The courts, in the exercise of what is called "equity jurisdiction," have long excused borrowers from obligations incurred through fraud, duress, and other forms of creditor unfairness.

In addition, federal bankruptcy laws (authorized in the Constitution by Article I, Section 8, Clause 4) offer a path to safety for debtors who get in over their heads.

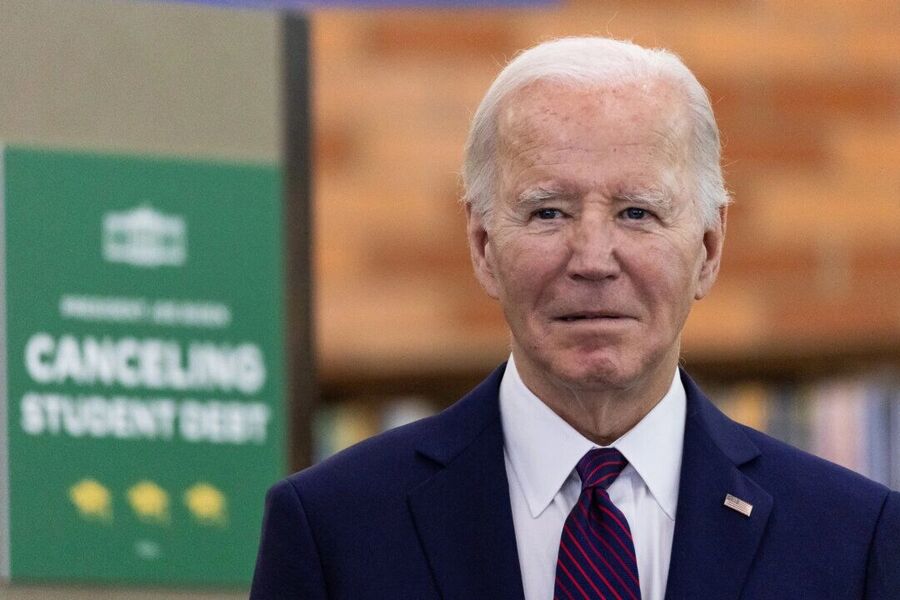

President Joe Biden's "student loan forgiveness" measures qualify as neither. Instead, they are classic examples of what James Madison called an "improper or wicked project."

Under the president's program, no debtor will have to declare bankruptcy. And far from being victims, they already have enjoyed the benefit of very favorable loan terms at taxpayer expense. The borrowers spent the money for what both they and the federal government thought was a good purpose.

Still, you and I will have to pay their bills.

Madison called debt cancellation "improper or wicked" for very good reasons. Cancellation does not abolish an obligation. It merely transfers it to innocent people. If you are reading this, chances are that you will be one of those victimized by the Biden program.

Cancellation also injures the capital markets. In other words, it makes creditors less likely to lend on favorable terms. This makes it harder for deserving people to borrow.

Cancellation damages the sense of personal responsibility. It frays the social fabric by creating bitterness between different classes of people.

Nevertheless, for centuries demagogues have used debt-cancellation to buy votes. They then find ways to exploit the resulting bitterness for political advantage.

America's Experience

The American Founders had learned all about debt cancellation from their study of history. But they also learned about it from personal experience.

During the 1780s, the newly independent United States fell into economic recession. Some debtors got behind in their payments. Many were determined to pay, but others wanted to dodge their obligations.

The dodgers put pressure on their state legislatures. Some of the legislatures yielded to the pressure.

In some states, lawmakers issued fast-depreciating paper money, and forced creditors to accept it in lieu of other forms of payment. In other states, they granted debtors lengthy extensions. (Laws authorizing these extensions were called "stay laws" or "installment laws.") Still other state legislatures allowed borrowers to discharge debt by offering creditors cheap or worthless property ("tender laws" or "pine barren laws").

These measures were part of a wider pattern by which states adopted statutes with retroactive effect.

The Disastrous Results

The 1780s state "debtor-relief" measures proved disastrous. The American economy got worse. Creditors stopped lending. Bitterness grew between different classes of people.

