We're already 74 days into the new year, which can only mean one thing: it's high time for our latest episode of Science Says Meat Will Kill You, complete with a brand new study and commercial-free viral media coverage! Have a seat and tune in (or at least set your DVR for later viewing).

If you haven't had at least one family member, coworker, or soon-to-be-unfriended Facebook acquaintance send you this study as a reminder that you're killing yourself, you're either really lucky or your inbox is broken. Thanks to an observational study called Red Meat Consumption and Mortality freshly pressed in the Archives of Internal Medicine, a slew of bold headlines exploded across every conceivable media outlet this week:

- All red meat is bad for you, new study says"

- Red meat is blamed for one in 10 early deaths

- Scientists warn 'red meat can be lethal'

And in case that's not enough to chew on, there's more: the researchers waved their statistical wands and declared you could outrun death for a few more years by swapping red meat for so-called "healthier foods" like nuts, chicken, or whole grains. In fact, the researchers suggest that up to one in ten of the deaths that struck their study participants could've been prevented if everyone had kept their red meat intake under half a serving per day!

But if you've been hanging around the nutrition world for very long, you've probably realized by now that health according to the media and health according to reality are two very different things - and even scientific studies can be misrepresented by the researchers who conduct them. Is our latest "killer meat" scare a convincing reason to ditch red meat? Is it time to put a trigger lock on your lethal grass-fed beef when the young'uns are around? Or is there more to this story than meats the eye? (Sorry, I had to.)

Observations vs. Experiments

Before we even dig into what this study found, let's address an important caveat that the media - and even the researchers, unless they were terribly misquoted - seem to be confused about. What we've got here is a garden-variety observational study, not an actual experiment where people change something specific they're doing and thus make it possible to determine cause and effect. Observations are only the first step of the scientific method - a good place to start, but never the place to end. These studies don't exist to generate health advice, but to spark hypotheses that can be tested and replicated in a controlled setting so we can figure out what's really going on. Trying to find "proof" in an observational study is like trying to make a penguin lactate. It just ain't happening... ever.

Nonetheless, the media blurbs - and even quotes from the scientists themselves - suggest this study has a major case of mistaken identity. The lead researcher Frank Hu claimed the study "provides clear evidence that regular consumption of red meat, especially processed meat, contributes substantially to premature death," despite the fact that the study is innately incapable of providing such evidence. It's as if someone pulled a Campbell on us. Only an actual experiment, with controls and manipulated variables, could start confirming causation.

But the study's over-extrapolation isn't really that surprising. A conclusive experiment is what every observational study secretly yearns to be, deep down in its confounder-riddled, non-randomized heart. And like pushy stage mothers, some researchers want their observational studies to be more talented and remarkable than they truly are - leading to the scientific equivalent of a four year old wobbling around in stilettos at a beauty pageant. Our study at hand is a perfectly decent piece of observational literature, but as soon as its authors (or the media) smear it with lipstick and make it sing Patsy Cline songs on stage, it's all downhill from there.

Food Frequency Questionnaires: A Test of Superhuman Memory and Saint-like Honesty

To kick this analysis off, let's take a look at how the study was actually conducted. As the researchers explain, all of the diet data came from a series of food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) that the study participants filled out once every four years, starting in the 1980s and ending in 2006. (If you're feeling brave, you can read the questionnaire yourself (PDF) and try imagining how terribly the average, non-diet-conscious person might botch their responses.) The lifestyle and medical data came from additional questionnaires administered every two years.

The full text of our study offers some additional details (emphasis mine):

In each FFQ, we asked the participants how often, on average, they consumed each food of a standard portion size. There were 9 possible responses, ranging from "never or less than once per month" to "6 or more times per day." Questionnaire items about unprocessed red meat consumption included "beef, pork, or lamb as main dish" (pork was queried separately beginning in 1990), "hamburger," and "beef, pork, or lamb as a sandwich or mixed dish." ... Processed red meat included "bacon" (2 slices, 13 g), "hot dogs" (one, 45 g), and "sausage, salami, bologna, and other processed red meats" (1 piece, 28 g).Notice that one of the foods listed under "unprocessed red meat" - and likely a major contributor to that category - is hamburger, the stuff fast-food dreams are made of. Although this study tracked whole grain intake, it didn't track refined grain intake, so we know right away we can't totally account for the white-flour buns wrapped around those burgers (or many of the other barely-qualifying-as-food components of a McDonald's meal). And unless these cohorts were chock full of folks who deliberately sought out decent organic meat, it's also worth noting that the unprocessed ground beef they were eating probably contained that delightful ammonia-treated pink slime that's had conventional meat consumers in an uproar lately.

