Fifty years ago next month, invitation-only audiences gathered in specially equipped Cinerama theaters in Washington, New York and Los Angeles to preview a widescreen epic that director Stanley Kubrick had been working on for four years. Conceived in collaboration with the science-fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, 2001: A Space Odyssey was way over budget, and Hollywood rumor held that MGM had essentially bet the studio on the project.

The film's previews were an unmitigated disaster. Its story line encompassed an exceptional temporal sweep, starting with the initial contact between pre-human ape-men and an omnipotent alien civilization and then vaulting forward to later encounters between Homo sapiens and the elusive aliens, represented throughout by the film's iconic metallic-black monolith. Although featuring visual effects of unprecedented realism and power, Kubrick's panoramic journey into space and time made few concessions to viewer understanding. The film was essentially a nonverbal experience. Its first words came only a good half-hour in.

Audience walkouts numbered well over 200 at the New York premiere on April 3, 1968, and the next day's reviews were almost uniformly negative. Writing in the Village Voice, Andrew Sarris called the movie "a thoroughly uninteresting failure and the most damning demonstration yet of Stanley Kubrick's inability to tell a story coherently and with a consistent point of view." And yet that afternoon, a long line -- comprised predominantly of younger people -- extended down Broadway, awaiting the first matinee.

Stung by the initial reactions and under great pressure from MGM, Kubrick soon cut almost 20 minutes from the film. Although 2001 remained willfully opaque and open to interpretation, the trims removed redundancies, and the film spoke more clearly. Critics began to come around. In her review for the Boston Globe, Marjorie Adams, who had seen the shortened version, called it "the world's most extraordinary film. Nothing like it has ever been shown in Boston before, or for that matter, anywhere. The film is as exciting as the discovery of a new dimension in life."

Although incomprehensible by prevailing Hollywood standards, Kubrick's cryptic, mostly dialogue-free structure fit well with the radical avant-garde artistic innovations of the period, and the movie was an immediate countercultural hit. John Lennon quipped, "'2001'? I see it every week," and David Bowie was inspired to record his hit single Space Oddity just under a year later-a clear allusion to the film. 2001 became a genuine late-'60s cultural happening and a bellwether of the decade's generational divide. With ticket sales brisk from day one, the production ended up the highest-grossing film of 1968. "As for the dwindling minority who still don't like it, that's their problem, not ours," Clarke wrote. "Stanley and I are laughing all the way to the bank."

Fifty years later, 2001: A Space Odyssey is widely recognized as ranking among the most influential movies ever made. The most respected poll of such things, conducted every decade by the British Film Institute's Sight & Sound magazine, asks the world's leading directors and critics to name the 100 greatest films of all time. The last BFI decadal survey, conducted in 2012, placed it at No. 2 among directors and No. 6 among critics. Not bad for a film that critic Pauline Kael had waited a contemptuous 10 months before dismissing as "trash masquerading as art" in the pages of Harper's.

Although the film's vision of humanity expanding throughout the solar system proved overoptimistic, its portrait of a screen-based, technology-mediated future now seems almost uncannily accurate, and it devastatingly evokes the dehumanization that can result from such communication. As for the cyclopean HAL-9000 supercomputer, often considered the most human character in 2001, it foreshadowed our anxious contemporary discussion about the potentially dystopian impact of artificial-intelligence technologies.

The film's extraordinary predictive realism was entirely premeditated, the result of Kubrick and Clarke's questing, cerebral commitment to scientific and technical accuracy. By all accounts the production was run less like a big-budget Hollywood production than an extended futurological R&D exercise. A broad slate of top aerospace and computer companies were brought on board as consultants and advisers, with such leading innovators as IBM , Bell Labs and Hewlett-Packard all playing important roles.

