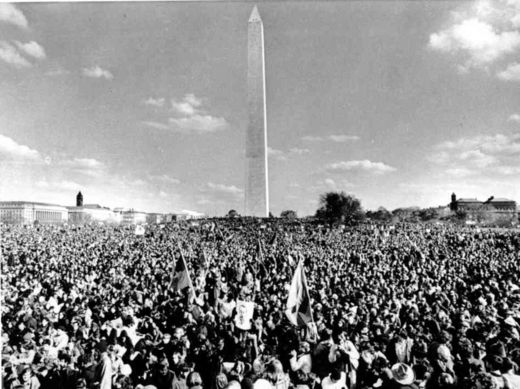

Part I - Death, Drugs and DepressionAmerican and British pop/rock music during the 60's created an art form that has been described as one of the most important cultural revolutions in history.

Within a few years, between 1968 and 1976, many of the most famous names associated with this early movement were dead. Mama Cass Elliott (earlier with the Mamas and Papas), Jimi Hendrix, Otis Redding, Brian Jones (helped form the Rolling Stones with Mick Jagger and Keith Richards), Janis Joplin were all at the Monterey Pop celebration, summer 1967.

Duane Allman Berry Oakley (helped form Allman group with Duane and Gregg Allman), Tim Buckley, Jim Croce, Richard Farina, Donald Rex Jackson (road manager for Grateful Dead) Michael Jeffery (Jimi Hendrix's personal manager), Brian Epstein (Beatles manager), Al Jackson (drummer for Wilson Pickett, back-up drummer for Otis Redding), Vinnie Taylor (Sha-Na-Na) Paul T. Williams (choreographer for the Temptations, and one of the original Temptations), Clarence White (Byrds), Robbie McIntosh (drummer Average White Band), Jim Morrison (Doors), Pamela Morrison (Jim's wife), Rod McKernan "Pig Pen" (Grateful Dead), Phil Ochs, Gram Parsons (Byrds, Flying Burritos, International Submarine Band, singing with Emmylou Harris), Sal Mineo, Meredith Hunter (victim of ritual killing at Altamont Festival), Steve Perron (lead singer of Children, wrote hit songs for ZZ TOP), and Jimmy Reed (influenced many groups, combined harmonica with guitar) were a few possible victims.

Comment: Check out our SOTT Talk Radio shows about this topic here and here.