Next, we arrive at this little gem:

The reproducibility and validity of these FFQs have been described in detail elsewhere.Ding ding, Important Thing alert! As anyone who's spent much time on earth should know, expecting people to be honest about what they eat is like expecting one of those "Lose 10 pounds of belly fat" banners to take you somewhere other than popup-ad purgatory: the idealism is sweet and all, but reality has other plans.

And so it is with food frequency questionnaires. Ever since these questionnaires were first birthed unto the world, scientists have lamented their most glaring flaw: people tend to report what they think they should be eating instead of what actually goes into their mouth. And that's on top of the fact that most folks can barely remember what they ate yesterday, much less what they've eaten over the past month or even the past year.

As a result, researchers compare the results of food frequency questionnaires with more accurate "diet records" - where folks meticulously weigh and record everything they eat for a straight week or two - to see how the data matches up. If we follow that last quote to the links it references, we end up at one of the validation reports for the food frequency questionnaire used with the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. Here's where it gets interesting:

Foods underestimated by the FFQs compared with the diet records (ie, the gold standard) included processed meats, eggs, butter, high-fat dairy products, mayonnaise and creamy salad dressings, refined grains, and sweets and desserts, whereas most of the vegetable and fruit groups, nuts, high-energy and low-energy drinks, and condiments were overestimated by the FFQs.This shouldn't come as a shocker if we consider human psychology. Unless we literally live in a cave, most of us are constantly inundated with messages about how high-fat dairy, meat, sweets, desserts, and anything delicious and creamy is going to either make us fat or give us a heart attack - while it's more like hallowed be thy name for fruits and veggies. Is it any wonder that folks tend to under-report their intake of "bad" foods and over-report their intake of the good ones? Who wants to admit - in the terrifying permanency of a food questionnaire - that yes, they do bury their salad in half a cup of Hidden Valley Ranch, and they do choose white bread because 12-Grain Oroweat tastes like lightly sweetened wood chippings, and sometimes they even go a full three days where their only vegetable is ketchup? If food frequency questionnaires were hooked up to a polygraph, we might see some much different data (and some mysteriously disappearing respondents).

Another reference in our study du jour takes us to a validation report for the Nurses' Health Study questionnaire. And here we find the same trend:

Mean daily amounts of each food calculated by the questionnaire and by the dietary record were also compared; the observed differences suggested that responses to the questionnaire tended to over-represent socially desirable foods.Of course, if everyone over-reported or under-reported their food intake with the same magnitude of inaccuracy, we could still find some reliable associations between food questionnaires and health outcomes. But it turns out that how much someone fudges their food reporting - especially for specific menu items - varies wildly based on their personal characteristics. Using an Aussie-modified version of the Nurses' Health Study questionnaire, a study from Australia measured how accurately people reported their food intake based on their gender, age, medical status, BMI, occupation, school-leaving age, and use of dietary supplements. Like with the other validation studies, it compared the results of the food frequency survey with the Almighty Weighed Food Record.

The surprising results? Folks with a "diagnosed medical condition" - including high cholesterol, high triglycerides, diabetes, high blood pressure, stroke, cancer, and heart disease - were much more likely to mis-report their meat consumption than folks without a diagnosed medical condition, generally overestimating their true intake on food frequency questionnaires compared to the weighed food record. Why this occurred is one of life's great mysteries, but it might have something to do with the fact that people who develop diet- and lifestyle-related diseases pay less conscious attention to what they eat. (In this study, women were also more likely to inaccurately report their intake for a wide variety of foods - a phenomenon that's been examined in greater depth by other researchers.)

