A re-analysis of finds from Soviet-era archaeological digs in Dzhetyasar, Kazakhstan, by archaeologist Dr Azilkhan Tazhekeevat, identified blocks of wood found in 1973 to be a musical instrument, with further analysis confirming it as a 4th century CE lyre.

It is the same type of lyre as the one found as part of the Sutton Hoo ship burial, but dates three centuries earlier than the Sutton Hoo lyre, the researchers explained.

A study of the Kazakhstan lyre, and comparison to other instruments of the time, was carried out by independent researcher, Dr Giermund Kolltveit from Norway.

ABOUT SUTTON HOOThe discovery of the Kazakh lyra only came about thanks to researchers taking a new look at excavations from the 1930s to mid 1990s - during the Soviet era.

Located near Woodbridge, Suffolk, Sutton Hoo is home to two burial mounds from the 6th and 7th centuries — the latter a ship burial.

The undisturbed burial site is believed to have been the resting place of King Rædwald of East Anglia.

The vessel is oft dubbed a a 'ghost ship' thanks to how only its iron rivets and impressions of timber remained.

Within the ship, however, archaeologists in 1939 found a ceremonial helmet, a shield, a sword, pieces of silver plate from the Byzantine Empire and metalwork fittings made of gold and gems.

The Sutton Hoo artefacts are now housed in the collections of the British Museum, London, while the mound site is in the care of the National Trust.

The discovery of Sutton Hoo was recently dramatized in the Netflix historical drama 'The Dig'.

In 1973, these excavations found a series of wooden objects from a medieval settlement in the Dzhetyasar territory, southwest Kazahkstan and the archeologists of the time had no way to identify them further.

While Dr Tazhekeev was able to confirm them as a musical instrument, this study confirmed it to be a lyre - and one that matches the Sutton Hoo burial.

'I was stunned by the instrument's resemblance to lyres from Western Europe, known from the same period,' said Dr Kolltveit.

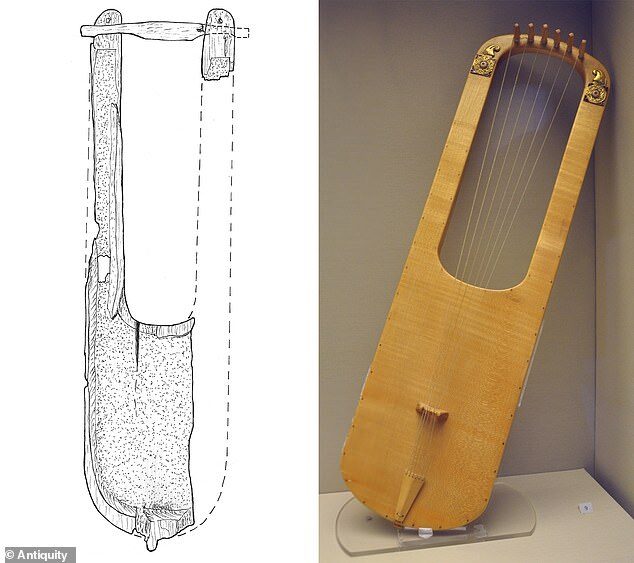

This type of lyre is long and shallow with a single-piece soundbox that has parallel sides and a curved bottom, differing from classic lyres.

When the lyre from Sutton Hoo was found in the 1930s it was initially identified not as a lyre, but a small harp, because of its differences.

Since then more lyres like it have been found, such as an almost intact example from Trossingen, Germany, confirming there was a unique style of lyre in the region.

Other finds suggest this type of lyre may predate the Romans, although most examples are from the early medieval period like the instrument from Sutton Hoo.

'Until now, lyres of this type — famously known from the Sutton Hoo ship burial and the warrior grave in Trossingen, Southern Germany — are not known outside Western Europe at all,' said Dr Kolltveit.

'As such, the identification of strikingly similar instrument 4,000 km away is groundbreaking news.'

The lyre from Dzhetyasar has a matching soundbox, arms, and crossbar to its western cousins.

Dating to around the 4th century CE, it also fits within the time frame of the northern European lyre.

'[If] it had been discovered in an Anglo-Saxon cemetery, or indeed anywhere else in the West, the Dzhetyasar lyre would not have seemed out of place,' Dr Kolltveit said.

Despite being found thousands of miles from the Sutton Hoo version, it could help tackle questions that have long remained over this lyre type.

This includes where it originates, the musical tradition it belongs to and whether it is unique to Northern Europe.

Dzhetyasar is an important site on the Silk Road, the trade route connecting east and west, raising the possibility that the lyre travelled along this route.

There is suggestion the lyre style could have reached Byzantium, the Levant, or even further east than Kazahkstan.

'I hope that we can cooperate with Kazakh archaeologists and bring together a team for a thorough study of this single instrument, said Dr Kolltveit.

He added that 'we still don't fully understand' the instrument a technological point of view.

The researcher said that future re-analysis of Soviet- era digs could help flesh out the history of this instrument, and others from the time.

The Sutton Hoo lyre may have a much deeper, more global history than anyone expected, hinting at a more interconnected musical world in the medieval period.

The findings have been published in the journal Antiquity.

Comment: At various times in history the evidence demonstrates that our world has been much better connected than was formerly believed:

- Burial practices point to an interconnected early Medieval Europe

- Prehistoric Scotland was culturally divergent before the Romans arrived

- Exquisite Bronze Age tomb goods in Cyprus reveal international trade networks

- Staffordshire hoard revealed to be most important Anglo-Saxon find in history

Also check out SOTT radio's: