Scientists have analysed the oldest charred food remains ever found, providing the earliest evidence of plant cooking among Neanderthals.

Ancient hunter-gatherers were thought to have a largely meat-based diet, but researchers have found that prehistoric people had a diverse diet in which plants featured heavily.

Comment: What exactly does 'featured heavily' mean? That they ate a large quantity of them? Or there was a large selection and they featured often? Because having a salad or a piece of bread with a steak doesn't count as 'featuring heavily'.

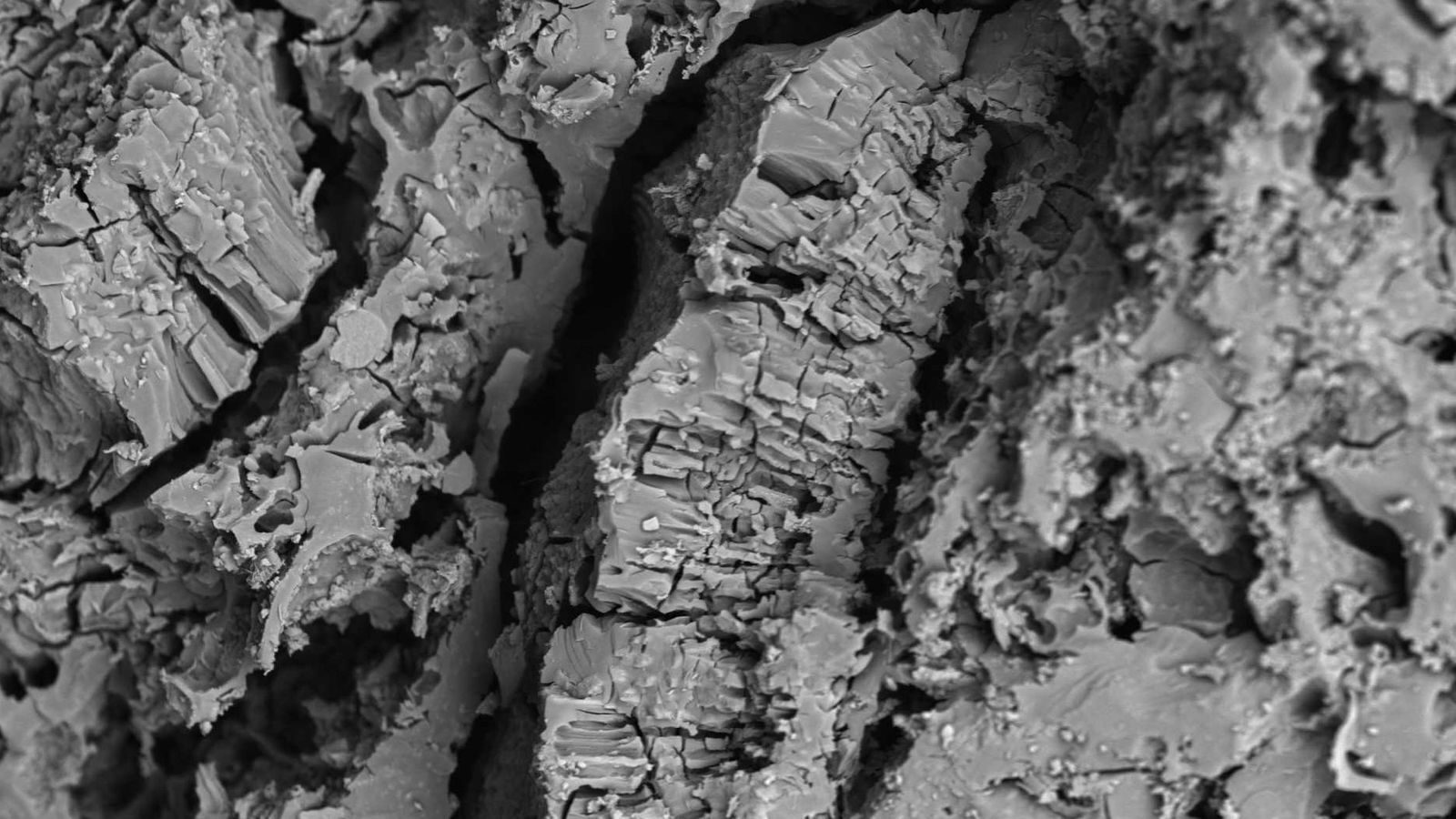

Researchers used a scanning electron microscope to analyse nine samples of ancient charred food from two sites: Shanidar Cave, a Neanderthal and early modern human dwelling around 500 miles north of Baghdad in Iraq, and Franchthi Cave in Greece.

Five food fragments recovered from Shanidar are the "earliest" of their kind found in southwest Asia, dating back 40,000 and 70,000 years, according to Ceren Kabukcu, a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Liverpool, who led the study published in the journal Antiquity.

The carbonised pieces of prepared plant foods include a mixture of different seeds, wild pulses, wild mustard, wild nuts and wild grasses - which could have formed the Neanderthal diet.

"They look like charred crumbs or fragments of what could be patties, thick porridge", Dr Kabukcu told Sky News.

The four remnants recovered from Franchthi are the earliest of their kind recovered in Europe, from a hunter-gatherer occupation around 13,000 to 12,000 years ago, she added.

Comment: The timescales mentioned above are rather large and featured significant changes to prehistoric human life during that time, including the extinction of the Neanderthals and the subsequent extinction of the megafauna at the Younger Dryas Boundary.

One of the food deposits was found to be "bread-like".

Cooking tricks

The team were also able to identify the cooking tricks used by Neanderthal and early modern human chefs to make food taste better.

Pulses, the most common ingredient identified, have a naturally bitter taste, which chefs from the Stone Age quelled by soaking, leaching and then pounding or grinding them.

Pounding or grinding the food would also make it easier for the body to absorb the nutrients, as well as provide more cooking options.

The bread-like meal found in Franchthi Cave was made by grinding seeds into super-fine flour, according to the researchers, showing that hunter-gatherers developed specialised cooking practices in the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic period, tens of thousands of years ago.

Comment: That would make sense since evidence suggests that Australian Aboriginal people were farming grain and baking bread from at least 30,000 years ago.

"Our work conclusively demonstrates the deep antiquity of plant foods involving more than one ingredient and processed with multiple preparation steps," said Dr Kabukcu.

In modern agriculture the bitter compounds are almost entirely eliminated, but neither the Neanderthals nor early modern human chefs were found to remove the entire seed coat, keeping some pulses' natural bitter taste in their meals.

The findings suggest that "plants with strong flavours, some bitter, some sharp, some rich in tannins were important ingredients (or seasoning) of Palaeolithic hunter-gatherer cooking," Dr Kabukcu told Sky News, adding that "there were very ancient and sophisticated culinary traditions resting on these plant flavours" from a very early period.

Comment: It does seem as though at least some of these remnants, with their 'strong flavours', such as mustard seed, could indeed be seasonings, as well as perhaps 'side dishes'. It may also be that, at times, these peoples chose, either through necessity or preference, to also eat some plant foods.

However, note that data derived from Neanderthal and hunter gatherer teeth and bones - as well as other kinds of data, such as evidence of butchery sites - show that meat of various kinds (including aquatic mammal and fish) seems to have constituted the bulk of their meals: Isotopes found in Neanderthal bones suggest they were meat eaters