So what does this mean for studies based on food frequency questionnaires, like the one currently hijacking the news outlets? Unfortunately for lovers of scientific accuracy, it means that meat consumption and modern diseases might be statistically more likely to show up hand-in-hand by mere fluke. If sick folks have a tendency - for whatever reason - to say they're eating more meat than they really are, that'll have profound effects on any diet-disease associations that turn up in observational studies, where correlations hinge so heavily on the accuracy of the data. And if the results of that Australian study are applicable not only in the Land Down Under but also in the Land Up Over, it could mean that meat is pretty much doomed to look guilty by association with disease whenever food frequency questionnaires are involved. Woe is meat!

Red-Meatophiles: A Species of Their Own

Now that our confidence in food frequency questionnaires should be thoroughly and disturbingly shattered, let's hop back to the study in question. To gauge the effects of red meat consumption on mortality, the researchers for our Red Meat Consumption and Mortality study divided folks up into five quintiles based on their red meat intake. The first quintile represents the people who reported the fewest servings per day, while the fifth quintile represents the shameless red-meat gluttons who indulged in the most (or rather, reported indulging in the most). Luckily for us, the researchers provided a magical table of marvels comparing various diet and lifestyle variables between the quintiles. Please take a minute to look at it yourself and, if you feel so compelled, bask in its glory.

If you secretly suspected that this was a "people who eat red meat do a lot of unhealthy things that make them die sooner" study, you can now gloat.

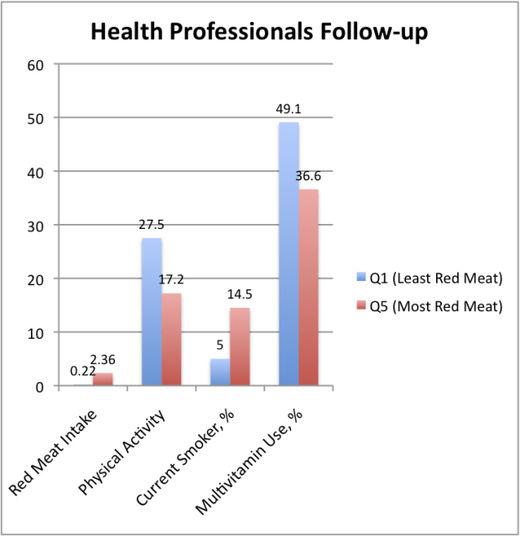

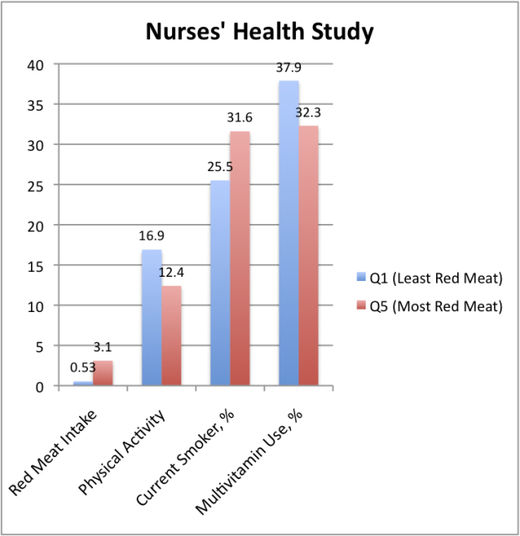

Here are a few lifestyle variables I graph-ified for greater visual impact. ("Red Meat Intake" is measured in servings per day, and "Physical Activity" is measured in hours of metabolic equivalent tasks.)

As you can see, the folks eating the most red meat were also the least physically active, the most likely to smoke, and the least likely to take a multivitamin (among many other things you can spot directly in the table, including higher BMIs, higher alcohol intake, and a trend towards less healthy non-red-meat food choices). Although the researchers tried their darnedest to adjust for these confounders, not even fancy-pants math tricks can compensate for the immeasurable details involved in unhealthy living, the tendency for folks to misreport their diet and exercise habits, and whatever mild insanity emerges from trying to remember every food that hit your tongue during the past year.

