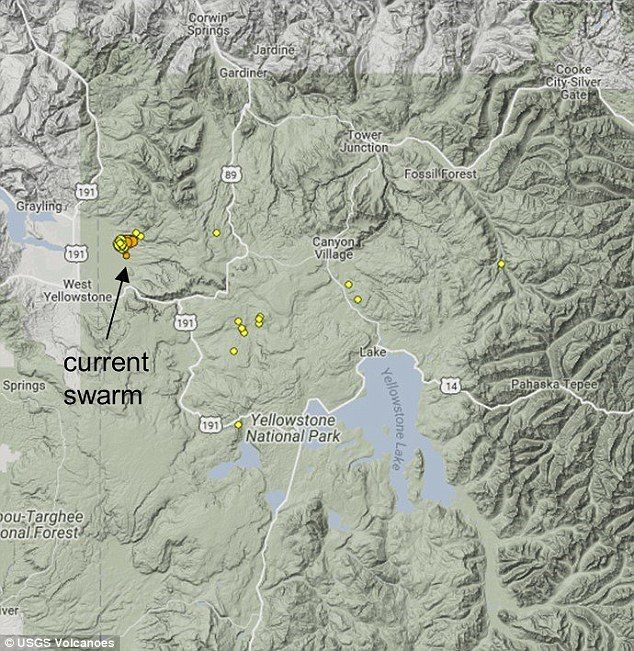

According to experts with the US Geological Survey, the latest swarm began on February 8 in a region roughly eight miles northeast of West Yellowstone, Montana - and, it's increased dramatically in the days since.

But for now, scientists say there's no reason to worry.

While the earthquakes are likely caused by a combination of processes beneath the surface, the current activity is said to be 'relatively weak,' and the alert level at the supervolcano remains at 'normal.'

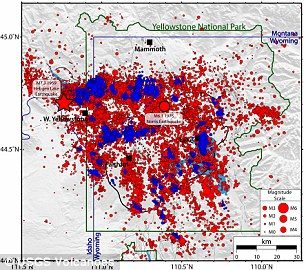

Yellowstone is home to several faults, and has a long history of seismic activity. As natural processes occur beneath the surface and 'stress effects' from past events continue to maintain their hold, the area remains a 'hotbed of seismicity and swarm activity,' according to USGS

The University of Utah Seismograph Stations picked up the first quakes just over a week ago, counting more than 200 as of February 18.

But, the experts say there are likely many more that have gone undetected.

'The present swarm started on February 8, with a few events occurring per day,' according to USGS.

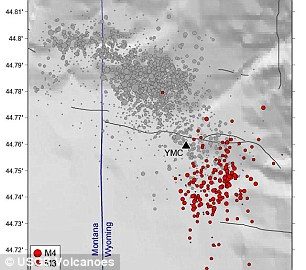

'On February 15, seismicity rates and magnitudes increased markedly. As of the night of February 18, the largest earthquake in the swarm is M2.9, and none of the events have been felt. All are occurring about 8 km (5 mi) beneath the surface.'

Yellowstone is home to several faults, and has a long history of seismic activity.

As natural processes occur beneath the surface and 'stress effects' from past events continue to maintain their hold, the area remains a 'hotbed of seismicity and swarm activity,' according to USGS.

'Swarms reflect changes in stress along small faults beneath the surface, and generally are caused by two processes: large-scale tectonic forces, and pressure changes beneath the surface due to accumulation and/or withdrawal of fluids (magma, water, and/or gas),' USGS explains.

Comment: See:

- Yellowstone super volcano under strain from pressure in magma chamber

- The ground around the Yellowstone supervolcano has deformed after 1,500 quakes this summer

'The area of the current swarm is subject to both processes.'

The current activity, however, is likely no cause for worry.

As the experts explain, earthquake swarms are a common phenomenon at Yellowstone, and account for more than 50 percent of seismic activity at the park.

And in the past, they have not been linked to volcanic activity.

'While it may seem worrisome, the current seismicity is relatively weak and actually represents an opportunity to learn more about Yellowstone,' USGS explains.

'It is during periods of change when scientists can develop, test, and refine their models of how the Yellowstone volcanic system works.'

But, the experts also note: 'The earthquakes, too, serve as a reminder of an underappreciated hazard at Yellowstone - that of strong earthquakes, which are the most likely event to cause damage in the region on the timescales of human lives.'

Could an eruption be prevented?

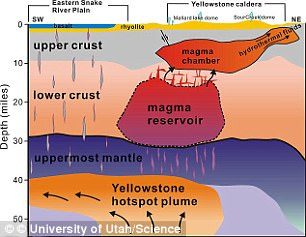

Recent research found a small magma chamber, known as the upper-crustal magma reservoir, beneath the surface

Nasa believes drilling up to six miles (10km) down into the supervolcano beneath Yellowstone National Park to pump in water at high pressure could cool it.

Despite the fact that the mission would cost $3.46 billion (£2.63 billion), Nasa considers it 'the most viable solution.'

Comment: BACK OFF: Geologists slammed NASA over its risky plan of drilling into Yellowstone supervolcano

Using the heat as a resource also poses an opportunity to pay for plan - it could be used to create a geothermal plant, which generates electric power at extremely competitive prices of around $0.10 (£0.08) per kWh.

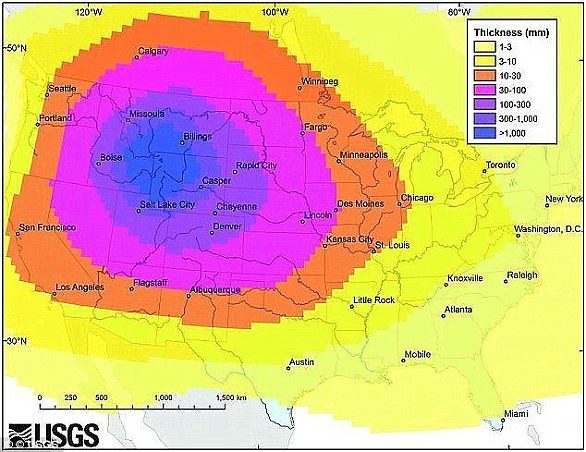

But this method of subduing a supervolcano has the potential to backfire and trigger the supervolcanic eruption Nasa is trying to prevent.'Drilling into the top of the magma chamber 'would be very risky;' however, carefully drilling from the lower sides could work.This USGS graphic shows how a 'super eruption' of the molten lava under Yellowstone National Park would spread ash across the United States

This USGS graphic shows how a 'super eruption' of the molten lava under Yellowstone National Park would spread ash across the United States

Even besides the potential devastating risks, the plan to cool Yellowstone with drilling is not simple.

Doing so would be an excruciatingly slow process that one happen at the rate of one metre a year, meaning it would take tens of thousands of years to cool it completely.

And still, there wouldn't be a guarantee it would be successful for at least hundreds or possibly thousands of years.

Maybe this is the idea. Certainly would get a handle on the population problem.