Now it looks like there may potentially be a whole new type of Neolithic monument for archaeologists to scratch their heads over: crannogs.

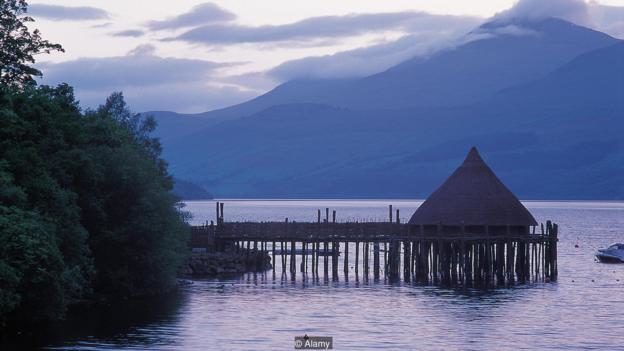

Artificial islands commonly known as crannogs dot hundreds of Scottish and Irish lakes and waterways. Until now, researchers thought most were built when people in the Iron Age (800-43 B.C.) created stone causeways and dwellings in the middle of bodies of water. But a new paper published today in the journal Antiquity suggests that at least some of Scotland's nearly 600 crannogs are much, much older-nearly three thousand years older-putting them firmly in the Neolithic era. What's more, the artifacts that help push back the date of the crannogs into the far deeper past may also point to a kind of behavior not previously suspected in this prehistoric period.

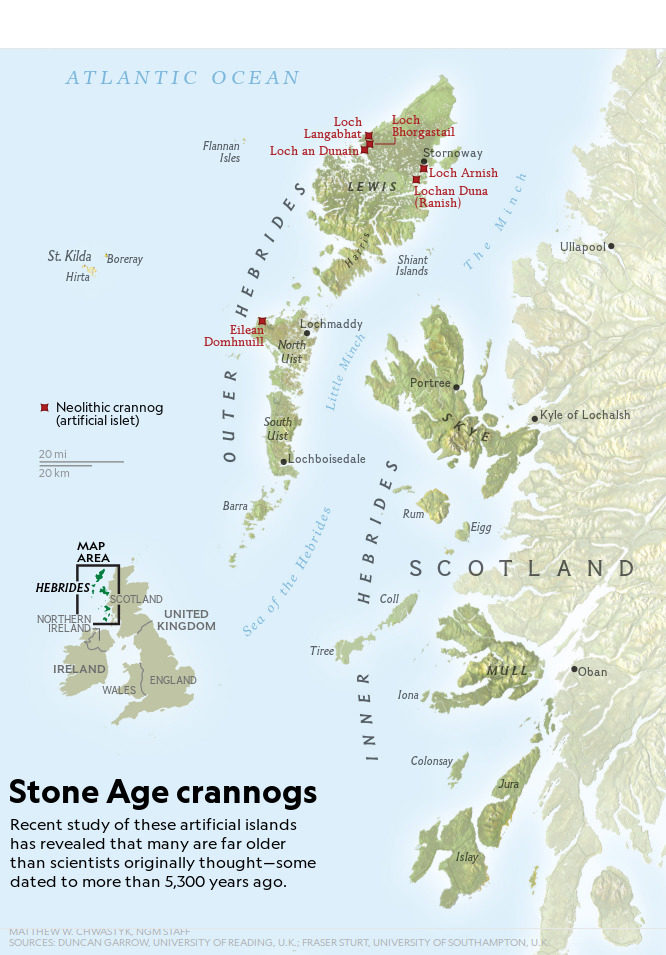

Recent study of these artificial islands has revealed that many are far older than scientists originally thought-some dated to more than 5,300 years ago.

That changed in 2012, when a local diver found distinctively Neolithic pottery in the water around crannogs in the Outer Hebrides, the windswept islands off of Scotland's western mainland. Local museum officials and archaeologists joined in the search and eventually identified five artificially constructed islets with Neolithic origins, based on radiocarbon dating of stone-age pottery and/or ancient timbers discovered near the edges of the artificial structures.

