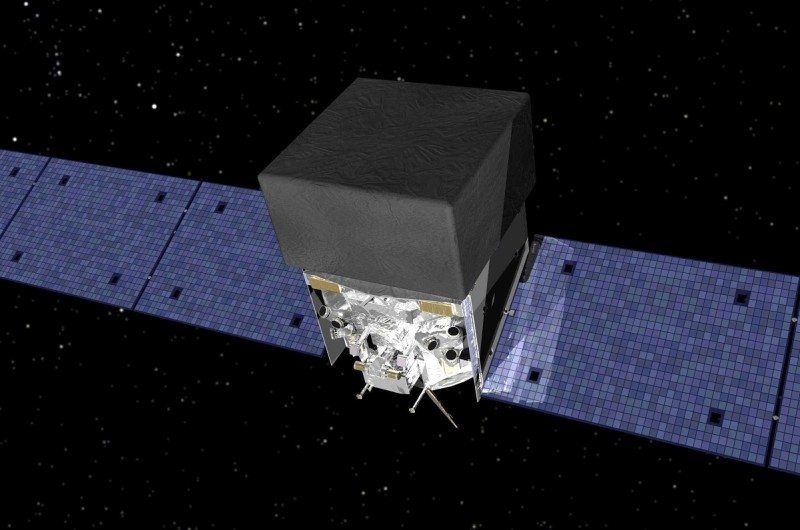

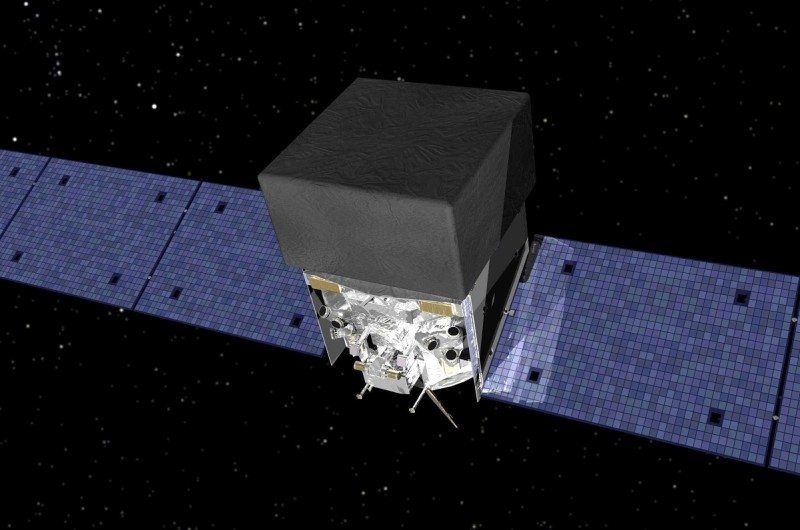

© NASAThe Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope

There's something wrong with the sunshine. A nine-year survey of the sun's gamma rays has turned up two surprises:

an unexpected dip in low-energy gamma rays, and far more high-energy gamma rays than theory predicts. And we're not sure what's going on.

"The sun is much weirder than we thought," says

John Beacom at Ohio State University in Columbus. He and his colleagues examined data from the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope taken from 2008 to 2017.

Gamma rays are constantly being produced in the sun as high-energy protons from cosmic rays smash into gas particles in the solar atmosphere. The sun's magnetic field directs the paths of these protons, flinging some of the resulting gamma rays towards Earth where we can detect them.

Overall, Beacom and his colleagues saw gamma rays with energies ranging from about 1 gigaelectronvolt (GeV) to about 200 GeV. But between 32 and 56 GeV, there was an abrupt dip - there were only about half as many gamma rays at those energies than the average over all energies.

"It seems inexplicable, random and strange," says team member

Kenny Ng at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel. "In terms of energy scale, there is nothing special about 30-50 GeV."

Possible problemsThe researchers came up with several potential explanations, but none of them seems quite right, they say.

They suggest that the sun's magnetic field could potentially focus the higher-energy radiation by collecting cosmic rays from every direction and only re-emitting gamma rays in the direction it's rotating. But no other observations indicate that sort of solar magnetic field geometry. As for the lower energy gamma rays, the authors say some may be absorbed by

gas within the sun, but admit that the gamma rays would interact with that gas so rarely that it seems unlikely.

Or, it might just be a problem with the telescope itself. The detector is shielded from charged particles to avoid contaminating the data, but neutrons that the sun also emits - which are chargeless just like gamma rays - could be sneaking through and messing with the analysis.

High-energy mysteryIf the dip were simply at the end of the spectrum it wouldn't be so strange - plenty of astronomical phenomena have maximum energies above which they drop off.

But the fact that the gamma rays come back above 50 GeV, and that there are even more of them at high energies than at low ones, is unexpected."The higher the energy of the gamma ray, the harder it is to make it," says Beacom. "But the process of converting cosmic rays into gamma rays seems to be more efficient at higher energies, not less. It makes no sense."

Segev BenZvi at the University of Rochester in New York says that other experiments are now trying to match these observations to see if the strange features persist. "The study of this gamma ray excess will lead us to new understandings of the structures of the magnetic field of the sun, and I have no idea what those are going to be," he says. "It'll be really interesting to see how much of this gets repeated in the next few years."

Reader Comments

Typical clueless mainstream science that cannot see the forest for the trees. Or more likely, hiding the fact that we are entering another ice age of undetermined duration.

By, bye Age of Deception. You are headed for the deep freeze and a close encounter of the cometary kind.

From my brief schooling, the sun has been around for quite a few millions of years, quite probably billions. We have only been around for an effective million or two. Yet, we believe we are entitled to criticize the sun, for our mistakes, misunderstandings, misinterpretations, missing everything.

Keeping it short - To maintain a healthy bit of sanity, please, I suggest you closely follow the two simple steps which follow.

Allow your marijuana to mature, a bit at least.

Allow your marijuana to dry properly,

before attempting to smoke same.

Please, I insist.

Shalom

No, I won't put the link here for that song, LOL!!

Natural, cyclical weakening of the Sun is too small to observe by senses, so I suppose it's the dust in atmosphere, or change in the spectrum. Well, or change in my senses, like smaller pupil... But I use mostly the same monitor as almost 10 years ago, and don't have to ramp up brightness (so it's probably even less than it was, due to wear of backlight lamps).

Why does John think the sun is weird? What kind of scientist is John, anyhow?

What is weird is these perpetual unprincipled expectations turning up unverified. Poor theorists, analysts, and-- well, you know the routine.

I'm not saying that he's as right as he believed he was, but he makes a hell of a lot of eye opening points that 'science' prefers to ignore.

{ Same with Stichin. (sp)]

R.C.