© Ben Behnke/ DER SPIEGELIt is known that merchants brought salt and amber through the region at the time. The trade in bronze, a new luxury material, also flourished. Küssner estimates that the "prince" and his guards kept watch over a "radius of 80 kilometers," extorted duties and fees from long-distance traders, and profited exorbitantly as a result. He believes that chieftain's gang of extortionists provided the hatchet blades in the valuable cache as a sign of their loyalty.

In 1877, when archeology was still in its infancy, art professor Friedrich Klopfleisch climbed an almost nine-meter (20-foot) mound of earth in Leubingen, a district in the eastern German state of Thuringia lying near a range of hills in eastern Germany known as the Kyffhäuser. He was there to "kettle" the hill, which entailed having workers dig a hole from the top of the burial mound into the burial chamber below.

When they finally arrived at the burial chamber, everything lay untouched: There were the remains of a man, shiny gold cloak pins, precious tools, a dagger, a pot for food or drink near the man's feet, and the skeleton of a child lying across his lap.

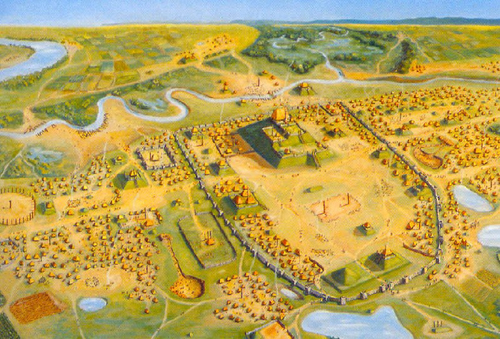

The "prince" of Leubingen was clearly a member of the elite. Farmers who had little to eat themselves had piled up at least 3,000 cubic meters (106,000 cubic feet) of earth to fashion the burial mound. They had also built a tent-shaped vault out of oak beams and covered it with a mound of stones, as if he had been a pharaoh.

For years, scholars have puzzled over the source of the prince's power. But Thuringia's state office of historical preservation has now come a step closer to solving the mystery. Agency archeologists used heavy machinery to excavate 25 hectares (62 acres) of ground in the mound's immediate surroundings, exposing a buried infrastructure. They discovered the remains of one of the largest buildings in prehistoric Germany, with 470 square meters (5,057 square feet) of floor space; a treasure trove of bronze objects; and a cemetery in which 44 farmers were buried in simple, unadorned graves.