Spices are causing a stir as cheap and easy cure-alls for everything from diabetes to dementia, but not all the claims live up to the hype

Turmeric and bread makes for an unusual breakfast. But when Mark Wahlqvist served it to a group of older people in Taiwan, he had high hopes. They had been diagnosed as heading for diabetes, which can affect mental abilities. Having heard that the spice could have cognitive benefits, he wanted to put it to the test. "The idea that turmeric might be brain-protective is novel," says Wahlqvist, currently at the National Health Research Institutes in Taipei, Taiwan.

To those following the latest food trends, however, the spice's brain-boosting potential is unlikely to raise an eyebrow. It is just one in a long list of turmeric's supposed benefits that have seen it proclaimed as a cheap and effective super food. As a result, what once may have been gathering dust in your spice rack is now the star attraction at trendy coffee shops selling "golden lattes".

Other spices are vying for popularity, too. From cinnamon to saffron, the internet is rife with claims about the healing powers of spices, suggesting that they can help with just about any condition from depression to cardiovascular disease and cancer. Even Hillary Clinton has reportedly jumped on the bandwagon. After reading that hot peppers can boost the immune system, she was eating one a day during the 2016 US presidential election campaign in an attempt to improve her stamina. The question is whether we are swallowing anything more than a load of hype.

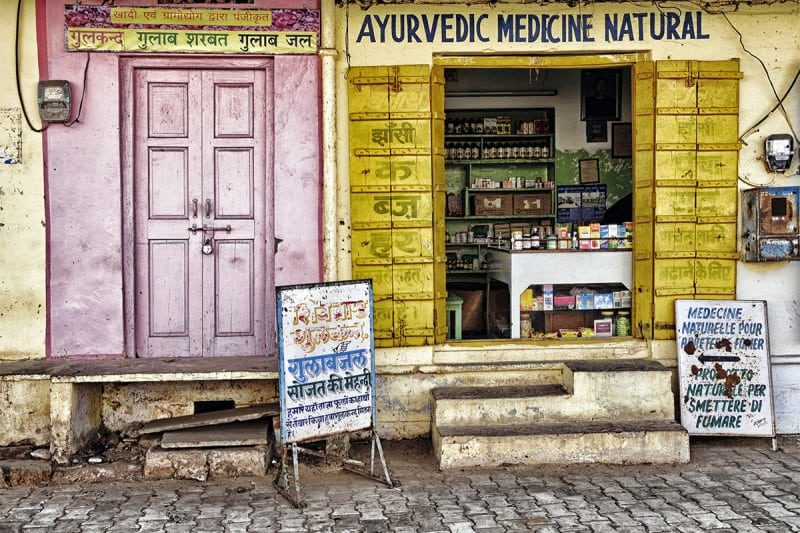

300%The promise of the medicinal benefits of spices is rooted in traditional medicine. In holistic Ayurvedic medicine, which has been practised for more than 3000 years in what is now India, turmeric is mixed with milk as a remedy for colds or made into a paste that is applied as a topical treatment for sprains or inflamed joints. More than 300 herbs and spices are used in Chinese medicine, where cinnamon is the go-to option for those wanting relief from muscle pain, as well as being recommended to control excessive sweating, among other ailments. Spices may be added to food or steeped in liquid as a medicinal drink, often in combination.

Increase in Google searches for turmeric between 2012 and 2016

Source: Google Trends, US

The allure of these therapeutic properties spread as herbs and spices were introduces to Europe from Asia and Africa in the Middle Ages, and has blossomed as more immigrants settled in Europe in the 20th century, says Wahlqvist. But in the past few years, as our appetite has grown for functional foods - those with health benefits beyond their nutritional value - spices have reached cult status. In Europe, imports of spices and herbs have increased by 6.1 per cent annually between 2012 and 2016. Google searches for turmeric shot up 300 per cent in the US over this period. And sales of supplements of curcumin, an active ingredient in turmeric, reportedly raked in over $20 million in 2014.

In perhaps the largest study to date, Liming Li at Peking University in Beijing, China, and his colleagues followed 480,000 apparently healthy adults in China for about seven years. They found that those who ate chilli peppers almost every day were 14 per cent less likely to die in that time than those who consumed them less than once a week (see "Hot tip").

If the effects are real, what is it about spices that makes them so healthy? Many of the claims are based on the idea that they contain powerful antioxidants. As our bodies break down the food we eat, they produce rogue molecules called free radicals that contribute to ageing and disease. Antioxidants are often thought to be able to mop these up.

Spices are rich in polyphenols, a group of plant compounds thought to have antioxidant properties. This is what first piqued the curiosity of Elizabeth Opara at Kingston University in the UK. "It seems that when you categorise different foods based on antioxidant capacity, herbs and spices are right at the top," she says.