And in case you didn't spot them yet, our magical table has two particularly ogle-worthy things. The first one's this:

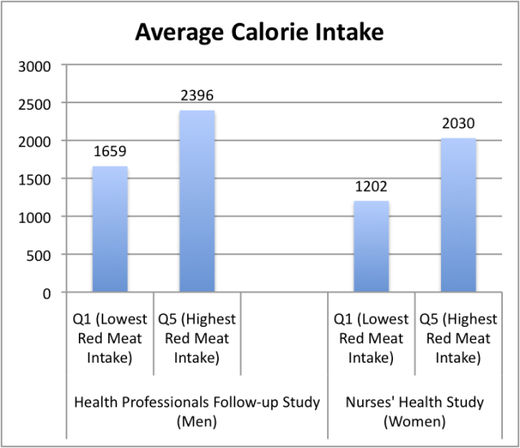

If you had any doubt that people fib on food questionnaires, this should put your mind at ease. Take a look at the average (reported) calorie intake for the women in the first quintile of red meat consumption. Yes, that does say "1200 calories." Yes, that is low enough to make most people wake themselves up at night as they unconsciously gnaw on their own arm in a quest for nourishment. And the red-meat-avoiding men aren't much better, clocking in at a bit over 1600 calories for fully-grown adults. If there really is an 800-calorie gap between the folks with the lowest and highest red meat consumption, there's obviously something much more significant going on in their diets than the color of their chosen animal foods. And if - in a much more likely scenario - there's some major mis-reporting going on, that only bolsters the notion that we shouldn't trust food frequency questionnaires any farther than we could throw 'em.

Here's the other ogle-worthy thing:

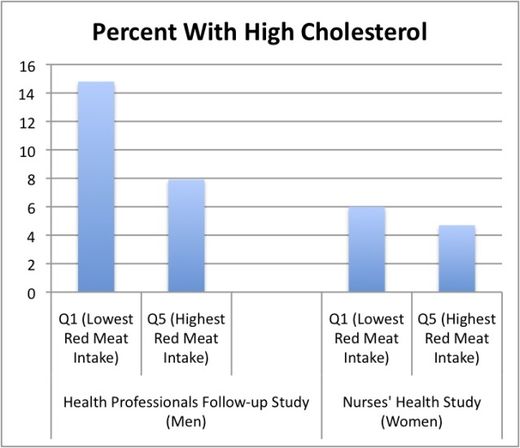

Ah, yes: here we see the folks eating the least red meat have the highest rates of elevated cholesterol, while the red-meat-indulgers have the lowest rates. Given the media's eagerness to assign cause and effect to this study, it's mighty strange none of the headlines proclaimed "Red meat reduces cholesterol!"

So What About This Death Stuff?

For those of you who hoped this analysis would completely obliterate any link the researchers found between red meat and "dying prematurely," here's the anticlimactic part. In the context of what's ultimately wobbly, imperfect, and tragically inconclusive observational data, the researchers did find that the folks reporting the highest intake of red meat had slightly elevated rates of death from cardiovascular disease, cancer, and total mortality (though as we should know by now, correlation isn't causation!). After adjusting for age and the other documented confounders, the association went down but didn't disappear completely. (If you like staring at numbers, you can take a gander at the tables for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease mortality, and cancer mortality to see how death risk changed between quartiles and with various statistical adjustments. And you can check out the lovely Zoe Harcombe's parsing of the study if you're craving an even geekier data safari.)

But there's still more to the story.

Those numbers thrown around in the fear-mongering news clips - 20% increased risk of death from all causes for processed meat and 13% increased risk of death from all causes for unprocessed meat - are classic examples of how even the most ho-hum findings can sound dramatic if you spin them the right way (and remember to attribute them to Hahhh-vard). If your risk of dying from a particular disease is 5% to start with, a "20% increased risk" only bumps you up to 6% in the grand scheme of things. That's a lot less scary. Especially when delectable foods are involved.

Lessons From the Past

In case you're skeptical that observational studies can run disturbingly contrary to reality, look no further than the hormone replacement therapy (HRT) craze that peaked a few decades ago. By 1991, 30 observational studies - including this one based on none other than the Nurses' Health data - collectively showed that women taking estrogen seemed to have a 44% reduction in heart disease risk compared to their non-hormone-replacing counterparts. Naturally, this led literally millions of women to jump on the estrogen bandwagon in pursuit of better health and longer lives. A very unfortunate oopsie-daisy sprouted up later when some randomized, controlled trials finally emerged and revealed that rather than being protective, hormone replacement therapy actually increased heart disease risk by 29%!

Just like we see with red-meat avoiders versus red-meat indulgers, these observational studies showed that women using hormone therapy generally had healthier lifestyles than women who weren't - including smoking less and exercising more. Their good lifestyle habits obscured the true effects of taking hormones, just as meat eaters' bad lifestyle habits might obscure the true effects of eating red meat. Are we sure that a similar risk ratio flip-flop wouldn't happen if we moved away from observational studies of meat consumption and towards infinitely more reliable randomized, controlled trials?

Until we actually have some studies like that, it'll be impossible to know - but if history has any say in the matter, it's a strong possibility. And while we patiently twiddle our thumbs waiting for those well-designed meat studies to start existing, we should keep in mind that humankind has survived a pretty doggone long time - in much more robust shape than most of us are today - without carefully swapping our lamb shanks for an equivalent serving of kidney beans.

Does Red Meat Make Bad Things Happen?

Since the very dawn of the taste bud, it seems red meat has been shrouded in mystique and evilness. Although the crumbling foundations of our anti-saturated-fat beliefs have partially redeemed meat and restored its throne on the dinner plate, red meat hasn't quite escaped the stigma of being bad, even if we can't totally pinpoint why. Is there a valid reason to avoid it?

Assuming you've nixed nitrite-laden processed meats and seek out higher-quality animal parts, one of the biggest legitimate dangers with red meat has more to do with preparation methods than the meat itself. High-temperature cooking - like pan-frying or grilling to the point of well-doneness - can create mutagens called heterocyclic amines (among other nefarious compounds) that may potentially contribute to cancer. Although the research here isn't totally conclusive yet, it's probably wise to stick with gentler cooking methods as often as possible (or better yet, learn to love steak tartare).

In Conclusion

Although the wildfire-esque media coverage of this study is enough to make any omnivore feel like punching Al Gore for ever inventing the internet, it's actually a great opportunity to test our critical thinking skills and explore the unending deficiencies of observational studies - including the self-reported data they're often built from. We might not emerge with any newfound health guidance after breaking down bad science, but it's always nice to have a better understanding of what the tumultuous world of research is really saying.

And with that, our latest installment of Science Says Meat Will Kill You has come to a close. But worry not: this is just the beginning of an exciting new season of food drama. Will the butter defeat the margarine in their upcoming oil-wrestling contest? Will the asparagus discover who really killed her uncle's stepdaughter's boyfriend's roommate's poodle's groomer? Tune in next week to find out!*

*Episode may or may not actually air

The basic principle of Christianity is in harmony with Vedic dharma in that the Bhagavad-gita teaches total surrender to the will of God as also does the Bible. But the devil is in the details. When the Christians try to justify meat eating by the invalid principle that the animals do not have souls, they are polluting the pure teachings of Christ with adharma or irreligion. The Bible teaches "Thou shalt not kill" while the Christians are murdering millions of innocent animals every day in their slaughterhouses.

If we are ever going to have a peaceful war-free, terror-free world, we must stop terrorizing the animals. As long as we torture and terrorize these innocent creatures we must accept the karmic reaction of ourselves being tortured and terrorized. Therefore it is absolutely required for world peace that every government throughout the world must now criminalize the slaughterhouses. The heinous, atrocious murder of the poor animals must immediately be stopped. If this is not done, what lies ahead for the sinful cow-killing civilization is indeed very dark and inauspicious. Therefore out of kindness upon our fellow human beings we must convince them to stop murdering the innocent animals.

[Link][Link]