The woman's skull had three distinct injuries, indicating that something hard hit her, breaking the skull bones. Her skull was also pitted with crater-like deformations, lesions that look like those caused by a bacterial relative of syphilis, a new study finds.

"It really looks as if this woman had a very hard time and an extremely unhappy end of her life," study lead researcher Wolfgang Stinnesbeck, a professor of biostratigraphy and paleoecology at the Institute for Earth Sciences at Heidelberg University in Germany, told Live Science in an email. "Obviously, this is speculative, but given the traumas and the pathological deformations on her skull, it appears a likely scenario that she may have been expelled from her group and was killed in the cave, or was left in the cave to die there."

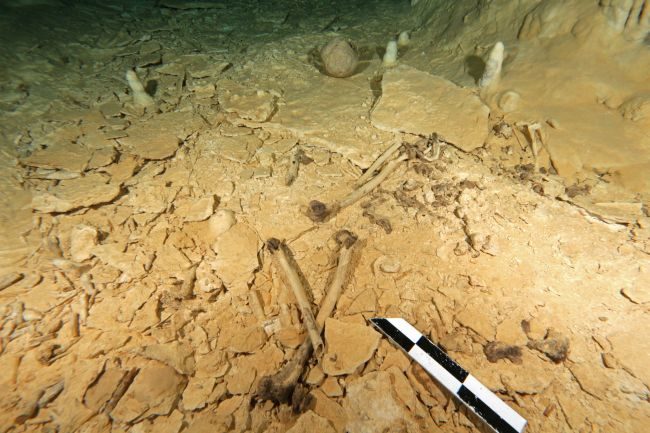

Cave explorers Vicente Fito and Ivan Hernández found the woman's remains in September 2016 while diving in the Chan Hol cave near Tulum. At the time, they were searching for another ancient skeleton known as Chan Hol 2, whose remains, except for a few bones, were stolen by thieves.

The newfound bones were located just 460 feet (140 meters) away from the Chan Hol 2 site, prompting archaeologists to assume that the divers had found the missing Chan Hol 2 remains. But an analysis soon proved them wrong; a comparison of the new bones to old photos of Chan Hol 2 showed "that the two must represent different individuals," Stinnesbeck said.

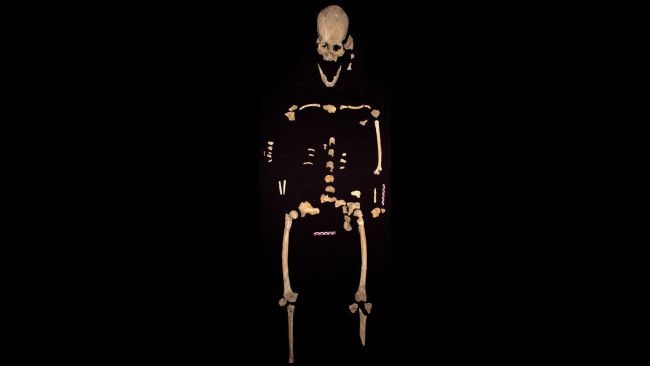

So, an international team got to work analyzing the mysterious skeleton, dubbed Chan Hol 3. While the skeleton is only about 30% complete, the researchers were able to discern that it belonged to a woman who stood roughly 5 feet, 4 inches (1.64 m) tall and was about 30 years old when she died.

What happened to her skull?

The three injuries on the woman's skull hint that she had a violent end, Stinnesbeck said. "There are no signs of healing of these wounds, but it is still difficult to say whether she died from these wounds or survived the blows [for] some time," he said.

It's even less straightforward how her skull developed its dents and crater-like deformities, the researchers said. Perhaps she had Treponema peritonitis, a bacterial disease related to syphilis, which would make this the oldest known instance of this disease in the Americas, the researchers said. If that was the case, "she would have had an inflamed area where the infection was that would have been very sore to the touch, with possible breaks in the skin," study co-researcher Samuel Rennie, a biological and forensic anthropologist, told Live Science in an email.

Or maybe the woman had severe bone inflammation or periostitis, an inflamed periosteum, the connective tissue that surrounds bone, Stinnesbeck said.

Researchers study the remains of the woman from the Chan Hol cave, discovered in Mexico's Yucatán Peninsula. Study co-researchers Silvia Gonzalez (left), a professor in the School of Biological and Environmental Sciences at Liverpool John Moores University in the U.K., and Samuel Rennie, a biological and forensic anthropologist, compare the ancient woman's skeleton with other contemporary skeletons from central Mexico and Brazil. (Image credit: Jerónimo Avilés Olguín)

Dental problems

Like other Tulum cave skeletons, Chan Hol 3 has a distinctive skull.

An in-depth cranial analysis of 452 skulls, taken from 10 different early American populations, showed that "the ancient skeletons from the Yucatán (including the newly discovered Chan Hol 3) had skulls that were different than any of the other places we compared to," Rennie said. He noted that Chan Hol 3 had a slightly longer and narrower brain case (the part of the skull that holds the brain) and a slightly narrower face than other ancient people in Mexico.

In effect, this suggests that there were at least two different groups of humans living in what is now Mexico at the end of the last ice age, Rennie said. This finding reinforces the conclusions of another recent study in the journal PLOS One, which also looked at the remains of ancient people (although not Chan Hol 3) who lived on the Yucatán Peninsula.

Comment: For more on that study on the diversity of the inhabitants: Ancient skulls from Mexico surprisingly diverse, challenges assumptions about settlement of the Americas

In addition, all of the Tulum cave skulls, including the newfound woman's skull, had cavities in their teeth. This suggests that this population had a diet high in sugar, likely from tubers and fruits, sweet cactus, or honey from the native, stingless bees, Stinnesbeck said. In contrast, other populations of early Americans tended to have worn teeth without cavities, indicating that these people likely ate hard foods that were low in sugar, the researchers said.

These dental and cranial differences suggest that "the Yucatán settlers formed a group which was isolated from the hunters and gatherers that populated central Mexico at the end of the Pleistocene," an epoch that ended about 11,700 years ago, Stinnesbeck said. "The two groups must have been very different in aspect and culture. While the groups from central Mexico were tall, good hunters, with elaborate stone tools, the Yucatán people were small and delicate, and to date, not a single stone tool was found."

Dating the woman's remains proved challenging, given that her collagen had decayed long ago in the underwater cave. (Of note, the cave was likely above water when the woman died, the researchers said.) So, the researchers looked at uranium-thorium isotopes in a stalagmite that had become encrusted in the woman's finger bones. (Isotopes are variations of an element that differ in the number of neutrons in their nuclei.) The same uranium-thorium method was used to date the remains of the Chan Hol 2 skeleton, which was estimated to be up to 13,000 years old.

While this method isn't the gold standard for dating human remains, it does help researchers get close to the actual date.

"Unfortunately, many of these skeletons, including the one described here, lack sufficient collagen for conventional radiocarbon analysis," Justin Tackney, an associate researcher of anthropology at the University of Kansas who wasn't involved with the study, told Live Science in an email. "Creative dating of some, but not all, of these individuals will be called into question, but this is offset by the slowly accumulating publications of each new individual described."

Granted, it appears that the researchers did all they could to date the specimen, given the constraints, said Gary Feinman, the MacArthur curator of Mesoamerican, Central American and East Asian anthropology at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, who wasn't involved with the study.

That said, there "has to be kind of at least a small question mark about exactly how old these skeletons are," Feinman told Live Science.

The study was published online today (Feb. 5) in the journal PLOS One. Originally published on Live Science.

RC

*(Like what is being done to the West.)