In the summer of 1965, Kubrick received two detailed Bell Labs reports written by A. Michael Noll (a trailblazer in the development of digital arts and 3-D animation) and information theorist John R. Pierce (who coined the term "transistor" and headed the team that built the first communications satellite). They recommended that the spacecraft systems in 2001 all feature multiple "fairly large, flat and rectangular" screens, with "no indication of the massive depth of equipment behind them." Flat screens were, of course, unknown in the '60s -- at least outside of movie theaters -- and they helped to ensure 2001's futuristic sheen. The role of the film's sentient supercomputer, originally named Athena, grew throughout the film's development, under the influence of discussions that Kubrick and Clarke held with MIT cognitive scientist and artificial intelligence pioneer Marvin Minsky and British cryptologist and mathematician I. J. Good. The computer's physical look resulted from advice provided by IBM's influential design bureau-think-tank -- the Apple Industrial Design Group of its day -- then led by industrial designer Eliot Noyes.

In July 1965, Noyes and his team provided drawings of astronauts floating within a kind of "brain room" -- a concept that Kubrick initially rejected but later recognized as having intriguing dramatic possibilities. The astronaut Dave Bowman's methodical lobotomization of the computer after it -- or rather, "he" -- had killed off the rest of the crew, conducted within the dappled red confines of the film's remarkable brain-room set, remains one of the most powerfully disturbing scenes ever committed to celluloid.

HAL stood for "Heuristic Algorithmic," a Minsky suggestion. The computer's homicidal tendencies emerged only gradually, forcing the production to remove its original IBM nameplate and to substitute another acronym -- a kind of subliminal cognate, with "HAL" being displaced from "IBM" by only one letter in each case, something that both Kubrick and Clarke strenuously denied was intentional.

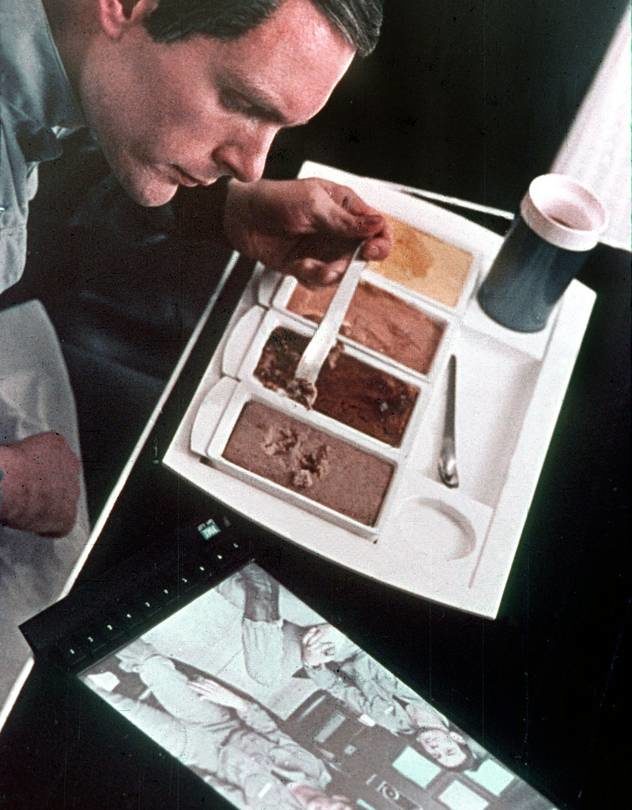

Another fascinating result of the production's consultation with Big Blue was the film's forward-looking flat-screen tablet computers, which retained their IBM logos and were called "Newspads." Constructed long before such technologies were feasible, the movie's seemingly portable Newspads were actually welded to the tables on which they appeared casually placed, with hidden 16mm film projectors recessed underneath to provide content for their frosted-glass displays.

In the film's final cut, the Newspads were only used by the astronauts to watch a TV program ostensibly from the BBC and were thus largely indistinguishable from the various other displays embedded in the sets. But the production had received permission from the New York Times to use its logo, and Kubrick's designers had mocked up a digital front page for the Newspads, complete with multiple story choices to be accessed by touch-screen command. If the page had been used, the movie would almost certainly now be seen as having predicted the internet.

More than four decades later, however, the predictive futurism of 2001 was decisively ratified when Apple released its first iPad in 2010. Samsung issued a similar device a year later, and Apple immediately sued for patent infringement. That August the Korean company filed a response in federal court in San Jose, Calif., asserting that Apple couldn't possibly have invented the iPad because the device had already been envisioned in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Samsung's unusual defense, which featured both stills and YouTube links from the film, was ultimately ruled inadmissible as evidence, but it confirmed what many fans have long appreciated: the continuing relevance and still-startling prescience of Kubrick's masterpiece.