But don't reach for your golden latte just yet. Later research found that consuming herbs and spices led to no increase in antioxidant activity in people's blood. "Work now suggests that if polyphenols have any benefits at all, they aren't linked to the ability to curb antioxidants," says Opara. This highlights one big problem with much of the research on spices: it is often done in the lab, and what looks promising in a cell sample rarely bears out in the human body.

Other studies in people look more promising, though. For their breakfast experiment, Wahlqvist and his colleagues wanted to see whether the quantities of turmeric and cinnamon typically eaten in food might help with memory impairment that develops with prediabetes. Some work suggests that cinnamon can lower insulin resistance, which could help control blood sugar levels and guard against the associated neurodegeneration. In their study, a group of 48 people with prediabetes received one of four breakfasts: 1 gram of turmeric, 2 grams of cinnamon, both spices or a placebo, along with a serving of white bread - a nutritionally inert filler that would allow the researchers to isolate the potential effect of the spices.

Those who ate the turmeric breakfast had improvements to their working memory 6 hours later. Tests of this kind of memory are used to predict cognitive decline. There were no memory changes in the other groups.

Just because there seems to be a relationship between the spice and memory doesn't mean that it is causing the change, however: other factors that weren't controlled for could be at play. And the study only included people who eat a Chinese diet, which could affect results. What's more, the team doesn't know whether changes are long-lasting or how turmeric could be having an effect.

Comment: While this is true, one wonders if pharmaceutical medications are subject to the same scrutiny when the study shows benefits.

$20mPerhaps chemical compounds in turmeric can provide clues. Assessing the effect of spices as food can be complicated by the fact they are consumed in small quantities as part of a much wider diet. So Gary Small at the University of California, Los Angeles, and his colleagues homed in on the powers of curcumin supplements. Making up about 3 per cent of turmeric, curcumin has become a buzzword in itself and is widely sold as a dietary supplement. More than 120 clinical trials have tested its effectiveness against numerous conditions, from Alzheimer's disease to erectile dysfunction.

Worth of curcumin supplements were sold in the US in 2014

Source: Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, Vol 60, p 1620

Comment: Green Med Info has amassed 2567 studies showing turmeric to be beneficial for everything from oxidative stress to obesity and even cancer.

In a study published earlier this year, Small's team looked at its long-term effect on cognitive abilities in people middle-aged and older with mild, age-related memory issues. One group of 40 took a pill containing 90 milligrams of curcumin twice a day. Another group received a placebo. Both were given cognitive tests every six months over 18 months and some people received brain scans.

The team found that the memory and mental focus of those taking curcumin improved significantly, while there was no difference for the others. The amount of plaques and tangles of proteins - thought to be a cause of cognitive impairment - in brain regions that modulate mood and memory also fell. "I was pleasantly surprised that it worked in a relatively small sample," says Small.

He suspects that curcumin could be provoking an anti-inflammatory response. Inflammation is the body's response to injury or infection, but modern living can make it go awry by constantly triggering the process. This has been implicated in conditions ranging from heart disease to depression.

Reducing inflammation in the brain to dampen down swelling could allow neural cells to function better. This may be connected to the reduction in tangles Small's team observed. If so, he thinks curcumin pills could be an alternative for people who struggle to make lifestyle changes, such as improving their diet or exercising more. "It's hard for people to change their behaviour," says Small. "Here we're just asking people to take some capsules a couple of times a day."

He and his team now plan to follow up with a larger study to confirm the effect. They also found a modest mood boost in the group given the curcumin, something they would like to probe further by including participants with mild depression. In some cases, plaques and tangles have been observed in people who have low mood but not dementia. "We would like to understand that more," says Small.

Not everyone is convinced about curcumin, however. Last year, Kathryn Nelson at the University of Minnesota and her colleagues, who validate new chemicals that could be developed into drugs, published a scathing review of curcumin's supposed health benefits. "Curcumin research may have entered the steep section of the hyperbolic black hole of natural products where effort rapidly exceeds utility," they wrote.

One of the biggest criticisms is what they call the "dark side" of the spice: it seems to have an effect in so many studies, which may be due to false positives. "If a chemical is active in every test, that's a red flag," says Nelson. "It means that it might not really be active in any of them."

Comment: Do we notice a pattern here? Talk about the benefits scientists have found studying turmeric/curcumin only to shoot it down via expert in the next paragraph.

When hunting for drug candidates, preliminary lab experiments look at whether a chemical is able to bind to a protein implicated in a disease. But some chemicals can give false signals. Curcumin is one of them. For instance, it can disrupt cell membranes, making it seem like it is interacting with proteins on a cell's surface. In various solutions, it also seems to fluoresce, which is often sought out as a marker of activity. Curcumin has appeared to have an effect in drug screening for many conditions, yet it has never led to a proven treatment.

There are even questions about whether enough of the stuff is absorbed into the body to do anything. "Even when you give people up to 12 grams a day of curcumin, you can't find it in their bloodstream," says Nelson.

