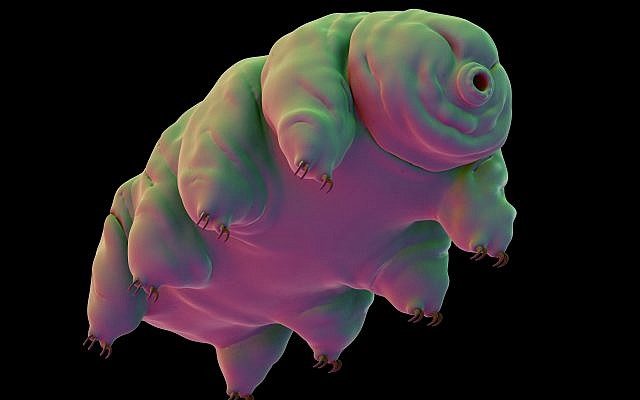

According to a report published Monday by American magazine Wired, however, Beresheet may have left more on the Moon than previously thought. The SpaceIL spacecraft was apparently carrying thousands of microscopic tardigrades, also known as "little water bears," which are among the most resilient animals known to man.

The tardigrades, only 0.5mm in length when fully grown, joined the lunar-destined journey as part of an initiative led by the Arch Mission Foundation, founded by Nova Spivack.

Aiming to maintain a backup of planet Earth around the Solar System, Beresheet carried the foundation's lunar library - a tiny 30-million page archive of human history and civilization, human DNA samples and a few thousand dehydrated tardigrades.

Based on the foundation's analysis of the spacecraft's trajectory and the composition of their lunar library, Spivack told Wired that he was quite confident that their payload mostly or entirely survived the impact.

Engineers lost contact with the spacecraft only minutes before it was due to complete the historic lunar landing on April 11, making a high-velocity crash-landing inevitable. Reaching the moon was a feat previously completed only by the United States, Russia (then the USSR) and China, backed by giant sums far exceeding Beresheet's modest NIS 350 million ($99m.) budget.

"For the first 24 hours, we were just in shock," Spivack said. "We sort of expected that it would be successful. We knew there were risks but we didn't think the risks were that significant."

Known for their resilience, a 2007 European Space Agency experiment showed that tardigrades are able to survive space exposure. Some 3,000 organisms joined a 12-day journey into space on-board the agency's Foton-M3 mission, and survived conditions that would kill humans in minutes.

If the dehydrated tardigrades survived the landing, Spivack added, they could hypothetically be revived in years to come by future human astronauts upon their return to Earth. Research has previously shown that dehydrated micro-animals can be revived decades later.

While SpaceIL and its lead donor, Morris Kahn, quickly stated their ambition following the Beresheet crash to launch a second spacecraft to the Moon within two years, the organization announced in June that reattempting the same mission would not present a sufficiently great challenge.

If some lunar enthusiasts might have been disappointed by the announcement, SpaceIL co-founder Kfir Damari told The Jerusalem Post in July that the decision is about broadening their horizons even further.

"It's possible that we will return to the Moon, but we won't give a green light to the same project with the same design," Damari said.

"We decided that we want to look for different options - maybe to go to the Moon and come back or to take something special with us. We're also thinking about other places, including the ability to go beyond the Moon."

It remains to be seen whether SpaceIL's next mission will include taking even more tardigrades to the Moon, or perhaps even beyond.

Comment: See also: