychologist at Harvard University, interrupted people during a task to ask whether their minds were wandering. If they were, he asked whether it had happened intentionally, or if their thoughts had just drifted unconsciously. He found that more than a third of the time, the mind-wandering was intentional.

Comment: Given the low level of self-awareness in the general population, one has to be wary of self-reported intentionality. "I did it on purpose," is often a stand-in for "I don't actually know why I did that".

Questionnaires asking people about their daydreaming habits put the number even higher - suggesting that more than half the time it starts off as a choice. "A considerable portion of our time seems to be spent off in la-la land and it seems that a high proportion of that is the deliberate type," says Seli.

To find out what's going on during intentional and unintentional mind-wandering, Seli and his team last year imaged the brains of people who tended towards one or the other, and found that their brains are set up slightly differently.

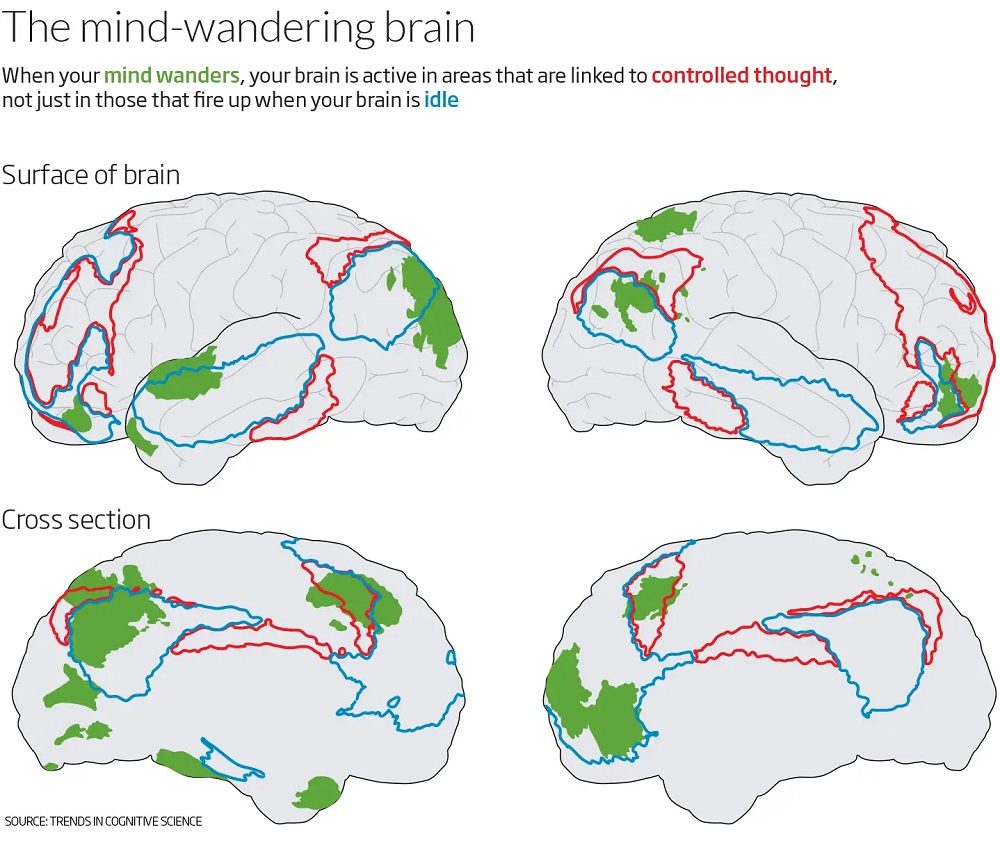

Both groups did about the same amount of mind-wandering overall, but those who were prone to doing it intentionally had better connectivity between their brains' executive control and default mode networks.

This suggests that with intentional mind-wandering, rather than the executive control network losing its grip over the default mode network, it was actually in charge of the whole experience. So it feels like daydreaming, but you are still in control of your mind (see diagram).

The distinction between these different styles is important. In the past, mind-wandering has been linked with some of the symptoms of ADHD and obsessive compulsive disorder, both conditions in which a lack of control over certain behaviours can interfere with getting things done. But the latest studies show that this is true only of unintentional mind-wandering, not the more directed kind.

Deliberate mental meandering might also help you remember more when you revise. The trick is to make your mind wander on topic, by nudging your thoughts to things you are trying to learn. One way to make this happen, according to Karl Szpunar of the University of Illinois at Chicago, is to build mini quizzes into the revision process. In his experiments, students learned the contents of a 40-minute lecture either by stopping to recap what they had covered every 5 minutes, or by rereading the slides at the end. Those who regularly self-tested retained more information.

Both groups seemed to mind-wander the same amount, but a second experiment showed that what was different between the groups was that the self-testers were mind-wandering about the lecture, as opposed to something unrelated. "Rather than waiting to self-test the night before an exam, make time to do this again and again at increasingly longer intervals," suggests Szpunar. This doesn't only apply to exam revision, he says, but any kind of learning.

"Deliberate mind-wandering can help you remember more when you revise"

Another way to maximise the benefits of your wandering mind is to dream about the future, says Jonathan Smallwood, a psychologist at the University of York, UK. He has found that whether our mental meanderings are focused on the future or past determines whether they derail us from our goals or prepare us for challenges to come.

Thoughts about the past are much more likely to lead to low mood and motivation than those about the future. By contrast, future-related mind-wanderings actually seem to boost mood and motivation, even if they are thoughts of flunking out. As long as there is a future element, says Smallwood, it can at least motivate you back to work.

Taking charge of the content of your thoughts might seem difficult when you feel you have lost control of your ability to focus at all. But there are tricks you can use to veer your mind towards the more useful, deliberate kind of wandering. Seli's research has show that people who have the trait of mindfulness - the natural ability to focus on the present moment - have a tendency to deliberately mind-wander. He thinks that the rest of us could learn such focus through mindfulness meditation and turn our unintentional mind-wandering into the more helpful, deliberate kind.

The problem is that mindfulness takes time to learn, which might rule it out if you're nearing a deadline.

There is a simpler strategy. Rather than waiting until you are revising, try to practise some deliberate mind-wandering in your downtime. People who naturally do more intentional mind-wandering tend to do it in quiet moments, when the demands of their tasks are low. Intentionally trying to mind-wander when doing something brainless or easy - filing notes, making a cup of tea, having a shower - seems to help them keep on track when they really need to concentrate.

If this all sounds like hard work, take comfort in the finding that, sometimes, being unable keep our minds on the job happens because we are trying too hard to focus. Using fMRI scans, Michael Esterman and Joseph DeGutis at the Boston Attention and Learning Lab tracked brain activity as people tried to hold their attention on a dull computer-based task.

They found that people made fewest mistakes when there was medium activity in both our default mode network and the areas involved in executive control. Too much activity in the control network led to a hard focus that was impossible to sustain for long. Too much in the default mode meant people were unable to focus enough to do the task.

So rather than trying to concentrate at all costs, to get the most out of your limited attention span, try and hit the middle ground - what Esterman calls being in the zone. "Pooling all your resources is good when you want to do one thing transiently, but if you want to sustain attention, you want to engage just the right amount," he says. "The moments when you're out of the zone may also occur when you're over-engaging these attention mechanisms."

To get people used to the feeling of being in the zone, DeGutis has designed a cognitive training computer game. So far he has mostly tested it with people who have attention problems caused by ADHD or post traumatic stress disorder, but he plans to try it on those with typical levels of mind-wandering. The difficulty with making this an all-purpose app is that everyone's zone is different, so the training has to be tailored to each individual (see "Brain zap apps").

In the meantime, there is an easy alternative. Simple as it sounds, just reminding yourself not to focus too hard might do something similar, according to work by Christian Olivers of Vrije University in Amsterdam. He found that telling people to focus less hard on a boring task improved performance.

So if you are prone to zoning out, practise intentional daydreaming when you have some downtime, keep those thoughts on topic and look to the future. But if all else fails, you can find solace in Smallwood's latest findings. In work yet to be published, he has found that although frequent mind-wanderers are indeed worse than other people at focusing on the outside world, they were also much better than most at retrieving information from memory. So if the information is in there somewhere, let your mind wander free. Your grades might thank you.

Shortcuts to a focused mind

If you're prone to daydreaming, there are simple ways to stay on task

Give your mind more to do: Adding deliberate distractions - a jazzy border on a page or a bit of background noise - actually reduces distractibility, according to research by Nilli Lavie at University College London. Her "perceptual load theory" proposes that this works because attention is a limited resource, so if you fill all the attentional "slots" in your mind, it leaves no room for other distractions.

Bribe yourself: The prospect of a treat can keep people focused, but only when well-timed, studies show. Offering people small rewards throughout a boring task didn't stop them losing focus, but the promise of a larger reward at the end kept them alert. This approach probably works best with an accomplice to keep you from caving early, says Michael Esterman at the Boston Attention and Learning Lab, who did the research. "It's hard to fool yourself."

De-stress: You might think that an adrenaline boost would focus the mind, but stress stimulates the release of hormones, including noradrenaline, which bind to receptors in the cognitive control circuits. This in turn makes it harder for them to keep tabs on mind-wandering.

Get some zeds: A lack of sleep hammers mental performance in general, and reduces our ability to resist internal and external distractions. And there's an added bonus to getting enough sleep. It is important for consolidating memories. In fact, research suggests that if you have an hour spare before an exam, a nap could be a more effective use of that time than revising.

Doodle: In one study, people forced to listen to a tedious voice recording were able to remember more afterwards if they were allowed to doodle. But content is important. Doodling about something related to what you are trying to remember is more likely to qualify as intentional mind-wandering, which can help you focus on the task at hand (see main story). Don't be too elaborate, however - if your doodles become too engaging, the whole thing might backfire.

Comment: See also: