The tornado descended Sunday afternoon, causing minor damage as it passed along the northern periphery of the airport and into nearby neighborhoods. El Alto International Airport is the highest international airport in the world at 13,313 feet, serving the city of La Paz.

The whirlwind reportedly came without warning from El Servicio Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología, Bolivia's equivalent to the National Weather Service. The main weather hazard highlighted before the tornado had been river flooding well to the east amid recent heavy rainfall.

Eyewitness video shows the twister's condensation funnel looming ominously overhead as its rotating winds churned closer to the airport. Additional footage shows the tornado lofting debris, evidence that the circulating winds snaked all the way down to ground level.

At an altitude of at least 13,200 feet, this tornado could be a contender for one of the highest-altitude tornadoes recorded worldwide. Limited data exists on such tornadoes globally, so there's no way to comprehensively confirm the El Alto tornado's standing. But at least in the United States, no tornado has been noted above 12,200 feet.

In 2012, a slender landspout tornado touched down on the side of Mount Evans in Colorado at 11,900 feet. Eight years earlier in 2004, a picturesque twister dropped from a supercell thunderstorm near the Rockwell Pass area of Sequoia National Park in California. The National Weather Service office in the San Joaquin Valley confirmed that the tornado made contact with the ground at an altitude of 12,156 feet.

But El Alto — a name that literally means "the high" — witnessed a tornado more than 1,000 feet higher. A quick search revealed no other tornadoes globally at such lofty altitudes. Spinning up this particular tornado required an unusual set of circumstances.

What may have caused the El Alto tornado?

The climate of Bolivia is influenced by its topography. The Andes Mountains cut northwest to southeast across the country. Atlantic moisture pools to the east, allowing fringes of the Amazon rainforest to spill into the northeastern part of the country.

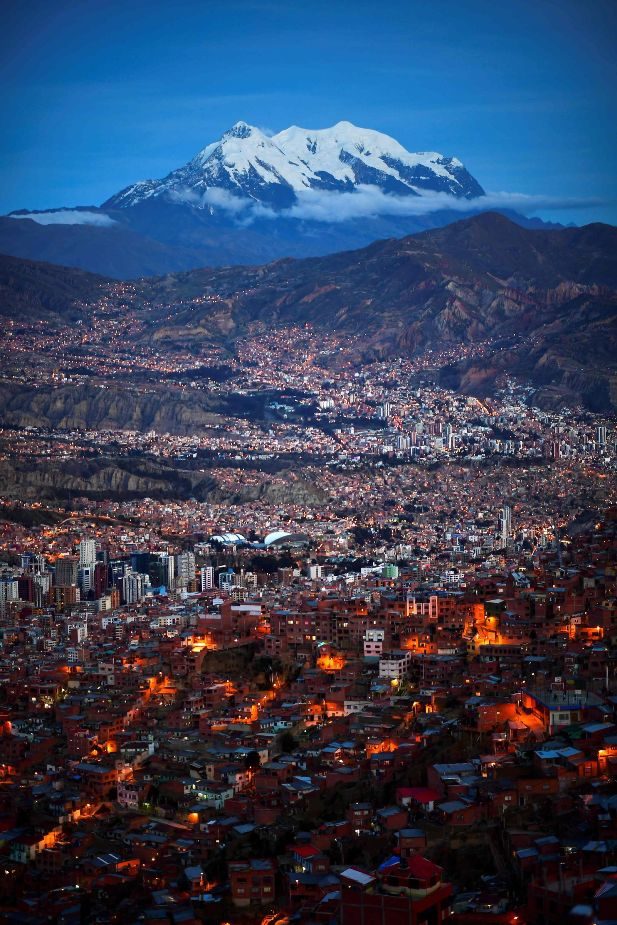

La Paz is the administrative capital of Bolivia and is home to 800,000 people. It sits at about 11,900 feet. A system of chairlifts and gondolas are strung throughout the city's mountain terrain, serving as one of the primary means of public transportation. To the east, the Andes Mountains tower to 18,000 feet or more.

But just to the west is El Alto, an extension of La Paz with about 600,000 people. That's where the airport is. It's a steep drive up from La Paz, but is situated on the "Altiplano" — a vast stretch of mostly flat land about 100 miles west to east and 500 miles north-south between the mountains. They're basically plains, but at 12,000 or 13,000 feet. Lake Titicaca is in the Altiplano.

Even though the Altiplano is high in altitude, it still heats up beneath intense sunlight (similar to the Plateau of Tibet in the summertime). That favors rising air motion. Summer evenings over the Altiplano can feature large thunderstorm complexes west of the mountains.

Getting thunderstorms is one thing. Getting one to produce a tornado is different, however.