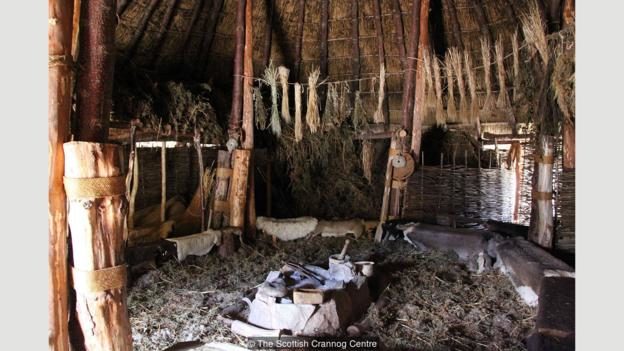

Reuse of the islets over millennia made it hard to find signs of Neolithic life on the crannogs. But the water surrounding them tells a different story. For archaeologists used to finding just bits and pieces of six millennia-year-old pottery, the condition of the nearly intact Neolithic ceramic vessels found in the water around the crannogs is "amazing," says Duncan Garrow, an associate professor of archaeology at the University of Reading, who co-authored the paper. "I've never seen anything like it in British archaeology," he says. "People seem to have been chucking this stuff in the water."

But why were Neolithic people tossing their "good china" off of artificial islets? Without direct accounts from the time period, archaeologists can only speculate as to why the crannogs were built, how they were used, and why they became places for pottery disposal.

Neolithic Britons loved building things with big rocks, but the crannogs are unlike settlements or other monuments. "Who would want to spend all of their time putting stones in a loch?" Cummings asks, pointing to the fact that some of the stones used to build crannogs weigh around 550 pounds. "It's a crazy thing to spend your time doing."

Cummings suggests the sites' isolation, and the pottery that surrounds them, could point to rituals that marked life transitions-like the passage from childhood to adulthood. "Clearly it was not appropriate to take the pottery [brought to the Neolithic crannogs] home," she says.

How many more of these "new" Neolithic monuments are out there? Only 20 percent of Scotland's nearly 600 crannogs have even been scientifically dated, and Cole Henley, a former archaeologist who specialized in Neolithic monuments and landscapes of the Outer Hebrides, warns against assuming that there are more of these sites, or that other places like Ireland may have them as well.

"Extrapolating is dangerous," he says. "It's like trying to do a jigsaw when you've only got five pieces and you've lost the box and don't know what the picture looks like."

Paper co-author Garrow admits the research is only just beginning, and his team plans to conduct a broader survey to date more crannogs in the Outer Hebrides. He hopes to use the scientific techniques that helped home in on the Neolithic crannogs-such as underwater surveys using side-scan sonar- to create even better ways of spotting new artificial stone-age islets, or prompt a reconsideration of sites already written off as Iron Age in origin. Still, it's unclear if the practice was widespread, and given the sheer volume of crannogs and the expense of surveying and archaeological diving, it's unlikely researchers will be able to date all of them any time soon.

But, says Cummings, that doesn't mean they're not out there. "Obviously we managed to miss these," she says. "[This new research] suggests that we really need to reconsider what we know."

It won't be easy. "We need to be open minded when we're looking for sites of this date," says Cummings. "They could be in any range of bizarre places." New Neolithic sites might be buried under what archaeologists always thought were Iron Age or medieval crannogs-or just hiding in plain sight in the center of a windswept Scottish loch.

Perhaps the magnetic energy would have funneled into older magnetic 'shadow' before creating a new path? Would this explain how the individuals would expend so much energy in keeping a known magnetic energy path usable? A Ley line?

We have discounted so much of our confusing history, and science continues the muddle by proposing new concepts and particles instead of looking at what is already here and used for millennia.