Comment: And how does any of the above explain improvement in memory? It was a placebo-controlled experiment, remember. It seems the scientitians always shoot things down when they can't explain a mechanism of action (ahem, homeopathy), but just because we can't explain how something works doesn't mean it doesn't work.

Retracted evidence

Human error plays a part, too. Several papers by Bharat Aggarwal, formerly at the University of Texas, laid the groundwork for clinical trials looking at the effect of curcumin on cancer, but were later retracted.

As for cinnamon, a review of randomised trials of its effects on diabetes had to discard most identified studies because of the risk of bias. From the scant studies remaining, it concluded there was no strong evidence of any health effects.

That doesn't mean spices are a lost cause - but a lot more evidence is needed before we should take them seriously. And there may be beneficial effects we simply haven't discovered yet. Take the case of artemisinin, currently the most effective malaria treatment. The Nobel prize-winning discovery was made by screening 2000 remedies from Chinese medicine.

50Topical uses of spices should have more scope since active ingredients don't need to be absorbed into the bloodstream to work. Several teams are looking at the potential antimicrobial properties of spices, and even incorporating them into packaging to preserve food. "People are using curcumin as a supplement and that's not what traditional medicine was doing to start with," says Nelson.

New manuscripts are published about curcumin each week

Source: Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, Vol 60, p 1620

Besides, there are other good reasons to fall in love with the contents of your spice rack. While they might not live up to their reputation as a cheap and easy panacea, spices have now been added to national dietary guidelines in both the US and Australia that previously focused on staples such as meat, carbohydrates, fruit and vegetables. Why? Adding spices to food is an easy way to cut down on salt, which can raise blood pressure. A diverse diet is widely recommended as the healthiest way to eat and variety, after all, is the spice of life.

Lethal ingestion

The intense burning sensation you get when eating hot chilli peppers can feel all-consuming, but can consuming spices ever prove fatal? Potentially. In one rare case, a man who was eating ghost peppers - one of the world's hottest varieties - as part of a competition started being sick and complained of chest pain. It turned out that the force of vomiting had ruptured his oesophagus and he required surgery. Without medical attention he would probably have died.

Nutmeg, which is sometimes used as a recreational drug, could be risky too. It contains myristicin, a volatile oil that can have hallucinatory and amphetamine-like effects when broken down in the body. One student looking for a cheap high ended up in hospital after blending 50 grams of the spice into a milkshake. Even such a high dose is unlikely to be fatal, but there are a few reported deaths from overdosing on the spice.

And while there is little chance of you ingesting too much of a spice by accident - "I don't think anybody has to worry about eating too much curry," says Kathryn Nelson at the University of Minnesota - spice supplements, which contain higher doses of active ingredients, can cause problems by interacting with medications. Curcumin, for example, is thought to thin blood and so should be avoided when taking anticoagulant medications.

Supplements are often self-prescribed, and people may feel that because they are sold as natural remedies they are harmless. However, in most cases scientific research has yet to determine their benefits and side effects.

Comment: While it shouldn't be assumed that all natural remedies are harmless, in general, the side-effects are minimal to non-existent. But one should always consult a knowledgeable practitioner and do some research before taking a supplement, especially if one is on medication.

Hot tip

The active ingredient in hot chilli peppers is the heat-producing compound capsaicin, which is thought to help the plant deter herbivores from eating it.

Those brave enough to ingest it could find their fat melting away as a result. Masayuki Saito at Tenshi College in Japan and his colleagues have been looking at how capsaicin can activate brown fat. Whereas the more common white fat stores energy from food, brown fat turns food straight into body heat. Research suggests that cold triggers brown fat to convert more of the food to heat, resulting in weight loss. Capsaicin seems to mimic this effect. In a trial, Saito's team found that the brown fat in healthy young men given 1.5 milligrams of capsaicin became activated, burning more energy than a group given a placebo.

You don't have to eat chillies to reap other benefits from capsaicin, however. In a study of more than 550 adults experiencing numbness and burning pain due to nerve problems, Maija Haanpää at the Helsinki University Central Hospital in Finland and her colleagues found that a skin patch containing capsaicin applied to the affected area could provide as effective pain relief as an oral medication - but faster and with fewer side effects.

If you grow chilli peppers hot enough, their numbing power could even be used as an anaesthetic. Last year, the hottest pepper ever was grown in the UK, coming in at 2.48 million units on the Scoville scale; the previous record was 1.6 million. Now, researchers at Nottingham Trent University in the UK want to see if they can extract the oil from the chilli and use it to numb the skin. This could be especially useful as a cheaper alternative to existing local anaesthetics in developing countries.

oh darn, they can't figure out how to turn a useful herb into a patent-able drug, and it doesn't even show up in the blood! Obviously, it must be useless, or maybe even dangerous, because we can't make money from it.