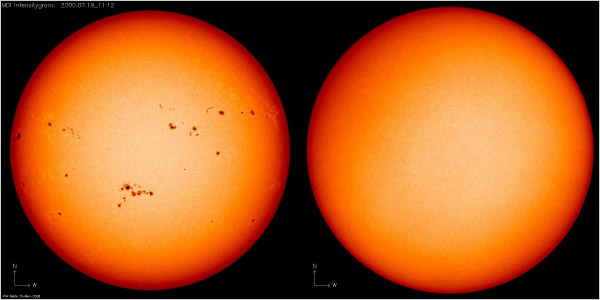

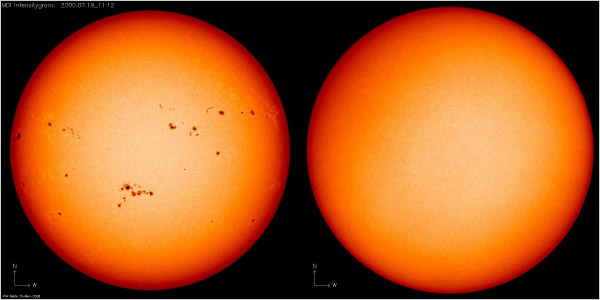

© NASASUN GAZING These photos show sunspots near solar maximum on July 19, 2000, and near solar minimum on March 18, 2009. Some global warming skeptics speculate that the Sun may be on the verge of an extended slumber.

Ever since Samuel Heinrich Schwabe, a German astronomer, first noted in 1843 that sunspots burgeon and wane over a roughly 11-year cycle, scientists have carefully watched the Sun's activity. In the latest lull, the Sun should have reached its calmest, least pockmarked state last fall.

Indeed,

last year marked the blankest year of the Sun in the last half-century - 266 days with not a single sunspot visible from Earth. Then, in the first four months of 2009, the Sun became even more blank, the pace of sunspots slowing more.

"It's been as dead as a doornail," David Hathaway, a solar physicist at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala., said a couple of months ago.

The Sun perked up in June and July, with a sizeable clump of 20 sunspots earlier this month.

Now it is blank again, consistent with expectations that this solar cycle will be smaller and calmer, and the maximum of activity, expected to arrive in May 2013 will not be all that maximum.