You and a fire ant have something in common: you can both smell dirt, and, odds are, you both like it.

Although most humans agree that fresh dirt smells sweet, that is not a view universally shared. Fruit flies hate the smell, apparently because it signals spoiled food.

On the other hand, mosquitoes like dirt smell and use it as a cue for egg laying. And as I wrote last spring, tiny arthropods called springtails think dirt not only smells great, it's the smell of steak night at the Sizzler.

The reason, as I wrote here earlier this year, is that dirt doesn't smell like dirt. It smells like bacteria — actinobacteria, to be precise. These bacteria generate the odors we think of as characteristic of dirt to ring the dinner bell for springtails to come eat and disperse their spores.

Why fire ants think dirt smells good, and how we even came to investigate this unorthodox question, is a different story.

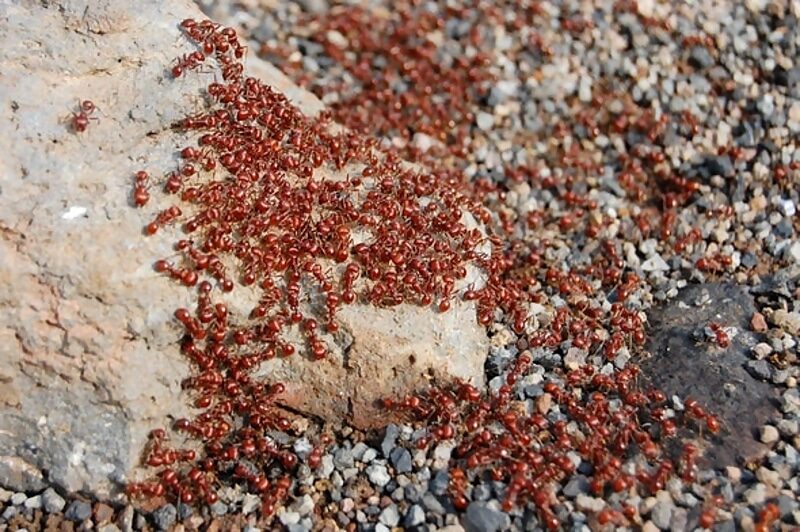

For those of you keeping track at home, fire ants are one of the original nasty invasive species, up there with Dutch Elm Disease, salt cedar and dandelions. The South America natives were introduced to the southern United States in the 1930s, and have proceeded to take over most of the Southeast, to the lasting distress of all the other inhabitants. Fire ants are notorious for swarming and stinging, and their name is an apt description of the result of an encounter.

They're also notorious for their extraordinary resilience. Nest gets flooded? No problem. Simply join legs to form a giant ant raft and float to safety, a strategy that evolved on the flood plains of South America. Such ant balls were spotted floating in the floodwaters of Hurricane Harvey.

Over the last 90 years, fire ants have irrevocably altered the southeastern United States. Some 30-60 percent of the human population there is stung every year, to say nothing of the wildlife and livestock. In their quest for protein, swarms can kill calves and strip the bones. The ants have displaced many native species, reduced biodiversity, spread disease and even likely caused one species of lizard to evolve longer legs just to provide more leverage for flinging them off.

The costs are not just physical. Fire ants cost the U.S. around $6.5 billion annually on a combination of control, medical treatments, livestock and crop loss, and vet bills. We are not alone in our suffering. In just the last 20 years, fire ants have colonized China, Taiwan, New Zealand, Hong Kong, Macao, the Caribbean and Australia.

That unfortunate turn of events may be what prompted Chinese scientists to take a look at the vital question of fire ant real estate preferences in research published in September in the journal PLOS Pathogens. Because it turns out that fire ant queens have strong opinions, and one of their highly-desirables is, apparently, dirt perfume.

In China, scientists observed that some soils seemed to be favored by fire ant queens. To investigate, the scientists placed samples of favored and nonfavored soils at the end of a Y-junction olfactometer in which each arm was scented by a different dirt. Many more workers and queens ended up in the favored soil arm.

The scientists next tested favored soil for the chemical compounds actinobacteria make that give dirt its earthy smell: geosmin and 2-MIB. Favored soil was rich in both. Then they tested the ants' attraction to purified geosmin and 2-MIB. Many more ants ended up in the tube arms scented by these chemicals than in control arms. Ant antennae also produced an electrical response to both chemicals.

Upon probing the dirt's bacterial content, favored soil was enriched in actinobacteria compared to the non-favored soil. From this dirt, the team isolated two strains of Streptomyces and one of Nocardiopsis, both types of actinobacteria. When they spiked nonfavored soil with just these bacteria, it suddenly attracted ants.

So why might actinobacteria be so alluring to fire ants?

These microbes are renowned for their antibiotic prowess. Most of our antibiotic medicines were discovered in such bacteria; streptomycin, for example, unsurprisingly hails from Streptomyces. Actinobacteria are also talented manufacturers of antifungal chemicals. Since soil bacteria have to compete with many other bacteria and fungi, a well-stocked chemical arsenal helps actinobacteria thrive.

Just as antibiotics work as well for us as they do for bacteria, antifungals sprayed indiscriminately by actinobacteria may aid soil insects. Any fire ant that can smell actinobacteria — essentially eavesdropping on their conversation with springtails — could reap an advantage by shacking up with them.

To investigate that possibility, the scientists tested both soil types for fungal animal and insect pathogens. They were enriched in nonfavored soil and impoverished in favored soil. In laboratory experiments, fire ant queens also survived better in favored soil than in nonfavored soil. Yet when nonfavored soil was simply mixed with the Streptomyces and Nocardiopsis bacteria they had isolated from favored soils, queens survived better.

The scientists also watched the corpses of queens that had kicked the bucket in nonfavored soil, and discovered they sprouted insect pathogenic fungi about seven days after death. On the other hand, dead queens from favored soil grew either harmless decomposition fungi or none at all.

Finally, they grew the insect pathogenic fungi isolated from dead queens in culture dishes with their isolated strains of Streptomyces and Nocardiopsis bacteria, and discovered the bacteria inhibited the growth of the fungi.

So to fire ant queens, the smell of dirt may be the smell of a freshly scrubbed kitchen and bath with neatly folded towels, an air purifier, a dehumidifier, a couple of cute rubber duckies and a nonironic toilet paper cozy. Or something like that. For them, the smell of dirt is the smell of home sweet home.

Jennifer Frazer is an AAAS Science Journalism Award-winning science writer. She has degrees in biology, plant pathology/mycology and science writing, and has spent many happy hours studying life in situ.

Reader Comments

Make some art from the buggers, mate! [Link]

interesting reading !

ton ami

septième et dix-huitième alphabétiquement, avec 🐜

😊

(from Ch 7)

The Master stays behind;

that is why she is ahead.

She is detached from all things;

that is why she is one with them.

Because she has let go of herself,

she is perfectly fulfilled.

(Ch 18)

When the great Tao is forgotten,

goodness and piety appear.

When the body's intelligence declines,

cleverness and knowledge step forth.

When there is no peace in the family,

filial piety begins.

When the country falls into chaos,

patriotism is born.

(hint: what do ants and well water dowsers have in common)