Mr. Benson is the author of Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur Clarke and the Making of a Masterpiece, which will be published on April 3 by Simon & Schuster.

Reader Comments

Interesting link with 'The Twelves' last supper with Christ and the Union Jack = 12 united Tribes of Jacob.

As we touched on recently in another article, the Union Jack is actually made up of 3 overlapping crosses: Andrew, Patrick, and George. That makes 12 points total in Union Jack - not the 8 most laymen misquote.

Kubrick's films are full this kind of pattern obsessive weirdness, which is why they attract so many wallpaper mystics and carpet pattern weirdos, which is not to say he wasn't one himself. LOL.

Named after the River Wandle in turn stems from Anglo-Saxon 'Waendel' - possibly means white-water(?)

'Waendal' also became 'Wendal', like "Mr Wendal" by Arrested Development.

Wandsworth Prison is literally an arrested development, Lol! (ok, I'll stop now...)

Thinking back, that infant school was quite an interesting environment in that a lot of the kids there were the children of screws from the prison. They brought a bit of that stark atmosphere in with them.

I read a bit about Wandsworth Prison lately via a secondhand paperback copy of Great Train Robbery architect Bruce Reynolds' 'The Autobiography of a Thief'. There's quite a lot of insight in there about how prison system culture and the career criminal class of that time co-created each other in the yin/yang style, which I found pretty interesting.

A Clockwork Orange - Land of Hope and Glory....[Link]

Bruce Reynolds interview 'The Autobiography of a Thief'....[Link]

This particular Roman Road passes through the major energy-emitting power-points of Oxfordshire: Sandford Blake substation - largest in Oxon powering the city of Oxford; BMW Mini factory - largest industrial manufacturing unit in Oxon along with the gas-works supplying the city of Oxford; also links the cities most notorious council-estates: Blackbirdleys and Barton; before continuing through Beckley TV Radio transmition mast serving all of Oxon and East Bucks - and onto to Bicester Village, one of UK's largest retail outlets. A lot of 'B's there... maybe something to it? I call it the St Birinius Line after the founder of Dorchester Abbey and Berinsfield namesake. Interestingly Blenheim Palace and its grounds layout with its Monument aligns directly with Dorchester Abbey.

If you zoom out a bit more the Wandsworth prison map you linked, there's a little 'triskelion' building too, just to the south, maybe an Isle of Man representation... The worlds first parliament was Isle of Man I think? Isle of Man is the middle of all the British Isles linking the 'Union Jack' being within 55 miles of all the nations of Great Britain and Eire.

The Ronnie Biggs jailbreak occurred during the time I was at that school...[Link]

Much of London was like the wild west back then... If you had balls and a bit of nouse, you could get away with murder.

I think a specific set of circumstances and influences allowed for a specific type of criminality.

'Of its time', or some such.

If I ever get there, I'll try to say hello.

R.C.

* I hope that's correct, and presume it's not 'offensive' to ye SOTTites. However, if it IS 'politically INCorrect', I would request to be advised .... so that I can say it more often.

RC

Exchanging bollocks sounds a bit weird though

The Dog's Bollocks means the same as the Bee's Knees

[Link]

Q. Why does a male dog lick his testicles?

A. Because he can.

I don’t know... best to take everything with a pinch of sea salt, and bit of polysemy... yummy

Disclaimer: Spaceballs is just slap-stick humour, some sort of ex/es-oteric pattern recognition run amok for the whole film, will more than likely end in cosmic upheaval and the destruction of all life as we know it in this dimension, or your own one. Oops...

Proving that the paid shills of the previous mind control paradigm should remain as a warning to the future. I mean the guy was a complete imbecile and still here he was blathering his mouth off in an important so-called cultural news source. I mean he was so bad that one has to seriously question whether any information could possibly come from a source where it maintained an imbecile with neither vision nor talent on it's staff as a film critic of all things, whereas his obvious talent lay in scribbling daily farm reports for sow belly investors.