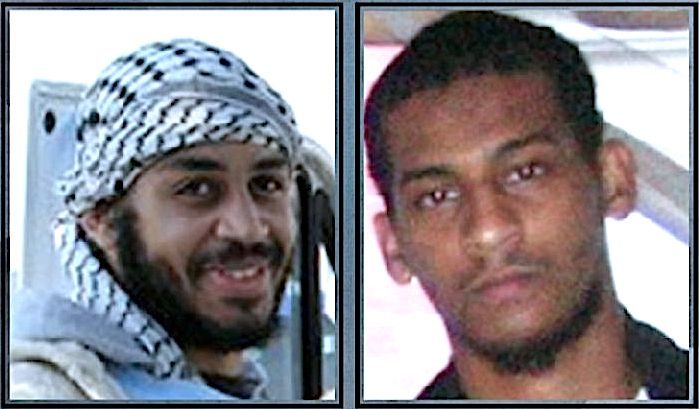

© worldjusticenews.comAlexanda Kotey • El Shafee Elsheikh

Justice Department leaders are reluctant to recommend U.S.-based criminal trials for two Islamic State militants captured and detained in Syria, according to American officials who said that, even though federal prosecutors believe they can win in court, it is unclear whether there is sufficient evidence to secure convictions and lengthy prison terms.

At the same time, senior Trump administration officials are adamant that

Britain bears responsibility to prosecute the men, Alexanda Kotey, 34, and El Shafee Elsheikh, 29, whose British citizenships were revoked over their alleged affiliation with an ISIS cell suspected of murdering Westerners.Further complicating matters,

Attorney General Jeff Sessions would prefer that Kotey and Elsheikh be sent to the U.S. military detention facility in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, though he has recognized the success of federal terrorism prosecutions.

State Department officials are wary of undermining the U.S. government's position that terrorist fighters captured overseas should be returned to their countries of origin.

The complicated U.S. policy discussion, and the impasse between the United States and Britain, is testing the patience of the victims' families, who anxiously await a decision they hope will result in justice through a fair and open trial.

They oppose sending the men to Guantanamo, which they view as fuel for terrorists' narrative of abuse and mistreatment by U.S. authorities.Slowing the process is a turnover in leadership in London, where a new Home Secretary just took office, and in Washington, where John Bolton last month became President Donald Trump's national security adviser.

"We really don't have any commitment that the U.S. is going to actually take on their case," said Diane Foley, whose son, journalist James Foley, was beheaded by the Islamic State in 2014. Foley and the relatives of three other deceased American hostages met in recent days with Bolton and Assistant Attorney General for National Security John Demers. The officials were sympathetic listeners, she said, but they could not offer much guidance. "It's all very much still up in the air," she said.

Trump issued an executive order in January to leave Guantanamo open. At his direction,

Defense Secretary Jim Mattis has developed criteria for transferring terrorist suspects captured on the battlefield to the prison, including that they be high-value and members of groups such as al-Qaida or the Islamic State. The Pentagon also is eager for the British to take custody of Kotey and Elsheikh, in part to ease the pressure on the United States' main ally in Syria, the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces, which has become taxed by having to detain hundreds of captured foreign fighters.

The families, Foley said, hope to speak with Trump and Mattis.

The White House declined to comment, as did the Pentagon, Justice Department and State Department. "We continue to work extremely closely with the U.S. government on this issue . . . in the context of our joint determination to tackle international terrorism and combat violent extremism," a British government spokesman said.

U.S. officials say

Kotey and Elsheikh belonged to a four-person ISIS cell known as the Beatles, so named for the members' British accents.

The group held more than 20 Western hostages and tortured many of them. The most infamous was Mohammed Emwazi, better known as Jihadi John, who was killed in a 2015 drone strike in Syria. The fourth member, Aine Davis, was arrested in Turkey, convicted in 2017 and is in prison there.U.S. prosecutors have told their bosses they have evidence - with the most compelling material coming from Britain - to obtain life sentences on charges such as conspiring to provide material support to terrorists with acts resulting in death, and conspiring to take hostages with acts resulting in death.

In a February memo to Demers, attorneys in the Eastern District of Virginia indicated

the British have voice analysis evidence against Kotey that could link him to the Beatles cell, which is important because the captors wore masks while in the hostages' presence. Investigators believe witnesses would make voice identifications, which might be buttressed by circumstantial evidence, such as showing that the men used phrases around the hostages that they were known to use at other times.

"There is definitely enough evidence to put them on trial," said one British intelligence official, speaking on condition of anonymity to discuss a sensitive matter. The official declined to say how strong he felt the evidence was but added that, if they are convicted and imprisoned, he fears they would "radicalize other prisoners while we would have to pay for their prison time - not a great scenario."

Investigators also have gathered evidence of the men's radicalization dating to the mid-2000s. Neither has denied belonging to the Islamic State.

Prosecutors are hopeful they could build a case that connects both to the murders of Foley, Kayla Mueller, Steven Sotloff and Peter Kassig.But senior administration officials, including some in the Justice Department, are less certain. One obstacle, officials say, is

the British have placed requirements on sharing evidence, including a guarantee that the men will not be sent to Guantanamo and that the death penalty won't be sought.Sessions, alluding to these demands, chided the British government late last month for its reluctance to prosecute the men. "I have been disappointed, frankly, that the British . . . are not willing to try the cases but pretend to tell us how to try them," he said during congressional testimony.

"What happens if we bring them here and the prosecution is not successful?" one U.S. official said, describing the questions often asked within the administration. "Do we just release them onto the streets of southern Manhattan?" And if the United States agrees to prosecute Kotey and Elsheikh, "how does that affect our ability to persuade other countries" to take back their dozens of foreign terrorist fighters if the British don't take their two?

Former national security prosecutors say they would take the risk. "I'd put my money on the assessment of the career terrorism prosecutors recommending federal charges against these guys," said Nicholas Lewin, who successfully tried in the Southern District of New York a number of senior al-Qaida figures.

A presidential directive signed by President Barack Obama in 2015 states that the prosecution of hostage-takers is an important deterrent. The U.S. government, it said, shall seek to ensure they are prosecuted through "a due process criminal justice system" in the United States or abroad.

And we know that long before they could testify, they'd suffer Carcinoma-Rubenstein .*

R.C.

*Ruby's real name.

RC