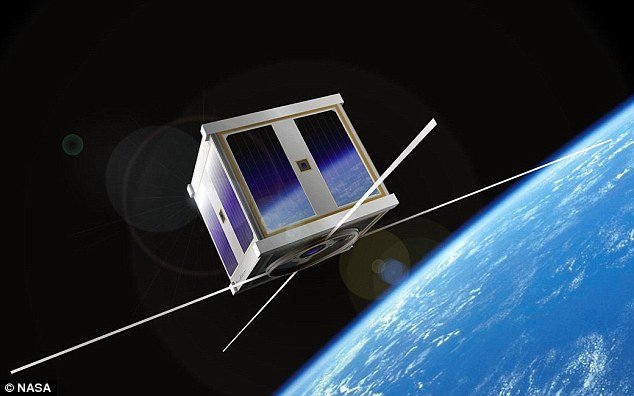

The US Air Force has granted contracts to three research teams to develop the technology needed to do this, with hopes that CubeSats could carry massive amounts of ionized gas to the ionosphere to create radio-reflecting plasma.

The ionosphere begins roughly 40 miles above the surface and becomes denser with charged particles at night, allowing signals to travel much farther.

Ground-based radio signals are limited by the curvature of Earth's surface, and those travelling more than about 44 miles are typically stopped if they aren't given a boost, according to New Scientist.

These communications can be improved by bouncing the radio signals between the ionosphere and the ground, allowing them to zigzag over greater distances.

In one of the USAF-backed projects, researchers with General Science and Drexel University in Pennsylvania are working to develop a way to vaporize metal by heating it beyond its boiling point.

This would allow it to react with atmospheric oxygen to produce radio-reflecting plasma.

Another project from a team at Enig Associates and the University of Maryland plans to heat metal by detonating a small bomb, and converting the blast into electrical energy.

And, the shapes of the plasma clouds could be fine-tuned by altering the form of the initial explosion, New Scientist explains.

In the past, researchers with the High Frequency Active Research Program in Alaska have attempted to create plasma using radiation from ground-based antennas to stimulate the ionosphere.

The new plan from the USAF aims to find a more efficient way.

But, the work does not come without challenges.

For the plans to work, researchers must develop a plasma generator small enough to fit on a CubeSat, and they must find a way to control how the plasma disperse once it's been released.

With these challenges considered, researchers say it's still too early to know if the plan is feasible.

'These are really early-stage projects, representing the boundaries of plasma research into ionosphere modification,' John Kline, who leads the Plasma Engineering group at Research Support Instruments in Hopewell, New Jersey, told New Scientist.

'It may be an insurmountable challenge.'

Vaporizing metal so as to bond with atmospheric Oxygen.

Surely this will have an effect on the already changing climate.

What will be the effects on radiation in the atmosphere and the release of heat?

Sounds like they will create a "hotbox" to transmit radio waves further and to increase their ability to enhance intercepted communications from afar.

"this does not sound good and cannot end well"