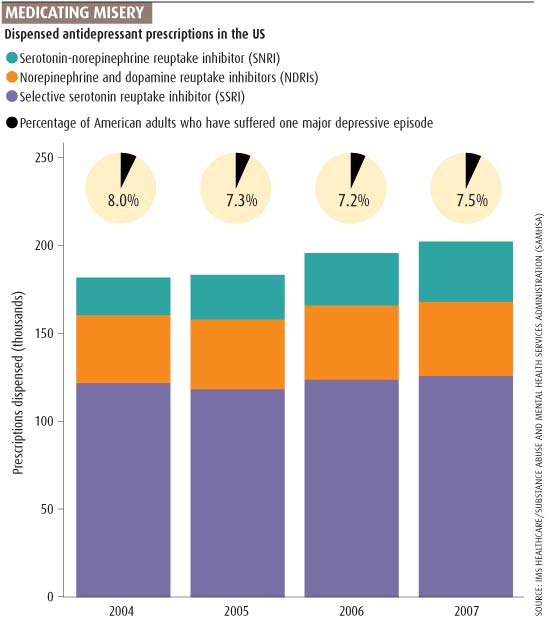

© UnknownMedicating Misery

Why be miserable? OK, so it's January and you're feeling fat and broke after the excesses of the holiday season, but there's really no need. Misery is inconvenient, unpleasant, and in a society where personal happiness is prized above all else, there is little tolerance for wallowing in despair. Especially now we've got drugs for it.

Antidepressants can help banish sad feelings - not just the life-sapping black dog of clinical depression, but the rough patches that most people go through sometimes, whether it's after losing a job, the break-up of a relationship or the death of a loved one. So it's no surprise that more and more people are taking them.

But is this really such a good idea? A growing number of cautionary voices from the world of mental health research are saying it isn't. They fear that the increasing tendency to treat normal sadness as if it were a disease is playing fast and loose with a crucial part of our biology. Sadness, they argue, serves an evolutionary purpose - and if we lose it, we lose out.

"When you find something this deeply in us biologically, you presume that it was selected because it had some advantage, otherwise we wouldn't have been burdened with it," says Jerome Wakefield, a clinical social worker at New York University and co-author of

The Loss of Sadness: How psychiatry transformed normal sorrow into depressive disorder (with Allan Horwitz, Oxford University Press, 2007). "We're fooling around with part of our biological make-up."