Bitterness also grew among the states. For example, many people in Connecticut had loaned money to Rhode Islanders. When the Rhode Island legislature adopted laws excusing its citizens from paying Connecticut creditors, the Connecticut legislature retaliated with new laws of its own.

Soon the two states were on a path toward war.

Fortunately, leading American statesmen understood that a new Constitution was needed to cure the problem.

The Constitution's Solution

Because the Constitution created a new central government, it addressed primarily matters of federal governance. But it also included these terms:

"No State shall ... coin Money; emit Bills of Credit; make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts; pass any ... ex post facto Law, or Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts ...." (Article I, Section 10, Clause 1).

Let's unpack that language.

First, the ban on states "coin[ing] money" was understood to prevent them from issuing money in any medium — including paper. This prevented states from emitting depreciating paper currency as a debt-avoidance scheme.

Second: A "bill of credit" was a small paper instrument evidencing a state debt. Because people used bills of credit as one kind of paper money, the Constitution prohibited states from issuing them.

Third: The Constitution barred states from passing tender laws. States could no longer require creditors to accept cheap or worthless property in payment of debts.

Fourth: "Ex post facto laws" are retroactive enactments. After the Constitution became public, some people interpreted this term as a ban on debt abolition. During the ratification debates, however, "ex post facto" was clarified to mean only retroactive criminal laws. Still, the ban on ex post facto laws prevented states from enacting measures punishing creditors who previously refused to accept worthless property in payment of debts.

Finally: The prohibition on state laws "impairing the Obligation of Contracts" was designed as a general ban on state debt-cancellation schemes.

As Alexander Hamilton clarified in Federalist No. 80, the Constitution did not prevent state courts from continuing to relieve deserving debtors from obligations incurred through creditor fraud and other unfair practices.

In the years since the Constitution became effective, the Supreme Court has weakened somewhat the prohibition on state laws "impairing the Obligation of Contracts." However, some of the ban still survives.

The Gap in the Constitution

Although the Constitution barred states from abolishing debts wholesale, for the most part it did not extend the same prohibition to the federal government — although a ban on federal ex post facto laws and the Fifth Amendment Due Process Clause did grant some protection against federal retroactivity.

One reason for not barring federal debt relief measures may have been that the federal government was charged with the principal responsibility for waging war. The needs of waging war might require debt readjustment.

Moreover, the Constitution did not authorize (and does not authorize) the federal government to guarantee loans for adolescents so they can swell the coffers of universities, or of any other constituency of the National Democratic Party.

Further, as Madison suggested in Federalist No. 10, the Founders did not believe that a single special interest (in this case the universities and their former students) could become powerful enough to generate this kind of self-serving measure at the federal level.

From my long exposure to the Founders' speeches and writings, I think another reason they did not extend the ban on debt cancellation to the federal government is this: The Founders could not imagine a national leader being so shameless.

Conclusion

History demonstrates that attempts to "cure" a problem by exceeding the federal government's constitutional powers generally lead to more and worse problems. The federal student loan program is a good example.

In an attempt to make college more affordable, the program has had precisely the opposite effect: The flood of federal money has greatly inflated the cost of tuition. It also has created a generation of debtors, and added billions to the national debt.

Now the president's administration of the student loan program threatens to victimize hundreds of millions of innocent people by imposing on them an obligation they did not incur — and from which they in no way benefitted.

The Republican majority in the House of Representatives should respond to the latest Biden announcment by defunding federal student loan programs (aside from Veterans' Benefits), completely and permanently.

Rob Natelson, a former constitutional law professor who is senior fellow in constitutional jurisprudence at the Independence Institute in Denver, authored "The Original Constitution: What It Actually Said and Meant" (3rd ed., 2015). He is a contributor to The Heritage Foundation's "Heritage Guide to the Constitution."

Comment: Many seem to believe that student debt relief just magically makes the debt disappear and no one is hurt. But at the end of the day, somebody pays.

See also: