The study involved surveying over 2,000 DMT users, the majority of whom claimed to have had positive encounters and even emotional exchanges with beings they felt were advanced and benevolent. Most of the users, upon coming down from the drug, felt the beings were real and not manufactured solely by a hallucination.

The survey produced the following additional data: 99% had an emotional response and of those, 58% believed the entity they encountered also had an emotional response and the feeling was overwhelmingly positive, though some reported instances of fear; 81% of respondents felt the 'entities' were real; and two-thirds believed they had received "a message, task, mission, purpose, or insight from the entity encounter experience."

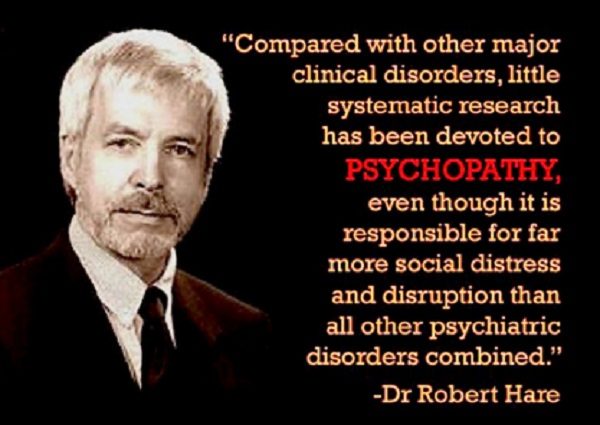

Comment: Perhaps the worst consequence of the New Age movement has been the uncritical, blind trust in one's emotional reactions. Heroin makes you feel good; that doesn't mean it is good for you. A psychopath can make you feel like a prince or princess; that doesn't mean they have your best interests at heart - just the opposite.

The study adds more anecdotal corroboration that the DMT psychedelic experience is unique from other drugs.

First discovered as a psychoactive agent by Hungarian psychopharmacologist Stephen Szara in the 1950s, DMT is a psychedelic compound of the tryptamine family. It's the only psychedelic that is found both in nature and produced naturally by the human body. Because its chemical structure strongly resemble neurotransmitters, particularly serotonin, some refer to it as 'nature's serotonin.'

As an endogenous chemical, produced naturally by the human body, it has also been referred to as the "brain's own psychedelic."

Comment: