The team said the discovery not only underscored the horror of the antisemitic atrocity, but provided new insights into when genetic disorders often found among Ashkenazi Jews first appeared.

"I'm really excited that 12 years on [from our first investigations], we've finally been able to use historical records, archaeology and ancient DNA analyses to shed new light on a historical crime, and in doing so sequenced the oldest genomes from a Jewish population," said Dr Selina Brace, lead author of the research from the Natural History Museum in London.

The remains of at least 17 individuals were discovered in Norwich in 2004 during construction at a site intended for a shopping centre.

With no sign of trauma on the bones, it was possible the remains were of victims of famine or disease. But analysis of the bones and associated pottery more than a decade ago, which suggested they were dumped in the 12th or 13th centuries, ruled this out.

As a result, the research team suspected the bodies may have been victims of violence.

"We don't know actually how they were murdered, but it seems most likely that they were," said Brace, adding that it appears the bodies were deposited at the same time, with many thrown headfirst.

Now Brace and her colleagues say they have finally cracked the medieval mystery.

Writing in the journal Current Biology, the team say that further radiocarbon dating analyses have revealed the bodies were deposited in the well between AD1161 and AD1216.

The team say the timeframe is consistent with an antisemitic massacre in Norwich in AD1190, detailed by the chronicler Ralph de Diceto.

"Many of those who were hastening to Jerusalem determined first to rise against the Jews before they invaded the Saracens. Accordingly on 6 February [in AD1190] all the Jews who were found in their own houses at Norwich were butchered; some had taken refuge in the castle," he wrote in his Imagines Historiarum II.

But there were other violent events in the same period, including the sack of Norwich by Hugh Bigod in AD1174.

To delve deeper the team turned to genetics.

The researchers' previous DNA work, conducted for a TV programme, hinted the individuals may have been Jewish and hence killed in the pogrom, but the work had only involved short pieces of genetic material and results were not conclusive.

Now, using recent advances in DNA analysis, the team were able to piece together whole genomes for six individuals.

"When we look at the DNA from [the remains], they're actually more closely associated to modern day Ashkenazi Jews than to any other modern population," said Brace, noting that - with Jewish law largely prohibiting the exhumation or disturbance of burials - the genomes are the oldest yet sequenced from Jewish individuals.

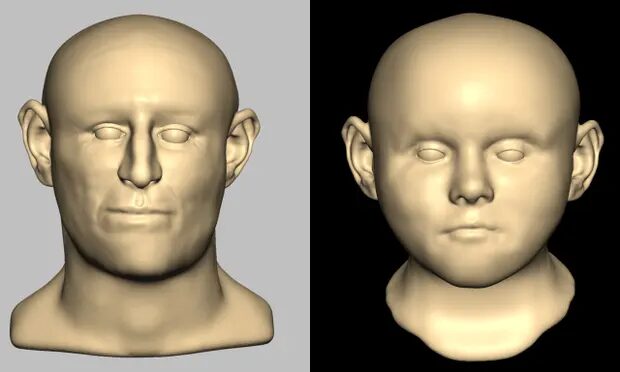

The team discovered that three of the victims were sisters - one a young adult, one aged between 10 and 15, and one aged between five and 10 with brown eyes and dark hair.

Another was a young red-headed boy with blue eyes - a significant finding given that such hair colour was associated with European Jews at the time. The other two individuals were a juvenile and an adult male.

The team also found genetic variants associated with diseases often seen in modern day Ashkenazi Jewish populations, such as a predisposition to certain cancers and delayed puberty.

But the frequency of such variants was far higher than expected. "It's what you would expect to see if those diseases were as common then as they are today," said Brace.

As genetic disorders usually become more common when a population shrinks in size, it appears Ashkenazi Jews experienced a "bottleneck" before the 12th century - hundreds of years earlier than previously thought.

The team says the low frequency of the same genetic variants in the Sephardi Jewish community suggests this bottleneck most likely occurred when the Jewish diaspora split during the early medieval period, rather than in a later event as previously thought.

Brace added that the remains were buried some years ago. "They've been given a Jewish ceremony," she said.

They were converts in the 7th century from the land of Khazaria.

The Diaspora? Very misleading.