More than 1.2 million years ago, an unknown group of human relatives may have created sharp hand axes from volcanic glass in a "stone-tool workshop" in what is now Ethiopia, a new study finds.

This discovery suggests that ancient human relatives may have regularly manufactured stone artifacts in a methodical way more than a half-million years earlier than the previous record, which dates to about 500,000 years ago in France and England.

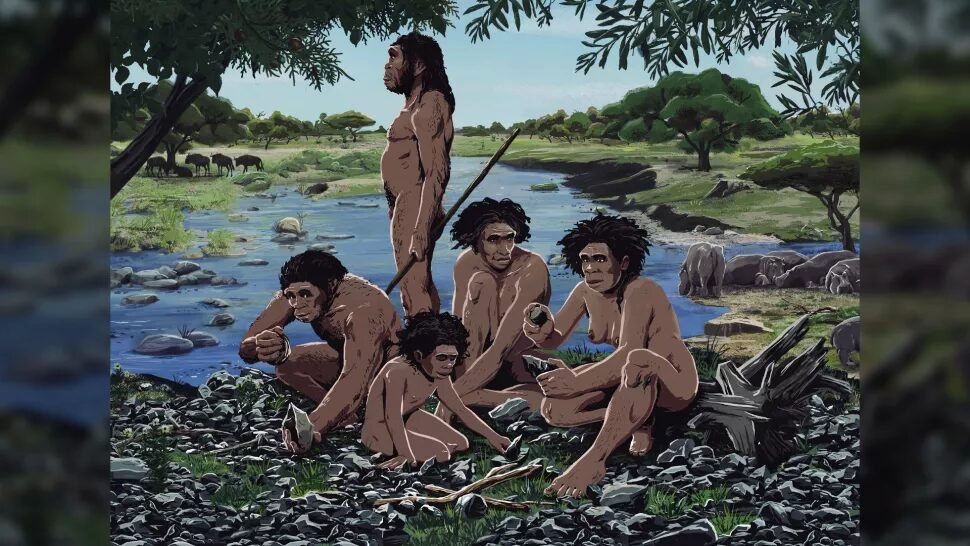

Because it requires skill and knowledge, stone tool use among early hominins, the group that includes humans and the extinct species more closely related to humans than any other animal, can offer a window into the evolution of the human mind. A key advance in stone tool creation was the emergence of so-called workshops. At these sites, archaeologists can see evidence of hominins methodically and repeatedly crafting stone artifacts.

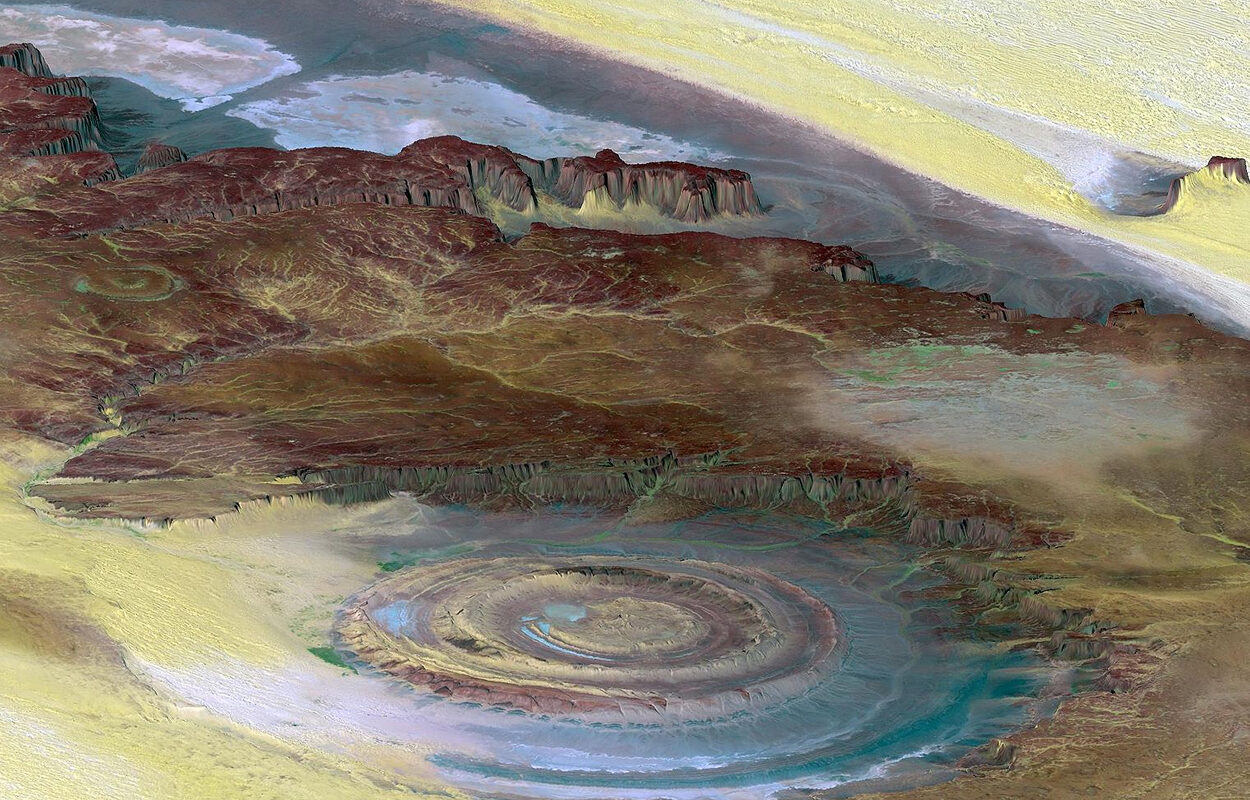

The newly analyzed trove of obsidian tools may be the oldest stone-tool workshop run by hominins on record. "This is very new in human evolution," study first author Margherita Mussi, an archaeologist at the Sapienza University of Rome and director of the Italo-Spanish archeological mission at Melka Kunture and Balchit, a World Heritage site in Ethiopia, told Live Science.

Comment: See also: Crannogs: Neolithic artificial islands in Scotland stump archeologists