© Flying Puffin on FlickrWoolly mammoth at Royal BC Museum in Victoria.

In 2009, a biologist named Daniel Gluesenkamp was driving through San Francisco when he

saw a ghost. Draped over a bluff by the side of the road was a twenty-foot wide shrub festooned with cream-colored flowers. Gluesenkamp immediately recognized the plant as Franciscan manzanita, or

Arctostaphylos hookeri franciscana. He was astonished, because it had been considered extinct in the wild for decades. The last known wild Franciscan manzanita had been bulldozed in a graveyard in 1947.

Before 1947, a few clippings of Franciscan manzanita had ended up in nurseries. Today you can

buy the plant online. But the nursery form is the result of hybridization and extreme breeding; it's now about as much like wild Franciscan manzanita as a German shepherd is like a wolf. It's unlikely it could survive in the wild anymore. For thousands of years, wild Franciscan manzanita had grown luxuriantly in the prairies that carpeted much of the California coast. Now the wild plants were all gone - or almost, it turned out.

Before Gluesenkamp's discovery, the U.S. government officially listed Franciscan manzanita as extinct in the wild. But then three organizations - the Wild Equity Institute, Center for Biological Diversity, and California Native Plant Society - petitioned the U.S. government to change its status. In 2012, the Fish and Wildlife Service agreed to the request and

reclassified Franciscan manzanita from extinct to endangered. Its known wild population was precisely one.

This wasn't exactly the original plan for the Endangered Species Act when it was enacted in 1973. It was intended to protect species that were moving in the other direction, from healthy populations towards extinction. But once the single wild Franciscan manzanita plant came to light, the government decided that it deserved protection, too.

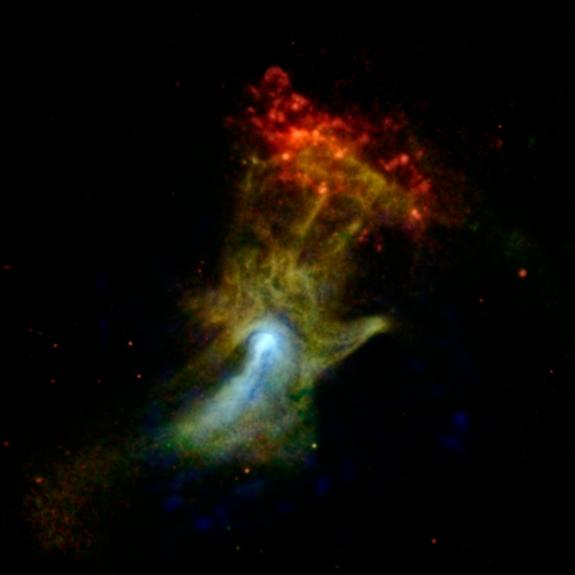

Comment: The 'new research' they need is already available in the Thunderbolts Project's Electric Sky and Electric Universe.

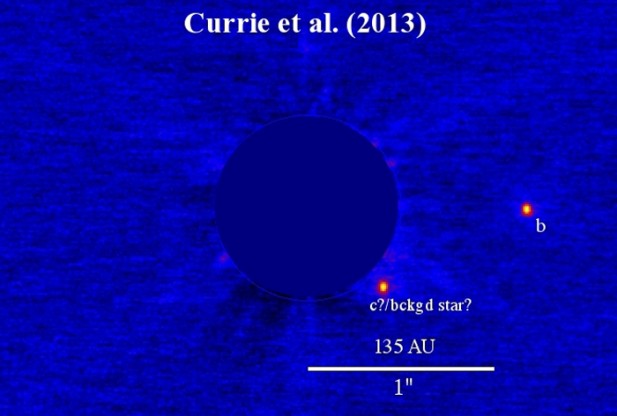

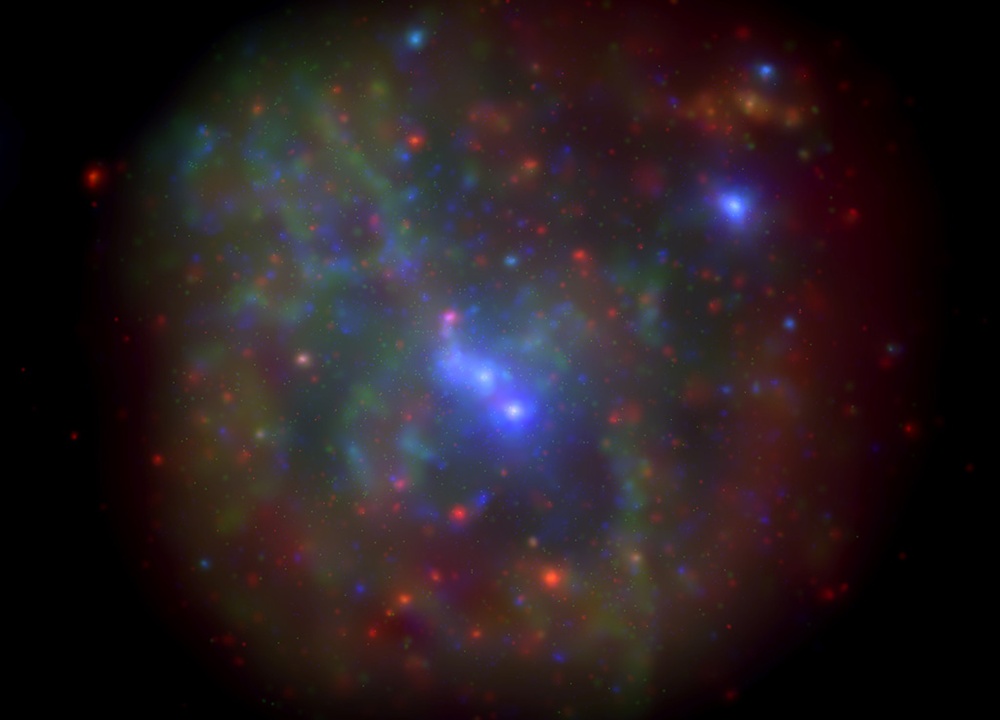

According to conventional astronomical theory, brown dwarfs are small stars nearing the end of their life because their 'internal Fermi reactions' are decreasing due to lack of fuel (hydrogen), making them progressively dimmer and dimmer. However, there are several problems with this model. For starters, brown dwarfs emit X-rays: So, in standard astronomical models, brown dwarfs are 'supposed to be' too cool and too small to maintain fusion reactions in their cores. The minimum temperature 'should be' three million degrees kelvin and the mass should be at least seven percent of the Sun's mass, but some previously classified 'brown dwarfs' have actually not met those requirements, and, as a result, are too small to generate a gravitational collapse to trigger nuclear fusion and subsequent X-ray radiation.

But a brown dwarf presents no such anomaly in electric models. It's simply a star that is not glowing because the local electric field is too weak. From this perspective it's not the size (and therefore the limited gravitational field) that makes a star dark, but the electric stress. If the electric stress is too low, the star (whatever its size) doesn't glow. Thus the maximum size determined by mainstream science to define brown dwarfs is irrelevant.