A look at past data suggests a very subtle trough of low pressure was in the process of developing over central Chile and western Argentina late Saturday into early Sunday. However, Bolivia was well removed from any jet stream energy, and large-scale temperatures in the mid to upper atmosphere were not overly conducive to severe weather. That suggests whatever happened came together on a local level.

At first glance, it does not appear this was a supercell thunderstorm, which is a thunderstorm that contains a long-lived, rotating updraft.

That's based on the aforementioned factors, plus the tornado's apparent counterclockwise spin. Nearly all supercell-spawned tornadoes in the Southern Hemisphere spin clockwise.

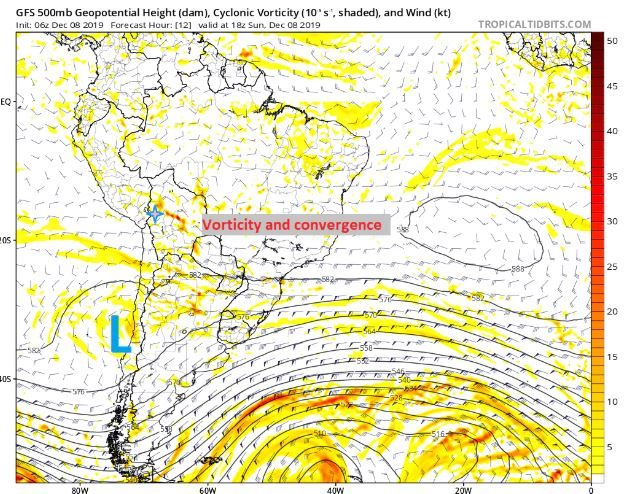

Instead, it looks like the trough of low pressure to the southwest may have helped enhance westerly winds over the Altiplano, while more northwesterly winds were present just to the east. A ribbon of low-level convergence, or colliding winds, may have helped set up a localized boundary that could focus storm development. Models also captured this feature sparking some vorticity, or spin, at the mid-levels of the atmosphere. See the small strip of red modeled to be near La Paz (in a blue/pink star) Sunday:

This could have helped thunderstorms rotate on a local level.

It appears storms were moving to the southeast; depending on the exact vector, a column of air moving from the higher terrain just north of El Alto could be vertically stretched as the terrain dropped off slightly in the vicinity of the airport. That would have tightened/strengthened rotation.

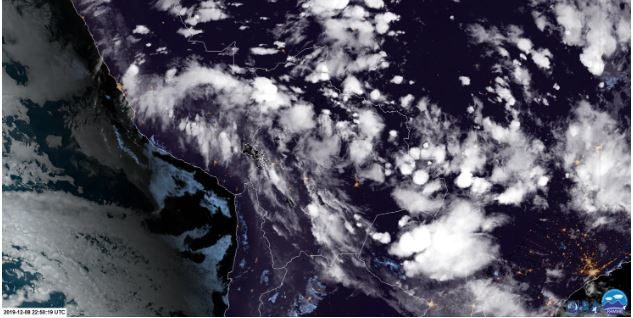

And lastly, satellite imagery from just after sunset Sunday night show a discernible, broad rotation over central/western Bolivia. Notice the clockwise flow evident in the pattern that the thunderstorm anvils make. There may have been a sneaky surface low trying to develop over the eastern Altiplano, enhancing low-level helicty (rotation). That wasn't really captured in the models, but satellite observations suggest it.

Whatever the case, Sunday's tornado in Bolivia beat out any confirmed tornadoes in the United States for altitude. It's an extraordinary example that shows unusual weather can, and occasionally does, happen anywhere.

Comment: Some other rare, unseasonal and very large tornadoes to have formed around the planet this year include:

- Second freak tornado to touch down in France this week

- North Texas tornado outbreak caused $2 billion in losses, the costliest in state history

- Climate chaos! Tornado tears through Luxembourg - Another touches down in Amsterdam

- Rare tornado strikes China's Kaiyuan City, killing 6 people and injuring at least 190

- Freak winter tornado with 200km/h winds flattens home in Victoria, Australia

- Extremely rare, large tornado hits southern Taiwan

- Rare clockwise-rotating tornado touches down in South Dakota

- Large, extremely rare tornado hits central Chile

- Tornado that obliterated Linwood, Kansas, was mile-wide EF4 twister with top winds of 170 mph

- Rare twin tornadoes snapped in the Scottish highlands

- Monster tornado that ripped 20-mile trail of destruction through Missouri capital was almost a mile wide

- Epic tornado in Romania lifts bus into the air

Mainstream science does not consider the importance of atmospheric dust loading and the winning Electric Universe model in their research.Such information and much more, are explained in the book Earth Changes and the Human Cosmic Connection by Pierre Lescaudron and Laura Knight-Jadczyk. See also: Thunderbolts Space News: Tornadoes - The Electric Model