In September, neurosurgeon Michael Egnor debated atheist broadcaster Matt Dillahunty at Theology Unleashed, on the existence of God. This time out (October 22, 2021), he is teamed with distinguished South African neuropsychologist Mark Solms, author of The Hidden Spring (2021) — who begins by declaring, in his opening statement, "the source of consciousness in the brain is in fact in the brain stem," not the cerebral cortex, as almost universally assumed. He explains his reasoning with evidence.

Egnor doesn't dispute that statement; in fact, in his own opening statement later, he reinforces it with observations from his own practice. To learn more, read on.

A partial transcript, notes, and links to date follow the video link:

Arjuna [host]: Hello, and welcome to Theology Unleashed. I'm Arjuna and this is the channel where Eastern theology meets Western skepticism. Today, I've got two neuroscientists on and we'll be discussing... Let me find it. Yeah. We'll be discussing consciousness and the brain... And we'll get started by having our guests describe their views. So, Mark, could you please explain your views on the brain and consciousness, and physicalism? [00:02:30]

Mark Solms: I have been led to the view, over a few decades of working in this field, that we've made a big mistake in our conception of consciousness in neuroscience. The mistake has a very long history, which I won't go into, but it boils down to the view that the seat of consciousness in the brain is the cerebral cortex. This is an absolutely universal view with a very few... few exceptions, myself included, obviously.[00:03:30]

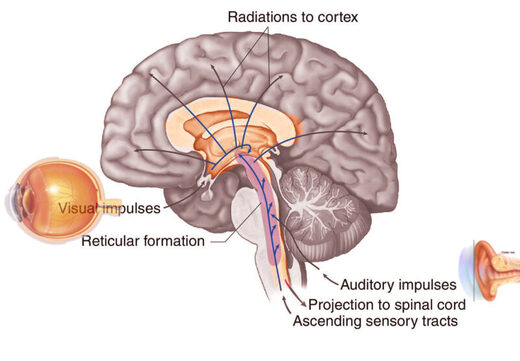

It's our evolutionary pride and joy. But ... a lot of evidence, suggests that the source of consciousness in the brain is in fact in the brain stem, which is a much more ancient, much more primitive structure that we share, not only with all other primates and all other mammals, but in fact, with all vertebrates. The basic structure of the brain stem in you and me is the same as it is in fishes. If you're going to look at it from the physical point of view, which part of the brain, is bound up with this mental property that we call consciousness? It is the reticular activating system, in particular, of the brain stem. It's primitive core. I said, there's tons of evidence, but let me just mention the most dramatic bit of evidence. [00:05:00]

If something frightening happens, they are frightened. And they show feelings of fright and irritation, if something frustrating happens. Or joy and laughter if something happy happens. So, there you have it, in a nutshell. These kids are conscious. There is something that is like to be them, that they have qualitative experience, there's a content to their minds, and yet they have no cortex at all. So, that is the most dramatic evidence for the view that I've come to.

It's not by any means the only line of evidence. And with such a complex question, you wouldn't want to rely on only one method. But that, as I said, is the old fashioned basic ABC method in behavioral neuroscience. There's something dramatically wrong with our idea that cortex is the seat of consciousness. So, that's my starting point for our conversation tonight, as far as the brain and consciousness is concerned. [inaudible 00:07:11]

Arjuna: Do you think the brain is completely responsible for consciousness? Whether the brain stem or the whole thing as an entirety. Or is there some aspect of consciousness which is perhaps fundamental, or maybe you're agnostic, to whether there's a soul or something? [00:07:30]

Mark Solms: Unfortunately, here too, I find myself at odds with my colleagues. And it gives me no pleasure to be at odds with my colleagues, because it's lonely and you want to be liked and you want everyone to say, "Yep, we're all on the same side. We agree." But unfortunately, I hold a different view on that score too. I am not a physicalist in the sense of, I do not believe that the mind can be reduced to material processes.

My position... is what is commonly called dual-aspect monism, associated above all others with the name of Baruch Spinoza. And that view is that, to put it in its simplest terms, when I wake up in the morning with my eyes closed, and I feel myself to exist with gratitude, thank heavens, here I am. I'm Mark Solms. I'm alive. That's my mind. When I then stagger over to the bathroom, and look at the mirror and see this body, I see, oh, there's Mark Solms, he's alive. And it's equally reassuring, but I don't believe that that's something else. [00:09:00]

Mark Solms: I believe it's the same thing as I experienced myself to be. I don't think there are two Marks Solms as I think they're one. And now, we have this problem. How come I have this experience called my mind, of being Mark Solms, and then I have this objective physical thing called my body, which is also Mark Solms. And how can they be one in the same thing? The dual-aspect monist philosophy is simply that they're two different appearances, two different ways in which we can observe a single entity. The question then arises, well, then what is that single entity? [00:09:30]

Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677)

And this is the point of difference with my colleagues. I don't think that the single entity is actually just my body, and that my mind is somehow a function of it. I think that the single entity underlies both of them. That there's something behind or beyond the appearance of the body and the mind, which unifies them. And that's my position.Note:Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677) "is one of the most important philosophers — and certainly the most radical — of the early modern period... His extremely naturalistic views on God, the world, the human being and knowledge serve to ground a moral philosophy centered on the control of the passions leading to virtue and happiness... Of all the philosophers of the seventeenth century, Spinoza is among the most relevant today." - Internet Encyclopaedia of Philosophy

I take all the data from subjective experience, which is what psychology is all about. And I take all the data from physiology and anatomy, which is what neuroscience is all about. And I see these as two different points of entry, two different sets of evidence about how this underlying thing works. This thing, which we have to infer the functional organization of this underlying entity, which you might call the apparatus of the mind, or the instrument of the mind, or the functional system of the mind. [00:10:30]

A good analogy is lightning and thunder. You see with your eyes, a flash of lightning, as you hear with your ears, a clap of thunder. It's a stupid question to say, "How did the lightning cause the thunder?" The one doesn't cause the other, they're just two different ways of registering one in the same thing. So, that is my position. And I need to add one further wrinkle to this, because I'm aware that I'm talking to Michael Egnor. And that is, when it comes to what is the nature, the true nature, of this underlying entity which appears to us in these two different ways, I think that we have to have a bit humility, that we have to recognize that there's some things that you can't know directly, you can't experience directly. [00:12:00]

You have to recognize the limits of your capacity to know things. And I think we need a bit more of a sense of mystery and science, and humility. So, the true nature of the essence of the person or any other conscious creature for that matter, I think, is something we can only make guesses about. The scientific method allows us to make a systematic approach to trying to make better guesses than we made a hundred years before. But there are nevertheless, always going to be guesses. The closing sentence, I think, of Stephen Hawking's famous book, A Brief History of Time, is something about, eventually we're going to have a theory of everything, and then we will see the face of God. And my view is, that ain't going to happen. We're never going to see the face of God. [00:12:30]

Next: Michael Egnor, based on clinical experience, agrees with Solms on frontal lobes: "I saw very much the same things that Mark wrote about in his book. I saw patients who didn't have frontal lobes, or at least most of their frontal lobes, who were completely conscious, in fact, rather pleasant, bright people." (upcoming segment)

Comment: See also: